by John Andrew Gallagher.

Tay Garnett and and writer Howard Higgin spent the months of February and March, 1930 on Catalina Island writing Her Man, sharing a house with Lewis Milestone, who was working on the script of All Quiet on the Western Front with George Cukor, George Abbott, Del Henderson, and Maxwell Anderson. The Garnett-Higgin script was a comedy-drama with characters inspired by the ribald folk ballad “Frankie and Johnnie.” Their story had little to do with the song, though they took their title from it, and the theme is heard throughout the film and sets the tone for the picture:

Frankie and Johnnie were lovers

Oh, my Lord, how did they love!

They swore to be true to each other,

Just as true as the stars up above.

He was her man, but he done her wrong.

Frankie, I ain’t gonna tell you no story,

Us bartender men never lie.

That punk was here an hour ago

With a gal named Nelly Bly.

Frankie threw back her kimono

And took out her little .44.

Bang! went Johnnie to the land of Nevermore!

Garnett and Higgin set the story in a dancehall where singer Frankie fleeces the male patrons under the watchful eyes of Johnnie, “her man,” a thinly disguised pimp, and Annie, an old souse with a heart of gold. Dan, a sailor, wants to take Frankie away from her sordid life, and battles Johnnie for her hand. The writers delivered a 52-page story treatment loaded with dialogue on February 26, 1930, with the film set as a turn-of-the-century period piece on San Francisco’s Barbary Coast. The first draft screenplay by Garnett and Tom Buckingham was ready on April 5th under the title Frankie and Johnnie.

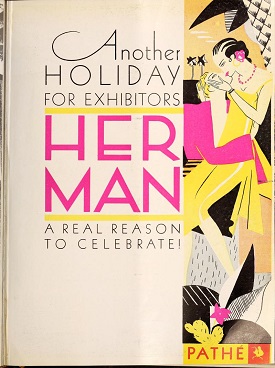

The new president of Pathe, E. B. Derr, was committed to raising the company to major studio status, and in February, 1930 announced an ambitious slate of 30 “specials,” no programmers, 52 two-reel comedies, 450 shorts, plus the Pathe News and Sportlights newsreels and Aesop’s Fables cartoons. In his effort to make Pathe a contender, he approved a budget of $371,560 for Her Man, with Garnett’s writer-director salary raised to $27,150.

Meanwhile, the Association of Motion Picture Producers (AMPP) was up in arms about the project. These industry watchdogs, headed by Will Hays, administered the Production Code and were immediately put on alert when they learned Pathe was planning something called Frankie and Johnnie. The play of the same name had been a cause celebre for many years and was frequently closed down by police for its bawdiness. The day after Garnett and Higgin submitted their first treatment, Pathe sent a copy to the AMPP’s Colonel Jason Joy, the overseer in the Hollywood Hays Office, to discuss possible censorship, and a month later the AMPP responded with objections to the prostitution, drinking, stealing, and fighting in the story. When Garnett sent the script to Colonel Joy on April 9th, there were even more violations of the Production Code. The period had been updated to the present, the locale had been changed from the Barbary Coast to Havana, the dance hall was obviously a home to hookers, and Frankie and Johnnie were clearly presented as prostitute and pimp. There was an over emphasis on liquor, disrespect for the Cuban police, an unfavorable depiction of Havana, a graphic scene of Johnnie’s murder, and a cast of characters that was almost exclusively limited to prostitutes, pickpockets, bums, hoods, and bartenders.

Meanwhile, the Association of Motion Picture Producers (AMPP) was up in arms about the project. These industry watchdogs, headed by Will Hays, administered the Production Code and were immediately put on alert when they learned Pathe was planning something called Frankie and Johnnie. The play of the same name had been a cause celebre for many years and was frequently closed down by police for its bawdiness. The day after Garnett and Higgin submitted their first treatment, Pathe sent a copy to the AMPP’s Colonel Jason Joy, the overseer in the Hollywood Hays Office, to discuss possible censorship, and a month later the AMPP responded with objections to the prostitution, drinking, stealing, and fighting in the story. When Garnett sent the script to Colonel Joy on April 9th, there were even more violations of the Production Code. The period had been updated to the present, the locale had been changed from the Barbary Coast to Havana, the dance hall was obviously a home to hookers, and Frankie and Johnnie were clearly presented as prostitute and pimp. There was an over emphasis on liquor, disrespect for the Cuban police, an unfavorable depiction of Havana, a graphic scene of Johnnie’s murder, and a cast of characters that was almost exclusively limited to prostitutes, pickpockets, bums, hoods, and bartenders.

