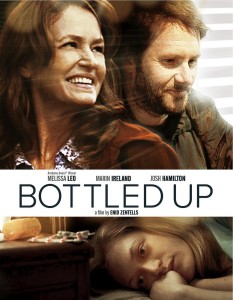

Indie directors love to mix genres in order to introduce us to fairly realistic characters, unusual stories and fresh narrative strategies. Enid Zentelis effectively mixes elements of serious drama, romantic comedy, and discomforting black comedic elements of the horror film in her low-budget gem, Bottled Up (2013), which is not only a “women’s picture,” but also an unusual working class women’s story of painkiller addiction meets sobering eco-horror film. It was made on a very small budget and few have seen the film. There are moments in Bottled Up that are excruciating and difficult to watch, yet there are moments of light romantic comedy amongst the horror.

This odd mix captures the absurdities of modern life more effectively than films with much bigger budgets. A great deal of the credit needs to go to Melissa Leo, whose acting ability is so rare and so immensely gifted that her mere presence in a film often elevates it beyond and above the material. Bottled Up is a strange brew and it doesn’t always work entirely, but when it does work it is thanks not only to Leo’s acting, but also to the smart directorial choices of Enid Zentelis, whose last directorial effort was another working-class drama, Evergreen (2004).

Like many films that center on women and don’t play by the rules, Bottled Up is hard to pigeonhole; most critics annoyingly dub it “quirky,” but there is a gritty realism about it that stays with you. Shot on a shoestring budget in upstate New York, I could say that this film provides yet another demanding and terrific role for Melissa Leo, but it is probably more accurate to say that she crafts the leading role here into a major career achievement.

I found Bottled Up hidden on pay-per-view (like so many good sleepers) and chose it because I saw Leo’s name in the credits. Also I like to check out low budget films that are obviously dumped by distributors as “not easily marketable.” American films that don’t get any distribution are often superb and memorable films, yet without any real advertising support and/or national distribution, they’re often passed over.

It is not unusual to see Melissa Leo in the role of desperate working class single woman, but she brings freshness to every performance. The working class women she creates are unique and don’t seem to be versions of Melissa Leo. She is one of the least lazy actors working, giving 150 % to projects big and small. Her knockout (often speechless) performance as a single mother forced by dire poverty into border smuggling in Courtney Hunt’s Frozen River (2008) demonstrates that she is a character actor who can do more than hold her own in the leading role.

Leo’s ability to bring to life the nuances and deeply human characteristics of so many different types of working class people is a testament to her apparent ability to understand the motivations behind the desperate and sometimes psychotic behavior of those who are the most oppressed by the class system; the women at the bottom rung of America’s anti-human capitalist machine.

The harrowing performance she turned in as a date-raping (sic) woman in a pick-up truck in the infamous and deeply unsettling episode of Louie (season 3, episode 2 [2012]) is a good case in point. It is not as if she had a great deal of time to develop her character, but in that performance she demonstrates how to go from a funny, “up for anything” drinking companion on a barstool to a hard bitten woman behind the wheel of a beat up pick up, a woman who suddenly seems more than a tad like the seriously damaged goods in Monster (2003), a truly frightening woman who can take out a large man both verbally and physically in an instant and reduce him to a shaking, terrified victim.

I cannot recall seeing any other female character suddenly overtake a man and smash his head into a car window after she has given him sexual pleasure – only to force him to give her oral sex. The Louie episode caused a great deal of controversy and online discussion, largely I think because many people don’t think women are capable of violence, which is both nonsense and based on sexist (Victorian) notions of women’s identity.

As many feminist critics argue, in order for women (and this goes for any minority) to be recognized as full human beings, we must go beyond representations that adhere to artificial binaries, with the good girl/ Victorian woman on a pedestal at one end and the abused victimized figure/loose woman on the other. You would not know it from looking at contemporary pop culture, but there is a whole wide spectrum of types of women in between these artificial binaries. Some of them are not so nice: some are even monsters. Whether or not they are monsters because of capitalism, patriarchy, and/ or genetic disorders is not at all cut and dried, as it is a culmination of factors that lead to personality disorders.

For example, Bottled Up gives us a glimpse of a junkie daughter who is both sweet, monstrous and acutely narcissistic and a mother who is at once sweet and caustic; likeable and unlikeable; a compulsively driven enabler of her drug addict daughter who behaves sometimes as if she herself may suffer from a personality disorder. These are believable women because they are multifaceted. They are beaten down by virtue of the class system, but they are human beings nonetheless who are worth taking the time to get to know. They are not disposable human beings, and films like Bottled Up remind us that stories of people who don’t have perfect teeth or cookie cutter cliché lives don’t deserve to be dumped on the rubbish pile, nor do films about them.

