A Book Review Essay by Andrew Kolarik.

[Author Pardis Dabashi] makes the case that an understanding of modernist authors’ relationship to cinema might allow their works to be read in a different light….”

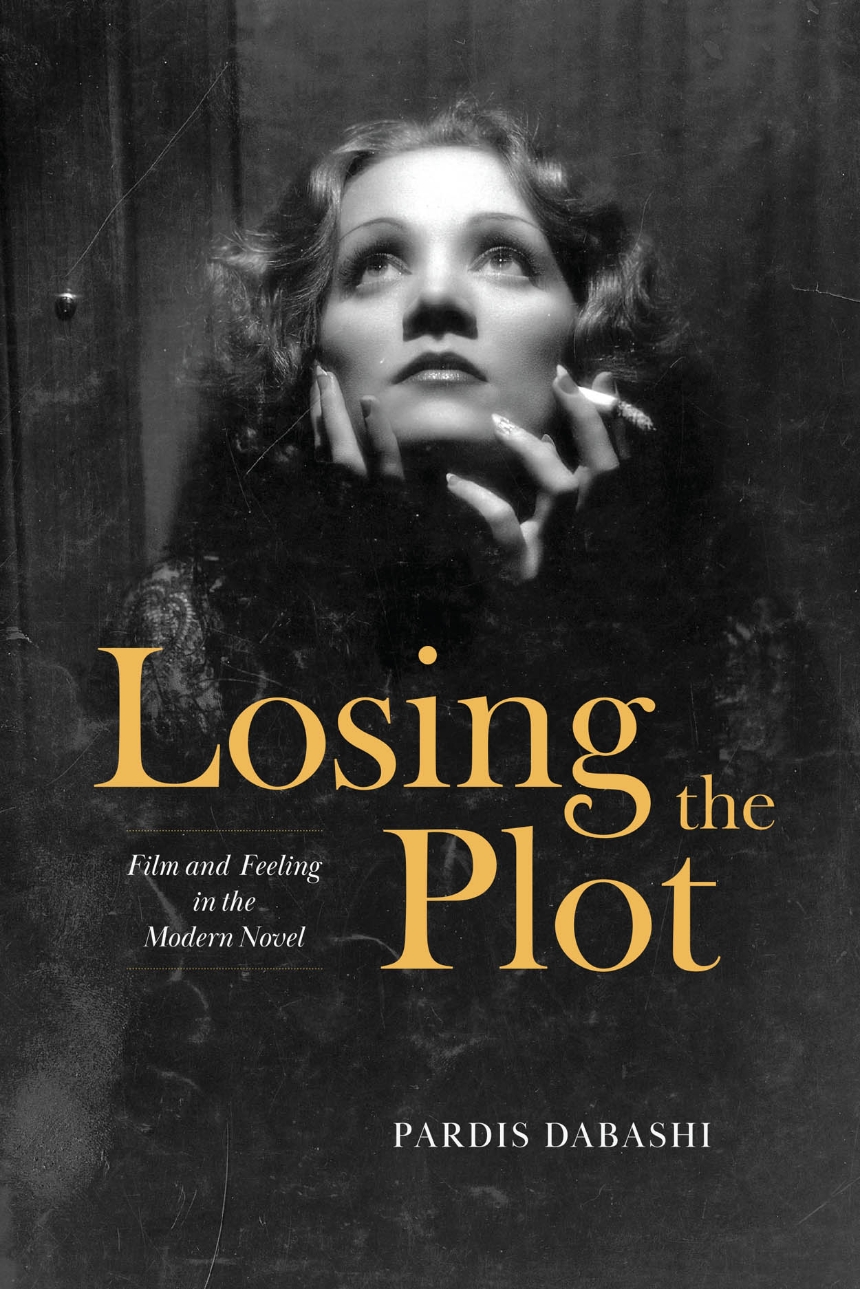

Losing the Plot: Film and Feeling in the Modern Novel (The University of Chicago Press) by Pardis Dabashi explores modernist literature’s penchant for squashing plot as a narrative device, the ambivalence of the authors in executing this in their writing, and the role of cinema in all this, and it faces a tricky challenge. Modernism’s relationship to plot turns out to be a rather ambiguous and complex construct, and the book has to navigate this as it makes the case that an understanding of modernist authors’ relationship to cinema might allow their works to be read in a different light, which exposes a longing for the comfort that the plot provides the characters, even as they boot plot itself out of their novels. What animates the text is a critical approach far more aligned with treating history as a deeply tactile, affective thing, rather than dealing in straight chronology where history is just one event after another which we know happened with total certainty. Dabashi gives the example of the author Nella Larsen, who at a point in her life when she was struggling with loneliness, a cheating bastard of a husband and a proclivity for substance abuse and depression, went over and over again to watch Greta Garbo playing Marguerite Gautier in Camille (1936). This was a film where the flawless Garbo (radiant even as she dies in her lover’s arms) is saved from the same sort of social excommunication and mental suffering that tormented the character Helga Crane in Larsen’s novel Quicksand (1928). Being equipped with this knowledge and the background to it makes the reading of Quicksand resonate very differently. It enriches the text when the reader is immersed in the swirl of cultural events and upheavals surrounding it, and suggests that rather than abandoning plot, the novel perhaps instead laments the lack of formal resolution that plot would provide to the challenges faced by its main character. This revitalizing critical approach, which must have required careful research and objectivity from the author (the risk of conjecture and the temptation to fill in the blanks is high), offers the chance to deepen the experience and understanding of what is going on with the text of the modernist novels that are considered by Dabashi, and their relationship to plot and the reassuring security it provides. Such an approach can also help give focus to such a critical appraisal, which might otherwise be lost due to shortcomings along racial fault lines, endemic to traditional approaches.