The final draft was completed on May 1st and submitted to the AMPP the next day. Garnett and Buckingham had set the film in an nonspecific location, the cops were treated with more respect, and most importantly, the Frankie and Johnnie relationship had changed; Frankie was shown as being defiant towards Johnnie, wanting to free herself from his clutches. The murder of Johnnie was also altered. In this draft, Johnnie hurls a knife at Dan which sticks in the door and goes through the other side. When Johnnie and Dan fight on one side of the door, Dan knocks Johnnie backward and he is thrown up against the knife blade and killed (a similar bit of business was used by William Wellman in his 1932 The Hatchet Man). Garnett and Buckingham stayed in close consultation with Col. Joy, but on May 7th, Pathe received word that the script still did not satisfy the standards of the Code. They were unhappy with the Frankie-Johnnie relationship, feeling it was still an association of prostitute and pimp; Frankie’s pickpocketing attempts were deemed inconsistent with her desire to change; and there was a further objection to a brutal killing of Red, a rival of Johnnie’s.

Garnett wrote to Col. Joy’s superior at the AMPP, John V. Wilson, on May 9th, itemizing each complaint. Joy had indicated to Garnett that he’d be safe with the prostitute/pimp implication as long as he didn’t indicate Frankie and Johnnie were living together, and referred him to a scene in which Frankie unlocks the door to her flat with her own key, followed inside by Johnnie, who doesn’t even remove his hat. Garnett reasoned that Frankie’s frequent pickpocketing attempts were necessary to show her wrong in order to regenerate her. And lastly, he remarked that Joy had said Red’s killing would not be objectionable if at some point in the picture Johnnie atones for it, and his atonement is complete when he dies on his own knife. Garnett emphasized that the May 1st script had been written as a result of his conversations with Joy: “We have felt all along that the feeling of moral uplift and regeneration was so apparent that any objection to the manner of telling would be minimized by the unmistakable moral tone of the entire story” (1).

Several days later, Garnett spoke on the phone at length to Wilson, promising that care would be taken to bring out the fact that Frankie is not a prostitute but is mainly influenced by Johnnie because of her dependence on him for protection, essentially presenting her as a victim of circumstance with Dan saving her from such a life. The conversation appeased the AMPP, and Garnett was able to get back to his pre-production chores. The AMPP would wait for final judgement until the film was completed.

Ricardo Cortez was set for the role of Johnnie; the film marked something of a comeback for this once popular silent screen Latin lover (born Jacob Krantz in New York City), best known as Garbo’s first Hollywood leading man in The Torrent (1926). Russell Gleason, Walter Abel, George Brent, Russell Hardie, Dean Jagger, and James Murray (star of King Vidor’s The Crowd) were tested for the part of Dan, but the director had a hard time finding his romantic leading man. In Hollywood Filmograph (June 14, 1930), Garnett noted,

My new production, Her Man, now in the making, has given me no little worry from the casting angle. We made tests of every young leading man I can think of for my hero. Can you suggest one with a light in his eyes that would make a girl, reared in the atmosphere of ill-repute, think there really was something worthwhile in life? (2)

The role went to Phillips Holmes, borrowed from Paramount, who had just co-starred with Gary Cooper in Only the Brave (1930) (3). Pathe contract player Helen Twelvetrees was cast as Frankie (4) and former Broadway star Marjorie Rambeau, out of pictures since 1926, awarded the role of Annie, a part originally written for Marie Dressler. Garnett filled out the cast with a strong ensemble of character players, including James Gleason, Franklin Pangborn, Sennett comedian Harry Sweet, sexy Thelma Todd (in a black wig instead of her usual blonde locks), and Mike Donlin, former star centerfielder for the New York Giants and St. Louis Cardinals. Rehearsals began on May 29th, 1930 at the Pathe Studios and shooting started on June 4th with Edward Snyder as cameraman.

Before principal photography began, Garnett helped out Patsy Ruth, who hosted an episode of the popular short film series Screen Snapshots. In the one-reeler, he presents her with a “get-there-in-a-hurry machine” of his own design, a gag enabling director Ralph Staub to jump from interview to interview. This edition featured Samuel Goldwyn, promoting his new and upcoming fare with contract stars Ronald Colman (Raffles), Eddie Cantor (Whoopee!) and Evelyn Laye (One Heavenly Night).