Misguided and antiquated psychoanalytic feminist thought is phallocentric and sexist, in that it insists that women are often victims defined by “lack,” (lacking a penis and lacking phallic power) and that any power women have is borrowed from patriarchal order, but this whole system is dependent upon a distorting phallocentric prism that goes back to Freud and Lacan, and has been entirely rethought by modern feminists who reject, for example, the essentialist notion of the “phallic woman” who must supposedly “borrow phallic power from patriarchy” to exert any power or authority. Women’s roles within patriarchy and capitalism are far more complex, especially with the rise of late stage capitalism wherein class struggle and the power of capital trumps even gender. Women are no longer defined by the binaries of dated psychoanalytic theories. Things are not obviously that simple in real life and it does not serve women to over-simplify us or victimize us.

In all her various roles, Melissa Leo carves out territory that demonstrates that not only are women all kinds of things (often all at once) and that many types go unrepresented in popular culture; but women are multi-faceted, and that is especially true of women at the bottom of the social order, the women who can barely make ends meet. In one woman you can find the archetypical behavior of the mother, the savior, the victim, the abuser and the lover; indeed these things often co-exist in one character, particularly if the actor is good enough to pull it off.

You find more complicated women in older classic films but they are a rarity in mainstream Hollywood fare. Only truly driven indie filmmakers who are willing to take risks make us continue to think about characters after we have seen a film and these filmmakers are generally marginalized: they just don’t fit in to the capitalist order, nor, often, do their characters.

One of the great pleasures of watching a performance by Melissa Leo is watching her expand her own range as a fearless actress who helps directors relate stories of the types of women whose stories often don’t get told – average women, imperfect women, poor women, older women, angry women, crazy women, sexy women, isolated women, women who are not dazzlingly attractive or Hollywood “types.” Leo brings these aspects of all types of women to life in her characterizations in a way that we have rarely seen since the days of Barbara Stanwyck, who could herself bring just about any written character to life, no matter how well written or even ridiculously written.

One of the great pleasures of watching a performance by Melissa Leo is watching her expand her own range as a fearless actress who helps directors relate stories of the types of women whose stories often don’t get told – average women, imperfect women, poor women, older women, angry women, crazy women, sexy women, isolated women, women who are not dazzlingly attractive or Hollywood “types.” Leo brings these aspects of all types of women to life in her characterizations in a way that we have rarely seen since the days of Barbara Stanwyck, who could herself bring just about any written character to life, no matter how well written or even ridiculously written.

Leo often plays complex yet relatable working class women; she hints at what drives these women just enough that most of us “get it” without having to be hit over the head with unnecessary back-story or excess explanation. If you have experienced the joys and frustrations of being a working class white woman, Leo speaks both to and for women in ways that are quite extraordinary and fairly uncommon. Leo understands that action is character, and she seeks out directors who feel similarly. Through actions, Leo builds deep characterizations that avoid simplistic over-determination and essentialism as they avoid the dull binaries of old gender conventions. Leo redefines white working class women as very complex beings.

In Bottled Up, Leo plays Fay, a desperate but functional single mother and small business owner who runs a small town mailing facility with several humorous sidelines, including body piercing. It is the kind of place that you find just barely holding on in small town America during these hard times. Fay is middle aged and pretty, but for the majority of the film she hides herself beneath a mop of bangs that covers the top of her face. The bangs are so long that it is more than a little distracting, but they also have the effect of drawing you in to Fay and make you want to know her better.

In Bottled Up, Leo plays Fay, a desperate but functional single mother and small business owner who runs a small town mailing facility with several humorous sidelines, including body piercing. It is the kind of place that you find just barely holding on in small town America during these hard times. Fay is middle aged and pretty, but for the majority of the film she hides herself beneath a mop of bangs that covers the top of her face. The bangs are so long that it is more than a little distracting, but they also have the effect of drawing you in to Fay and make you want to know her better.

You literally want to push aside those bangs and see what Leo is up to with her deeply expressive eyes. We don’t have to be told that her character has seen too much of life and she has worked very hard to put together a hardscrabble existence. She is proud of her small barely hanging on business; she maintains her tiny home and brings life to her surroundings; she tries very hard to put on a brave face to meet the days, but we can see that it takes almost all her remaining resolve and effort. We don’t hear too much backstory, but we know it has not been an easy life. Fay seems to have long withdrawn and mostly given up on people; but she gives a great deal of love to her plants.

