A Book Review by Wheeler Winston Dixon.

Let’s just start by saying that this is an excellent book. I get stacks of new titles every day from publishers, and it takes a lot for a book to really jump out of the pile and interest me, particularly on a topic that has been researched as thoroughly as the Hollywood Blacklist. But Rebecca Prime’s Hollywood Exiles in Europe: The Blacklist and Cold War Film Culture (2013) is exceptional, and part of an equally exceptional series of books from Rutgers University Press, “New Directions in International Studies,” ably edited by Patrice Petro.

The Hollywood Blacklist is always an important topic, but there’s been so much written about it that one would think that all possible avenues of inquiry have been pursued. But that’s not the case: Prime’s book is fresh, original, written in a direct and accessible manner, and adds a great deal of new material to the existing literature on the era. This is a book, in short, that demands one’s attention.

What distinguishes Prime’s book above all else is the sense of urgency she brings to her examination of the key figures affected by the blacklist; Joseph Losey, Ben Barzman, Jules Dassin, and other well known Hollywood figures who decided it was better to leave America, then in the grip of madness, rather than battle it out with the openly hostile “authority” of the House Un-American Activities Committee.

This is a familiar tale, but what Prime makes clear in her study is just how difficult it was for these talent writers, directors and producers to survive in England, which wasn’t as welcoming as is generally assumed in hindsight. The FBI and the HUAC still shadowed these exiles, with the help of the British authorities, and so they were never really free of surveillance.

Though some, like Losey, managed to completely reinvent themselves, and create work of lasting worth and brilliance, numerous others were plowed under by the effects of the Blacklist, and never really regained their footing either in Hollywood or abroad. By concentrating entirely on those who left the United States, rather than dealing with the entire social landscape of the Blacklist, Prime can bring into sharp focus both the promise and difficulty of working in an adopted country.

As one example, Prime considers the stunted career of Bernard Vorhaus, whose Hollywood career was cut short by the Blacklist, and who never really recovered. Jules Dassin managed to get his film Rififi off the ground in Europe, but after that, he fell afoul of the Cahiers critics, who felt that he was deserting the supposed grittiness of his American film The Naked City, and though he finally found some sort of home in Greece, and had a huge hit with Never On A Sunday, he never really felt, as Prime makes clear, that he had a national identity of his own.

And while England offered some sort of sanctuary to these cultural refugees, all too often they were still forced to work under pseudonyms, for cut-price producers like Edward and Harry Danziger, churning out episodic television programming simply to stay alive, whether as screenwriters or directors. Since they couldn’t even use their own names, all their previous work counted for nothing as a bargaining chip, and they worked for pathetically small salaries as virtual unknowns, really starting all over again at the bottom of the ladder.

As Joseph Losey said of his work for the Danzigers, who prided themselves quite publicly on making the cheapest feature films and television series in the business, “most of the time you couldn’t rehearse, and you had to film the whole episode in a half day. I have no fond memories of the experience, which was simply a means to an end. Financially, I needed the work; that’s really all I can say about it” (56).

In addition, most of the filmmakers had to renew their residence permits every thirty days, and sometimes had their passports pulled for the most capricious reasons by the British authorities. The decision to leave Hollywood and America was never an easy one, and those who stayed as “friendly witnesses,” such as Elia Kazan and Edward Dmytryk had a much easier time of it, as the HUAC intended.

Prime also offers a compelling account of the career of the oft-neglected Hannah Weinstein, a progressive activist whose small studio proved a genuine haven for Blacklisted writers and directors, and had a genuine international hit with the long running television series The Adventures of Robin Hood, which was almost entirely staffed by fugitives from the Hollywood dream factories, working under assumed names.

There’s also a sense of “lost community” brought out here, which I’ve never seen sketched as well anywhere else, how Weinstein’s Chelsea house, for one example, served as a sort of salon for these filmmakers on the run. Prime also details the sad story of how financial mismanagement brought an end to Weinstein’s small studio, but also the unexpected happy ending, in which Weinstein returned to a post-HUAC Hollywood in the 1960s and 70s, and wound up as the producer of such hit films as Greased Lightning and Stir Crazy (173-174).

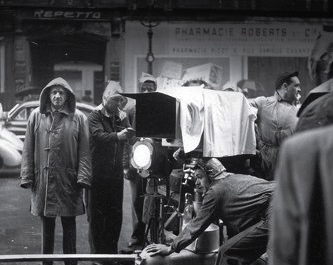

There’s so much more here; interviews, rare photographs, and massive amounts of original, detailed research from primary sources, which gives us, for the first time, a really authoritative account of what it was like to be on the run from one’s home and livelihood in a world gone mad. One also gets a sense that out of these difficult circumstances, for some, a complete renewal was possible, with the result that their work actually improved as a result of the difficulties they faced on a daily basis. But for others, there was only oblivion.

There’s so much more here; interviews, rare photographs, and massive amounts of original, detailed research from primary sources, which gives us, for the first time, a really authoritative account of what it was like to be on the run from one’s home and livelihood in a world gone mad. One also gets a sense that out of these difficult circumstances, for some, a complete renewal was possible, with the result that their work actually improved as a result of the difficulties they faced on a daily basis. But for others, there was only oblivion.

In sum, I can’t say enough good things about this book; it’s an enthralling read, beautifully written, immaculately detailed, and an absolute page turner, with each new chapter offering fresh insights on the lives and works of these talented artists forced to leave their homeland. The care and attention to detail here are everywhere evident; go to Amazon and buy a copy, and read it, for a fresh and utterly original view of Hollywood exiles in the 1950s.

Wheeler Winston Dixon is the James Ryan Professor of Film Studies, Coordinator of the Film Studies Program, Professor of English at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, and, with Gwendolyn Audrey Foster, editor of the book series New Perspectives on World Cinema for Anthem Press, London. His newest books are Cinema at the Margins (2013), Streaming: Movies, Media and Instant Access (2013); Death of the Moguls: The End of Classical Hollywood (2012); 21st Century Hollywood: Movies in the Era of Transformation (2011, co-authored with Gwendolyn Audrey Foster); A History of Horror (2010), and Film Noir and the Cinema of Paranoia (2009). Dixon’s book A Short History of Film (2008, co-authored with Gwendolyn Audrey Foster) was reprinted six times through 2012. A second, revised edition was published in 2013; the book is a required text in universities throughout the world.

My undergrads are fascinated with the blacklist and HUAC, as one would expect. Since my classes are comprised mainly of non-majors (while many are in literature, art history or related fields), I’ve struggled to find an approachable text for them. So I appreciate your review, Wheeler, since this text may suit their needs.