Before principal photography began, Garnett helped out Patsy Ruth, who hosted an episode of the popular short film series Screen Snapshots. In the one-reeler, he presents her with a “get-there-in-a-hurry machine” of his own design, a gag enabling director Ralph Staub to jump from interview to interview. This edition featured Samuel Goldwyn, promoting his new and upcoming fare with contract stars Ronald Colman (Raffles), Eddie Cantor (Whoopee!) and Evelyn Laye (One Heavenly Night).

Her Man opens with the sound of the ocean and the roaring surf. The camera pans a rocky coast, then dissolves to the main titles written in the sand, waves rolling in to wash away each credit. The film proper begins on a crowded American dock as passengers disembark from an ocean liner. Garnett quickly throws in a gag – an overenthusiastic man on board ship waves to his wife on shore, pointing to his suitcase full of souvenirs, then inadvertently drops it into the water.

As a jazzy version of “There’s No Place Like Home” plays, we meet Annie (Marjorie Rambeau) coming down the ramp onto shore, a worn-out middle-aged floozie “from the wrong side of the island.” No sooner does she set foot on shore than Annie is stopped by the authorities – they don’t want “her kind” in port and put her on the next boat back to Havana, Cuba.

A closeup of Annie’s feet on deck, then a cop makes her move along. A long shot shows the ship passing the Morro Castle into Havana’s harbor, as the music segues into a Spanish theme. Garnett returns to a closeup of her feet, this time shuffling down the plank, dissolving to a closeup of her feet walking down the street. In the first of many extended takes, this one from a high angle, Annie walks down a seedy street in Havana’s red light district. It is a remarkable set, built by art director Carroll Clark entirely indoors on Pathe’s largest sound stage; the largest set on the Culver City lot, in fact, since DeMille’s The King of Kings (1927). Additional generators were required to light the set, with over 500 lamps from baby spots to sun-arcs.

Annie enters the Thalia Cafe, the setting for much of Her Man, moving through dancers to the bar (5). The younger girls taunt her, but Frankie (Helen Twelvetrees) takes pity on Annie and gives her money. Frankie is the heroine of Her Man, beautiful but bad. Raised in a saloon, a victim of her environment, Frankie never knew her parents, only “sneakin’, cheatin’, stealin’.” At the Thalia she entices sailors to dance (“How ’bout you and me shakin’ a hoof, good lookin’?”), then picks their pockets.

The pickpocket routine is a thin disguise for prostitution; despite the AMPP, she is obviously a hooker and slick Johnnie (Ricardo Cortez) is obviously her pimp. She is approached by Red (Mathew Betz), who wants her to join him. Johnnie overhears Red’s pitch to Frankie and has his hoods start a brawl in the saloon. While the fight provides a diversion, Johnnie pulls his knife and hurls it with deadly accuracy at Red. Like the murder of the barker in The Spieler(1928), Garnett stages an ominous murder amid the seeming safety of a crowd.

When the place settles down, Johnnie and Frankie leave. In a long track down the street, she must walk a full pace behind “her man.” In her room, Johnnie demands Frankie’s earnings for the night, then upbraids her for giving five dollars to Annie. Garnett has quickly established the seedy milieu of Her Man, the low-life hoods and whores, the drunks and dregs, prostitution, immorality, and murder. Typically, he gives Frankie a note of compassion in her concern for the pathetic Annie, who has become a perverse maternal figure for her, and a foreshadowing of what Frankie will become once her looks fade.

The next scene introduces Garnett’s Three Musketeers – Dan (Phillips Holmes), Steve (James Gleason), and Eddie (Harry Sweet), with the trio singing a novelty song “Far Far Away,” co-written by the director and George Green. Gleason and Sweet try to quench their unquenchable thirsts, while Dan finds himself immediately attracted to Frankie. She rhapsodizes to Dan about “places that are good and green, with trees,” then he catches her with her hand in his pocket and realizes her game. Despite the scam, Dan begins looking out for Frankie, while Johnnie is out two-timing with call girl Nelly Bly (Thelma Todd).