Things start to make sense when we meet Fay’s grown daughter, Sylvie (Marin Ireland) who is both a sweet perpetual adolescent and a frightening and erratically behaved prescription drug addict who will do anything to get more medication. We quickly come to understand Fay’s role as full time enabler of Sylvie’s addiction.

Codependency is an ugly thing to witness, and addiction itself is like a terrifying creature who lives in their small home in the woods near the river; it simply will not leave and hangs over everything like one of the angry ghosts we meet in Japanese horror films. Pain and addiction terrorize these two women on a daily basis. Fay blames herself for her Sylvie’s addiction because she was behind the wheel in an accident that left her daughter with back pain that led to abusing painkillers long ago.

Fay has so much empathy for her child and so much excess guilt that she cannot stop helping her daughter get drugs, even if she understands, at some level, that this behavior has gone on long enough and her daughter needs an intervention. Some of the most excruciating scenes involve the two trying to get meds or fighting with one another. Some scenes are funny, some are tragic but many mix these feelings as they are mixed in real life.

This odd mixture is probably what limits the box office, but it is the very thing that makes the film worth watching. There are terrifying and awkward visits to doctor’s offices, so much pleading and lying to get meds and the home has about as much peace as a home in a horror film. Leo excels in these scenes, largely hiding her expressive eyes from us under those bangs, but we often glimpse her face contorting in pain or anger, or she uses gesture or her tone of voice to show how utterly desperate and alone she feels.

Things get even weirder (truly scary and, oddly, more romantic) when Fay meets a younger man named Becket (Josh Hamilton), a misguided dreamer who is trying to run away from his past and become an environmentalist. Becket is a sweet well-meaning guy, but a bit of an idiot, more than a little clueless, especially when Fay moves him into the house as a boarder.

Fay very much hopes that he will fall for her daughter. It is not clear, but it seems that she may be deluded or desperate enough to see in Becket a possible savior for Sylvie, or maybe she just thinks, in desperation, that the arrival of a stranger in the hellish home will make some sort of change in their house of misery and drug dependency.

Fay clings to the idea that she has some sort of control over her adult child, but we rapidly learn that she has no such control. She carefully doles out the meds and tries to exert authority over an addict, and we all know this never works. Sylvie is abusive; she is prone to dramatic fits and screaming matches with her mother, whom she manipulates and tries to outwit to get more and more prescription meds.

Prescription med dependency and abuse goes on in millions of homes, but it is usually treated in popular culture as an aberration and it carries a huge stigma that silences any real discussion of drug addiction or pain management. Doctors can be callous and send druggies out of their office with disgust, treatment facilities are expensive. Fay will do anything to get her daughter drugs, including faking a shoulder injury herself.

Societal attitudes and the medical industry, as the film demonstrates, turn Fay into a criminal accomplice rather than offer any help. Help is for the wealthy. Fay is desperate, but her witty remarks and unaffected nature attract the young eco-minded Becket. Becket stumbles into this dysfunctional family (is there any other type of family?) and tries to woo Melissa Leo and it is sometimes painful to watch, sometimes very sweet and always very awkward.

When Becket is brought into the home, he brings with him his newfound stringent eco-rules and both Fay and Sylvie try to recycle and eat vegan food, and these scenes are oddly humorous and light, but the ghost of addiction hangs over everything in the house, except maybe Fay’s plants that she so carefully tends. When the women bring Becket into their home as a boarder, it feels very dangerous indeed. In fact, as a viewer you wonder just where the film is going. Is it venturing toward the territory of Don Siegel’s The Beguiled (1971)? No, but things get very frightening indeed, because Becket is so clueless about Sylvie’s drug abuse. He is absolutely smitten with Fay, and thus effectively blinded by love.

When Becket is brought into the home, he brings with him his newfound stringent eco-rules and both Fay and Sylvie try to recycle and eat vegan food, and these scenes are oddly humorous and light, but the ghost of addiction hangs over everything in the house, except maybe Fay’s plants that she so carefully tends. When the women bring Becket into their home as a boarder, it feels very dangerous indeed. In fact, as a viewer you wonder just where the film is going. Is it venturing toward the territory of Don Siegel’s The Beguiled (1971)? No, but things get very frightening indeed, because Becket is so clueless about Sylvie’s drug abuse. He is absolutely smitten with Fay, and thus effectively blinded by love.