The title Losing the Plot refers to how modernism as a literary form arguably does away with plot as an organizing force where events have consequences that drive the narrative onwards, which was typical for nineteenth-century fiction. One way that the modernists moved away from plot was to get rid of consequences, so that a lot happens but nothing changes. This occurs in Flaubert’s Sentimental Education (1869), where despite the upheavals caused by the French Revolution, tyranny and oppression continues in the guise of different faces and authorities, and modern life consists of a series of events that change nothing. Losing the Plot starts out with a stunning display of even-handedness, discussing the idea of how the rejection of plot was something of a defining characteristic of modernist authors, and then seems to torpedo this premise by offering up the caveat that maybe modernist authors were not all that keen on canning plot in any case, and that no one really thinks they fully rejected plot anyway. The text carefully considers how perhaps modernism does not so much lose the plot, as reconfigure the usual terms of plot to suit specific social and historical goings on (which would make for a far less catchy title for the book). What becomes apparent, is that the relationship between modernism and plot is a complicated one, and that the book is going after the idea that modernist writers witnessed how cinema was doing an excellent job of delivering what the traditional bourgeois novel did in terms of tales of normality and security, and started to miss (and long for) these elements. As the book points out, film offers an unparalleled means of immersing oneself in the narrative on show, and of identifying with the audience. A traditional plot where everything is resolved and wrapped up in a happy ending had better happen if Hollywood expected to continue to rake in the cash it was making. The costs associated with jettisoning (or not?) the plot onscreen or in books, such as the alienating incomprehensibility of early-cinematic spectacles or elements of modernist text, are discussed in detail by Dabashi, who explores the intriguing idea that those modernist authors really rather wanted to embrace the limits and comforts provided by an easy to follow narrative. With the viewpoint that they enjoyed films as consumers rather than watching with a critical eye, the book looks into how these experiences may have touched the authors in meaningful ways, which then took a hand in shaping the authors’ characters, in their choices and their yearnings.

The starting point for Dabashi’s arguments is Tzvetan Todorov’s theory of plot, where the narrative begins with a stable situation in which the state of equilibrium is disrupted by some power or force, and there are significant consequences (Oedipus discovers that his wife is his mother, which transforms good fortune to bad and wrecks his life). The modernist novel subverts this in various ways, perhaps by having unrelated events occur one after the other, and stuff just happens rather than forming a coherent whole. Grammar confuses the reader and messes up their comprehension of what is going on. Such mind-sets provide the bases for novels such as Franz Kafka’s The Trial, in which Dabashi highlights that experience produces only nightmarish disorientation rather than knowledge. What modernism does do is set things up to illustrate just how spectacularly urban decay and living in a monolithic, unchanging socio-political wasteland can erase any sense of transcendent meaning from life (fun stuff). Modernism as a technique is also suited to using style to highlight queer desire, which is discussed throughout the text and in an examination of the relationship between Djuna Barnes, author of Nightwood (1936), and the actress Marlene Dietrich. Nightwood, a respected example of queer modernism, is an autobiographical novel. It is described by Dabashi as “one of the most stylistically difficult and narratively contorted novels of the modernist period, [which] does not so much tell a story as it allows narrative energy to accrue” around the character of Robin Vote, who stood in for an acquaintance of Barnes called Thelma Wood (another cheating swine), with who Barnes had an affair for eight years before Barnes left her. So why tortuously contort the narrative? Because queer desire in the nineteenth-century novel had to assert itself through style, and form, and plot here is argued to be a construct unsympathetic to queer marginality. Dabashi explores the romantic elements of modernist desire (and the Nightwood characters’ longing) for the relief and meaning provided within the realm of plot, and the protection afforded by a conventional story. Barnes admired Marlene Dietrich’s films and her distant, uninvested portrayal of characters not bothered about the need to fulfil the typical movie requirements of ending up with the male lead, not dissimilar to the Robin Votecharacter in Nightwood. Barnes herself was not built this way, and was invested deeply in her relationship with Wood, and wanted the succour of a monogamous relationship with her and a happy ending. In the context of this, the case is made that the reading of Nightwood changes from a refusal to work within the confines of plot and rejecting it in line with the expression of queer desire, to a reading that acknowledges that all the disinterest and lack of pandering to social constraints in the world won’t change the need and the yearning, to find solace within the confines afforded by those very constraints.