Garnett alternates Dan and Frankie’s developing romance with a great deal of comedy relief supplied by Gleason and Sweet in two recurring gags. In the first, Gleason keeps playing the slot machines to no avail, but Sweet hits the jackpot every time. The other centers around dandy Franklin Pangborn’s bowler hat. The usually effeminate Pangborn, in an atypical role as a sporty tough guy, brawls with Gleason and Sweet, is knocked out, and has his hat appropriated by the pair, who spend the rest of the picture fighting over it. Several times later in the film, Pangborn shows up to reclaim his hat, always with disastrous results.

Dan meanwhile is determined to get Frankie out of the seamy dive. “Sure, you’re all right,” he tells her. “You just got yourself figured wrong, that’s all. You been figurin’ you was a bad baby. You ain’t. You’re just a dame, and a pretty regular little dame at that. Why, you’ve been figurin’ you was hard as nails. You ain’t. You’re soft. Why, the reason you’ve been sayin’ that spiel of yours so good is way down deep inside you really mean it. You know you don’t belong here. And now you’re all burned up cause I’m wise to ya. Do I pick up the marbles now, sister?”

Frankie realizes that her only escape, her only redemption, is her love for Dan. But gin-soaked Annie warns her: “It ain’t in the cards, baby. Now don’t go fallin’ for no sailor. They ain’t none of ’em on the level with the dames they meet down here.” The voice of experience guzzles her gin.

Dan tells his mates that he won’t be sailing with them on the Peter Helms bound for San Francisco. Gleason, drunk and disbelieving, puts his beer mug under his nose, tips it to drink, and spills it down his shirt. “There’s an octoroon in the kindling somewhere,” he slurs.

Dan tells his mates that he won’t be sailing with them on the Peter Helms bound for San Francisco. Gleason, drunk and disbelieving, puts his beer mug under his nose, tips it to drink, and spills it down his shirt. “There’s an octoroon in the kindling somewhere,” he slurs.

On the fog-drenched Havana street set, the three pals stumble on their way. Frankie watches them leave and thinks Dan has left her forever. The next day, the Peter Helms sails off (though Steve and Eddie have been thrown in jail on a drunk and disorderly). The camera pulls back from the ship to reveal Frankie standing on the deck. She turns to go, and Dan is right there with her.

The reconciled couple ride in a buggy against a rear screen projection of Havana location shots. Frankie grew up never knowing her birthdate, so Dan gives her that day’s – March 17th, St. Patrick’s Day. To complete her spiritual transformation, Dan takes her to church. Kneeling at the altar, Dan genuflects, and Frankie awkwardly imitates him. Later, on a rear screen projection beach, “DAN” and “FRANKIE” are written in the sand (like the main titles), centered in a heart. The camera tracks along the shore following their footprints, and dissolves to a closeup of the buggy wheel. They plan to meet in an hour at the Thalia, then get passage to the States. But first, says Frankie, she has something to square….

At the Thalia, Annie tips off Frankie that Johnnie and his henchmen are plotting Dan’s murder, the same way he did with Red. The inevitable confrontation between Dan and Johnnie results in a spectacular climactic barroom fight, one of the most dynamic scenes in all of Garnett’s films. Paramount opened The Spoilers in New York on September 19, 1930; when Her Man followed on Broadway a month later, it surpassed even that film’s much-heralded donnybrook. Dan’s sailor friends storm the Thalia to fight Johnnie’s mob, and bodies fly about the room, crashing into tables, with the fighters using beer mugs, whiskey bottles, chairs and tables; indeed, the fight in Her Man looks almost too real. Garnett recruited a group of USC football players for the scene, including George Dye (center), Dink Templeton (running guard), Bill Armstead (star tackle), and Bill Emmons (regular end), as well as amateur weight-lifting champion George Taylor, bantamweight champ Frankie Dolan, and ex-pro fighters Mexican Joe Rivers, Jack Silver, Abe Attell, and Sailor Billy Vincent (who had played one of Red’s gang in The Spieler). The director pitted the footballers against professional stunt men, as he explained in 1973:

For that battle sequence we had two tents set up on the stage with cots in them – hospital cots – and two nurses and a doctor in attendance all the time because guys were getting constantly getting hurt – mostly the footballers. Usually they get hurt because they won’t listen or wouldn’t do what you ask them to do. It’s a strange thing about picture fights and picture action. The incidents in which men are actually injured are usually not as photogenic as a faked piece of action. (6)

The scene also brings to a head the two running gags. Pangborn shows up to get his bowler hat back after Gleason and Sweet have framed him into a jail stay, and Gleason, knocked out, lands at the slot machine and unconsciously hits the jackpot. Garnett uses the knife-in-the-door bit, with Johnnie landing on his own knife. The blade in his back, Johnnie straightens his tie, smiles, and falls to the floor dead, leaving Frankie and Dan to live happily ever after.