Fay, in turn, enjoys the young man’s attentions, and she blossoms and starts to pull the hair out of her eyes, even as she makes every effort to shove Becket toward her daughter as a romantic prospect. Not too long after he moves in, Sylvie overdoses on pills, and Becket and Fay find her near death in the bathtub. The scenes of Fay and Becket trying to bring her back from the brink of death by walking her around the room are chilling and uncomfortably humorous. Sylvie is clearly near death, and Becket has no idea what is happening. It is bad enough that Fay will not allow Becket to call the police in her attempt to cover up her daughter’s addiction, but she also lies and tries to pass off Sylvie’s illness as a form of epilepsy.

These scenes really allow for Leo to shine as she desperately moves between flirting and lying and turning into a manipulative co-dependent crazy mother trying to protect her daughter, with whom she is furious. Despite the addiction that rules the home, Fay more or less keeps things together for a time and the three manage to eat a few meals together and form a sort of mock normalcy. Fay is even successful at getting Sylvie romantically interested in Becket, but the moment she turns her back, Sylvie is getting into more trouble with drug dealers and Becket has zero romantic interest in Fay’s “epileptic” kid.

In between scenes of domestic semi-tranquility and meals shared together, there is a rather horrifying moment outside in the garden. Fay leaves her daughter for a moment with Becket and Sylvie suddenly takes a hammer and purposefully slams it into Becket’s hand, injuring him very badly, but Sylvie passes this vicious and cruel act off as a gardening mishap. You realize that she’d kill him, or anyone, for meds.

Becket suspects there is something very wrong in the house, but he is much more concerned with the environment, and he takes samples from the nearby river to check them for pollution. He also drags Fay and Sylvie to small, poorly attended, poorly organized protests against fracking and other types of pollution. He is a little lost, but he has an open heart and he takes on too many causes.

Becket is a lonely young man and he is so smitten with Fay that she doesn’t really take his flirtations that seriously until he kisses her and they make love very sweetly. Even after they make love, Fay thinks he is too young for her and she tries to put an end to their relationship, but he insists that he is her boyfriend.

Things get very, very harrowing, however, when the daughter manipulates Becket into a drive up to Canada. He has no idea that the real reason they are going to Canada is to purchase medication and smuggle it across the border. Fay is considering telling him. She is not going to allow her daughter to destroy him or herself.

Leo’s face goes into several contortions during this time; she is thinking about how to get out of this life that she has been holding together so desperately; she is experiencing the joys of being in love for the first time in a very long time; and she is so very angry and frustrated with her daughter, yet she loves her and continues to lie for her. There is so much going on in Leo’s face and gestures that it may as well be a silent film: watching Leo take this role and turn it into a real life woman is pure cinematic pleasure.

Though many argue that Bottled Up is marred by an unrealistic happy ending, it provides a fairy tale ending of sorts, in that the older woman, after suffering the tortures of the damned trying to parent a junkie, finds love in the arms of the younger man, but that is only a small part of the story as Zentelis tells it. There are really a couple of endings to the film, but the most memorable one is at the border at customs in Canada when Fay pulls the plug on her daughter and puts an end to the bottled up emotions and denial that have plagued this family for too long.

The unrelenting psychological pain and grim determination that Leo summons in order to stop her daughter from planting drugs on the innocent Becket is truly heart rending. Leo captures a mother who is going through the tortures of the damned as she stares at Becket’s backpack where Sylvie has placed the drugs and contemplates a last minute plan, a plan that means she will turn her daughter over to the authorities.

At the Canadian border, as they wait in a car in the line for customs, Fay deliberately calls attention to their car in order to get them caught and she quickly places the evidence in her daughter’s bag, thus ending her isolation and hellish existence through tough love, so to speak. It is tragic but necessary.

If you have been keeping an eye on Leo, she has been tortured during the entire trip, her face in the car as they drive around Canada looking for prescription meds is indeed the face of a mother going through a moral hell and her dissolution of the dysfunctional aspects of the family is a happy-ish ending, as is her unlikely pairing with the hesitant shy young budding environmentalist. Those who enjoy a good romance will perhaps be unsatisfied because the end is more than a little bittersweet and certainly not a Hollywood fairy tale ending. We all know that reformed junkies have a habit of reverting back to their addictive behavior.

If you have been keeping an eye on Leo, she has been tortured during the entire trip, her face in the car as they drive around Canada looking for prescription meds is indeed the face of a mother going through a moral hell and her dissolution of the dysfunctional aspects of the family is a happy-ish ending, as is her unlikely pairing with the hesitant shy young budding environmentalist. Those who enjoy a good romance will perhaps be unsatisfied because the end is more than a little bittersweet and certainly not a Hollywood fairy tale ending. We all know that reformed junkies have a habit of reverting back to their addictive behavior.