The speculative approach the book takes is intriguing, and appears to have been undertaken with the appropriate safeguards against hazarding a guess as to what modernist authors such as Larsen and Faulkner were feeling while watching their favourite films.”

The book develops its arguments by exploring the implications that in an interview about his modernist masterwork The Sound and the Fury (1929), William Faulkner compared his novel to the advent of cinema, where the poor lighting, warped lenses and wretched gears took eighteen years to smooth and clarify the picture. The Sound and the Fury describes the ruin of the Compson family in Jefferson, Mississippi, as they variously lose their wealth, their reputation, or drop dead. The text delves into Faulkner’s interview comment in depth, describing how the first eighteen years of cinema started out by relying on dazzling images and the novelty of the medium rather than story, before giving way to “narrative integration” as the years passed. In a similar vein to that of early cinema, Faulkner’s fragmented, glimpsed, and sometimes incomprehensible prose, recounted by the character Benjy Compson in the first section of the book, is stripped of context by making everything entirely of the moment (“We watched the tree shaking. The shaking went down the tree, then it came out and we watched it go away across the grass. Then we couldn’t see it”). This achieves Faulkner’s aim of making the story effective by telling it through a character able to know what the events were that happened, but not why they happened, and effectively shoots down the implications of the events in the process of telling the story (or as a cinematic equivalent, showing the scenes). The dominant effect of all this a heavy emphasis on wonder, surprise, curiosity and astonishment, perhaps paralleling the experience of those early cinema-goers. The second section of the book is told by Benjy’s brother Quentin Compson, where Quentin’s focus on imposing meaning on the world begins to imbue the prose with narrative change, and Dabashi discusses the difference between Quentin’s perception and that of his brother. Dabashi speculates about a link between the text and the beginnings of narrative cinema that was unlocked by the screening of the Edison film company’s Electrocuting an Elephant (1903) that Faulkner may very well have seen, where incidents such as sending fatal electric current through poor Topsy the Elephant, or Quentin taking his own life, constitute irreversible change rather than isolated, fragmented events. The Sound and the Fury progresses to a section that is narratively driven, fully comprehensible and full of nastiness as told from the viewpoint of Jason Compson, embittered and racist and thoroughly unpleasant. Losing the Plot suggests that in giving way from the modernist rejection of plot to full-on narrative, what was lost was the “ethically emancipatory potential” as the shackles of narrative storytelling imposed themselves on Faulkner’s novel and on cinema.

There are points in the book where a little more explanation to the uninitiated would be nice. “Who the fuck is Darl?” is a fair question when this name first pops up out of the blue, before it becomes apparent that this is a character in Faulkner’s As I lay Dying (1930). There are places where the text is impenetrable seemingly for the joy of it, which can make the main messages conveyed by the writing rather murky, but these are balanced by some nice flourishes, such as “…he is nonetheless muscling the present tense into slowing down so that it can accommodate his imagery.” There are also some sections where cinematic considerations seem to temporarily fall by the wayside, such as the entertaining fixation on style and modernist technique in the part extensively discussing As I lay Dying, where cinema is mentioned not at all. Also, the assumption that modernist authors enjoyed films as consumers rather than critics is an interesting one, as is the supposition that going to the movies was a means to distract the authors and soothe themselves while avoiding the challenges faced by personal circumstances and the modern world. Would not such authors, even the ones who were medicated and out of their tree, who were likely tuned into the creaking machinations of plot in those early days of cinema even more than modern audiences and critics, perhaps not be predisposed to spot such occurrences and revile them the way they (may have) done so when making it their mission to critique nineteenth-century realism? It is kind of nice that Dabashi implicitly seems to take the position that hate-watching was not a consideration for these great authors, but it is possible to wonder about this. Overall though, the speculative approach the book takes is intriguing, and appears to have been undertaken with the appropriate safeguards against hazarding a guess as to what modernist authors such as Larsen and Faulkner were feeling while watching their favourite films. Dabashi is open about preferring to run the risk of being wrong rather than playing it safe, if the result opens up new lines of inquiry. By presenting alternative readings sparked by the implications of the modernist writers’ relationship with cinema, Losing the Plot appears to conclude that the power wielded by the tyrannical need for plot in our own lives should not be underestimated. The desire for the comforts of aesthetic appeal and belief that everything will work out fine, if things could just happen in the way we would like them to, leads to the continuation and proliferation of the political and social structures around us. Effectual political change requires acknowledgment of this, and cinema might just offer the key to this realization. That is quite a finish, and might just get you by surprise.

Andrew Kolarik is a Lecturer at University of East Anglia and has previously worked at Cambridge University, University of London, and Anglia Ruskin University. His criticism, poetry, and fiction have appeared in Pulp Metal Magazine, Supernatural Tales, Carillon, Eunoia Review, Horla, Yellow Mama, and Between These Shores Literary and Arts Annual.