Garnett completed shooting on July 9, 1930 (a full week over schedule), and was presented with the gift of a mantle clock by the crew, while the film was assembled by editor Joseph Kane (later a director of B-Westerns, mostly for Republic Pictures) and assistant editor Pandro S. Berman (later an executive at RKO and producer at MGM, where he worked with Garnett on Soldiers Three).

Pathe had high hopes for Her Man, expecting it to equal the success of their Oscar-nominated romantic comedy hit Holiday (1930), directed by Edward Griffith and starring Ann Harding. Garnett was granted the rare privilege of filming a week of backgrounds in Cuba; in mid-July, he chartered a tri-motored plane, and with cinematographer Edward Snyder, made shots of Havana’s waterfront and harbor to be used in rear projection at the studio. The cost of the trip was shared by MGM, who needed Cuban backgrounds for their upcoming production of Woody Van Dyke’s The Cuban Love Song (1931). Some of the stock shots later appeared in RKO’s Suicide Fleet (1931) and Ann Vickers (1933).

By August 13th, Tay was back at Pathe and meeting with the AMPP’s Colonel Jason Joy. The picture was screened for Joy on August 18th, and the colonel was pleased with the results. Outside of possible local censorship problems for a shot or two, he felt Pathe would have no problem exhibiting the show, or getting a production seal for the picture from the AMPP.

The film got its seal but did undergo some censor eliminations. The New York Board of Censors cut some shots of girls standing in the doorway of Havana’s red-light district; a shot of Frankie putting money she’s stolen into her bosom; and a shot of Frankie actually handing money over to Johnnie. The Massachusetts censors deleted a shot of Frankie picking pockets and the shot of the knife protruding through the door prior to Johnnie’s reeling back against it. Pennsylvania cut the pickpocket shots, Johnnie throwing the knife, the scene of Johnnie demanding money from Johnnie, and a shot of the drunken Annie crossing the street while men stand and jeer at her.

The film got its seal but did undergo some censor eliminations. The New York Board of Censors cut some shots of girls standing in the doorway of Havana’s red-light district; a shot of Frankie putting money she’s stolen into her bosom; and a shot of Frankie actually handing money over to Johnnie. The Massachusetts censors deleted a shot of Frankie picking pockets and the shot of the knife protruding through the door prior to Johnnie’s reeling back against it. Pennsylvania cut the pickpocket shots, Johnnie throwing the knife, the scene of Johnnie demanding money from Johnnie, and a shot of the drunken Annie crossing the street while men stand and jeer at her.

The British censors were handier with their scissors, cutting the shot of Johnnie throwing the knife to murder Red; the scene of Frankie returning to her room with Johnnie they felt established her as an immoral woman; and trimming the fight scene, which they felt was excessively brutal. The picture was condemned in Quebec since their censors would have been forced to cut out too much, thus affecting the continuity of the story, while Alberta initially rejected the film but finally approved it after some of the New York-Pennsylvania-Massachusetts cuts were made.

On August 19th, Her Man was previewed at the Golden State Theatre in Riverside, California. The performances of Holmes, Rambeau, and Cortez were praised, and the preview cards were generally favorable. “Best picture I’ve seen in weeks,” said one. Other cards complained of “Too much drinking and no story,” and another remarked “Fight in saloon is too long drawn out and too much rough and tumble. Few could survive a fight like that, least of all, the principals.” One viewer was downright outraged: “Is it a possible fact that our actors have stooped to such a level of degradation. Apply the torch to that film and raise your standard.”

A second preview was held on August 27th at the Fox Redondo Theatre in Redondo Beach, and a third at Los Angeles’ Ritz Theatre on September 5th. The cards were uniformly favorable, with thematic comparisons made to Borzage’s Seventh Heaven (1927), and the character of Frankie compared to Walsh’s 1928 Sadie Thompson (7).