The critics who call Bottled Up “a quirky light romantic comedy” seem to completely miss the more harrowing aspects of the film. Lost a bit in the narrative is the story of the aspiring environmentalist, but that is a choice that Zentelis specifically made – because she wanted to show that in the end, environmentalism is often for the privileged because it is much too difficult for the working class to simply survive, much less take up social causes.

I take it as a given that Fay, Sylvie and Becket will further pursue social activism as a patched up family after the credits, and their lives will continue to be complex and difficult, as they navigate the treacherous terrain of poverty, family, and love.

Gwendolyn Audrey Foster frequently writes for Film International. She enjoys tracking down overlooked indie films and sleepers that fall under the radar, especially those that center around women and the working class.

Excellent review, Gwendolyn! I have been searching for articles about ‘Bottled Up’ to hear what others thought of it. I was stunned with the deep grit and complexity of Melissa Leo’s character as well. This film is a must-see!

Thanks Annie Marie!

It is not a great masterwork of the cinema, but a good little indie that takes chances and is not quite as formulaic as the usual fare. There are quite a lot of these little sleepers out there that get lousy distribution or no distribution.

To tell you the truth, I’d tune in to watch Melissa Leo read a phone book, I like her work THAT much! She is terrific as usual and makes every project better that she is in!

Cheers;

Gwendolyn

I think that we have seen many examinations of addiction in film yet what appealed to me about this effort was looking from another angle. The co-dependency was brutal and Melissa Leo – as you’ve said, it incredibly talented – she did not disappoint in this film.

Thank you for the great information about this film story! I think is interest in the mix of romance plus comedy horror.

Mellisa Leo in the Fighter was spectacular; this woman uplifts every movie she stars in. Bottled Up is quite a remarkable indie, which easily goes from extreme laughter to dark scenes. I’m big on movies that show versatility and don’t focus only on the grim aspect of life.

Mellisa was extraordinary as Fay and her first-class acting and personality helped this movie a lot. Her drug addict daughter behavior is mostly enforced by Fay and both share a destructive behavior that is painfully to watch.

If you love indie movies and aren’t big on seeing big shot actors on screen, give Bottled Up a try, chances are you will like it.

Thanks Gwendolyn for this exhaustively review.

I agree, Louisa and Clint, and thanks for your comments.

I came across an interview with Enid Zentelis and she said that one of the reasons she made this film is that there are so many films about addicts, but not too many films about enablers and enabling behaviors. Zentelis also talks a bit about how being a mother makes being a caregiver/enabler even more complicated. I find her take on addiction and enabling very powerful. A film such as this would never be made by the studios these days. TV treatments of addiction (numerous “recovery” shows) make the addict go through a sort of exploitational show trial, not unlike a freak show.

It is really hard to capture the codependent nature of the enabler/ addict relationship, because the addict is truly in pain and the enabler feels anxious to stop the pain– even when they know there is addiction that must end. An enabler is often isolated by social stigma.

Society treats the addict like a freak but never asks why people get addicted in the first place. Society is in such extensive denial about things like pain, enabling, and addiction and these things are still today treated as if they are outside the norm. They are the norm, in my opinion and I appreciate that Zentelis makes this point clear too.

I recently gave ‘Bottled Up’ a second viewing, and couldn’t help coming back to this article. I’m more mesmerized than ever with Melissa Leo’s role here. As you said, Gwendolyn, it’s not a masterpiece of cinema, but it certainly is a thought-provoking performance.

BOTTLED UP is a film that oddly sticks with you. I have friends who are addicted to prescription drugs, but they would never agree that they have a problem at all. I have major issues with the casual way doctors hand out prescriptions to adults and even to my students. Nobody sits down to talk with people with problems, they just whip put the prescription pad – it seems to me.

Talk therapy seems to be a thing of the past, sadly.

This can really make relationships very difficult, even if we are not living with addicts that skate under the radar. You never know who you are talking to, really, because personalities change so much when they take these drugs. So many people I know are really changed by completely changed by legal pharmaceuticals that are prescribed like candy. They are often completely unaware of how these drugs have changed them. It is perhaps not always as acute as it is displayed in this film, but not to be able to say anything about it makes one feel a bit like an enabler. Few people even talk openly about these things.

BOTTLED UP is an important film and Leo is magnificent.

Thanks for writing in, Annie Marie!

My wife made me watch this when it came out. I thought it would just be another boring movie but I actually ended up really liking it. Probably because of the comedy.