Her Man is years ahead of its time in technique, with incessant camera movement and Garnett’s fondness for overhead tracking shots in early evidence, such as the shot of Vince Barnett moving through the Thalia crowd balancing a tray of drinks. As an “underworld” picture, it offered audiences a different slant – knives and fists instead of machine guns. Garnett creates a wholly insular world, and the picture seems European in flavor, more like an early Rene Clair film rather than a mainstream Hollywood studio movie. Pathe engineers developed a portable sound mixer for travelling shots, used for the first time on Her Man, and Garnett took full advantage of this new technological toy (8).

The film opened to excellent notices in the trades: “To my mind,” wrote Douglas Hodges in Exhibitors Herald-World, “Garnett’s fight sequence outdoes any heretofore” (9). Motion Picture News remarked,

Besides being very well acted this story of Frankie and Johnnie has received exceptionally fine direction by Tay Garnett … The care with which the delicate nature of the story is handled is apparent. Evading of censorable scenes is done in a most skillful manner. (10)

“This is the best drama of its kind to come along in quite a while,” Film Daily remarked:

Story has deep appeal, principally because of the loveliness of the heroine, Helen Twelvetrees, and the boyish charm of the hero, Phillips Holmes. And the action has real guts. A fight scene in the dive … is a robust performance that should just about lift the folks off their seats. The entire cast is aces, and the same goes for the direction and the acting all-around. (11)

The New York reviews were also overwhelmingly positive:

New York Evening Journal: “A vigorously contrived film with plenty of action … Director Tay Garnett has infused the piece with a lusty swing.” (12)

New York Tribune: “A real motion picture, stemming from the days when a photoplay possessed the proper regard for dramatic vigor, robust comedy, frank romanticism and shrewd pictorial skill.” (13)

New York Sunday News:

Tense action and excellent acting, accompanied by swell direction, make Her Man a crackerjack talkie; a feather in the cap of Tay Garnett … [Garnett] has done an extra-special job on an extra-special action film. You’ll be interested through every minute of Her Man. It’s a corker. (14)

New York American: “For straight, out-and-out popular entertainment, it hasn’t been topped on Broadway in a month of Sundays. Brisk in pace, it is a happy blend of thrills and laughter which is bound to please the picture publics.” (15)

New York Evening Post:

[The climactic fight] is the grandest, maddest, wildest battle I have ever seen either on or off the screen … It is a tremendous scene, and it is directed with consummate skill. In this matter of direction Her Man can teach a lesson to the majority of directors. It moves fluently from incident to incident, letting the camera tell the story and wasting no time on dialogue. It is action throughout, without those lapses into static conversation that have been the bane of so many talkies. Director Tay Garnett has done an admirable job with Her Man. (16)

Pathe’s advertising exploited the sordid side of the picture: “The Whirl of Life in the streets of scarlet had caught this girl in its maelstrom of unbridled passion – until Her Man rescued her from a life that is a mockery and a living shame.”

Shortly after release, yet another controversy arose when the Cuban Embassy protested about the Havana setting. Pathe half-heartedly denied that the film was set there, saying that since Prohibition was in effect in the United States, it had to be set on “a mythical island.” A Pathe publicity man had seen the film and contrary to the studio’s instructions, referred to the background of Her Man as Havana. Since there were already 150 prints in circulation, it would require sending a cutter to every exchange center in the country to remove the identifying shots, but they agreed to eliminate two views of the Morro Castle from whatever prints that had not yet been shipped, promised not to mention Cuba or Havana in their advertising, and made an official apology to the Cuban Embassy.

Pathe had problems with Her Man in Middle America as well, in an editorial in a Grand Rapids, Michigan newspaper entitled “Where is Mr. Hays?”:

Cuba has protested to the State Department against display of the sound film Her Man on the grounds that it presents a misleading picture of life in Havana. Those who saw the production in Grand Rapids last week will agree that complaint is in order from the Cubans or anybody else; but not because Havana is maligned. The `distorted version of life’ against which Dr. Baron, the Cuban charge d’affairs, inveighs, happens to be set in Havana; but that is a mere incident. The real objection to the production is that it is rotten to the core, rotten in theme, in background, and in action. It might have been accepted 20 years ago as entertainment for a beer garden stag party, although even then there would have been blushes among the spectators. It has no proper place on the screen, to be seen and heard by the average movie audience of adults and children. Such pictures as this cause us to wonder just what it is that Will Hays does to justify his retention as director general of the movies, and when he does it. (17)

Blue-nosed protests continued as the film’s release spread to neighborhood houses throughout the country. The chairperson of the Motion Picture Advisors in the Massachusetts State Federation of Women’s Clubs wrote to the AMPP complaining that Her Man had been screened to a Saturday afternoon matinee audience of 500 children on a double bill with Santa Fe Trail; she denounced the film as “a degrading picture from every standpoint and the most drinking picture we have ever seen” (18).

All the moral crusading only helped Her Man‘s box office, and it became one of the highest grossers in the company’s history. Garnett’s first unqualified success, it had made back eight times its negative cost only two years after release, and was still running at the same Paris theatre, the Moulin Rouge at Boulevard de Clichy in Montmartre (still extant), in 1933. Garnett became the studio’s new fair-haired boy, and had his salary raised to $2,550 per week. Gloria Swanson saw the picture at preview, loved it, and courted Tay to direct her.

In October Pathe announced that Garnett and Swanson, an industry superstar, would make Rockabye together, a mother love melodrama about a promiscuous actress who adopts a baby, scripted first by actress Laura Hope Crews, then by Elliot Clawson from an unproduced Lucien Bronder play; a month later it had been cancelled. Swanson tried to get it made first at UA, and then with Samuel Goldwyn before it was eventually realized without her the following year at RKO-Pathe, starring Constance Bennett and Joel McCrea (replacing Phillips Holmes), started by George Fitzmaurice and completed by George Cukor.

Columbia purchased remake rights for Her Man, and re-did the film in 1939 as Café Hostess. Consequently the original film languished in the vaults, unseen for years, making it a virtually unknown title in this country. Like so many American movies, Her Man was preserved by the Cinematheque Francaise, and had its first American screening in decades on December 22, 1967 in a special Museum of Modern Art series. The American Film Institute restored a print in the early ’70s, but it was infrequently revived; there were showings in New York at Joseph Papp’s Public Theatre and the repertory house Theatre 80 in the 1980s. “Memorable,” said Andrew Sarris in his pioneering work The American Cinema, “in the 1930 Her Man are the extraordinarily fluid camera movements that dispel the myth of static talkies, a myth treated as gospel in the official film histories of the period” (19).

The movie showed up in a Columbia Pictures retrospective in Los Angeles in 1981, and Kevin Thomas wrote, “There’s a breeziness and sincerity in Her Man that was to characterize Garnett’s later work – this was only his sixth film – and also some of the guilt and fatalism of his most famous film, The Postman Always Rings Twice” (20).

William K. Everson screened it on a Tay Garnett double bill with She Couldn’t Take It (1935) in his New School series in New York City in 1990:

Garnett wisely concentrates on melodrama and aborts some of the potential sub-plots; the suggestion that Marjorie Rambeau might in fact be Twelvetrees’ mother is left at that, a mild suggestion. All in all, Her Man holds up well as rowdy, exciting and sometimes quite moving melodramatic entertainment. (21)

Martin Scorsese called much-needed attention to the picture in his compelling 1995 documentary and book A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese through American Movies:

Traditionally, film historians insisted that at times movies stopped moving. But the myth of the static camera has been dispelled now that so many films of that period are being rediscovered. There were some who refused to be shackled or paralyzed – directors such as Rouben Mamoulian, Frank Capra, William Wellman, Tay Garnett, all of whom can be credited with getting the camera moving again. Most Tay Garnett pictures of the early thirties feature fluid camera moves and even very long takes. In Her Man, for instance, you have to admire how skillfully the camera follows a tray with two glasses across the dance floor of a honkytonk bar. The choreography looks effortless, but trust me, long shots like these must have been very hard to achieve. (22)

Her Man received a new lease on life in 2015 when the original camera negative was discovered in the Columbia Collection at the Library of Congress. It was restored in 4K by Sony and The Film Foundation, and re-premiered at the Museum of Modern Art for a week in late March/early April 2016 in a program titled “Her Man: A Forgotten Masterwork in Context.” The mini-retrospective curated by Dave Kehr also screened Celebrity, The Spieler, Garnett’s 1953 Main Street to Broadway, and Chester Erskine’s independent version Frankie and Johnny (1936, Republic) starring Helen Morgan and Chester Morris.

Her Man will screen at the Reel East Film Festival at 5pm on Saturday, June 17, hosted by Tay’s daughter, Tiela Garnett.

Endnotes:

This essay is an excerpt from the forthcoming biography Hollywood’s Forgotten Master: The Life and Times of Tay Garnett.

The production history of Her Man comes from the Pathe Collection at USC Special Collections.

- Tay Garnett, letter to John V. Wilson, May 9, 1930, in the AMPP Collection, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

- Maidee Crawford, “Under the Spotlight,” Hollywood Filmograph, June 14, 1930.

- Projecting intelligence and sensitivity, Holmes’ work in Her Man initiated a series of starring roles in the early 30s working for such distinguished directors as Howard Hawks (The Criminal Code), Josef Von Sternberg (An American Tragedy), Ernst Lubitsch (Broken Lullaby), Woody Van Dyke (Night Court, Penthouse), George Cukor (Dinner at Eight), and Dorothy Arzner (Nana). Holmes joined the Royal Canadian Air Force when World War Two broke out in 1941. After completed his training in Winnipeg, he was killed in a mid-air collision with six of his classmates on August 12, 1942, on the way to their assignment in Ottawa.

- Helen Twelvetrees shot up the ranks of Hollywood starlets when she was named a Baby Star by the Western Association of Motion Picture Advertisers (WAMPAS), the highest accolade for a young aspiring actress; other baby WAMPAS ingenues that year were Jean Arthur, Anita Page, and Loretta Young and her sister Sally Blane. After a couple films for Fox, she ended up with a contract at Pathe. Her Man made her popular with public (she married one of the stuntmen, Jack Woody, six months after the movie opened), and she starred in a rapid succession of films, unmemorable save Howard Higgin’s The Painted Desert (1931), Garnett’s Bad Company, William Seiter’s Is My Face Red?, and George Archainbaud’s State’s Attorney. By the end of the ‘30s her career was over; she died in 1958 from an overdose of sedatives.

- This set had served as the Poto-Poto saloon in Von Stroheim’s Queen Kelly (1929).

- American Film Institute Oral History with Tay Garnett, interviewed by Charles Higham, Los Angeles, 1973.

- Preview Cards, “Her Man,” Pathe Collection, USC Special Collections.

- Variety June 25, 1930.

- Douglas Hodges, “Her Man,” Exhibitors Herald-World, September 13, 1930.

- Bill Crouch, “Her Man,” Motion Picture News, September 13, 1930.

- “Her Man,” Film Daily, September 21, 1930.

- Rose Pelswick, “Action Aplenty in Her Man” New York Evening Journal, October 4, 1930.

- Richard Watts, Jr., “Her Man is Grand Entertainment,” New York Tribune, October 4, 1930.

- Irene Thirer, “An Extra Special Action Film,” New York Sunday News, October 5, 1930.

- Regina Crewe, “Entire Cast Merits Three Hearty Cheers,” New York American, October 4, 1930.

- Thornton Delehanty, “Racy and Exciting,” New York Evening Post. October 4, 1930.

- “Where is Mr. Hays?” in Grand Rapids Herald, October 20, 1930.

- Mrs. Oscar Blaidell, Wollaston, Mass., letter to AMPP, New York, February 15, 1931.

- Andrew Sarris, The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1968, p. 130.

- Kevin Thomas, “Spruced-Up Theater Offers Her Man,” Los Angeles Times, October 28, 1981.

- William K. Everson, “Notes: Two Free-Wheeling TAY GARNETT Melodramas,” New School of Social Research, February 9, 1990.

- Martin Scorsese and Michael Henry Wilson, A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese through American Movies, New York: Miramax Books/Hyperion in association with British Film Institute, p. 82.

John Andrew Gallagher is the director of indie cult comedy The Deli (1997), in addition to the films Blue Moon (2000), Men Lie (1994), Cupidity (2004), Street Hunter (1990) and Beach House (1982). His latest features are The Networker, set for September 2017 release from Sony’s The Orchard, and as a writer/producer, the switch comedy Sam, executive produced by Mel Brooks. He is also a film historian and the author of Film Directors on Directing, Nothing Sacred: The Cinema of William Wellman (with Frank Thompson), Hollywood’s Forgotten Master: The Life and Times of Tay Garnett, and entries in Peter Bogdanovich: Interviews and Between Action and Cut.

One thought on “When Tay Garnett Met Frankie and Johnnie: Her Man (1930)”