By Jonathan Monovich.

For its Australian setting and premise of a man’s descent into insanity, The Surfer unsurprisingly has similarities to the late Ted Kotcheff’s Wake in Fright (1971), but the charm of The Surfer comes from its overt love for Frank Perry’s The Swimmer (1968)….”

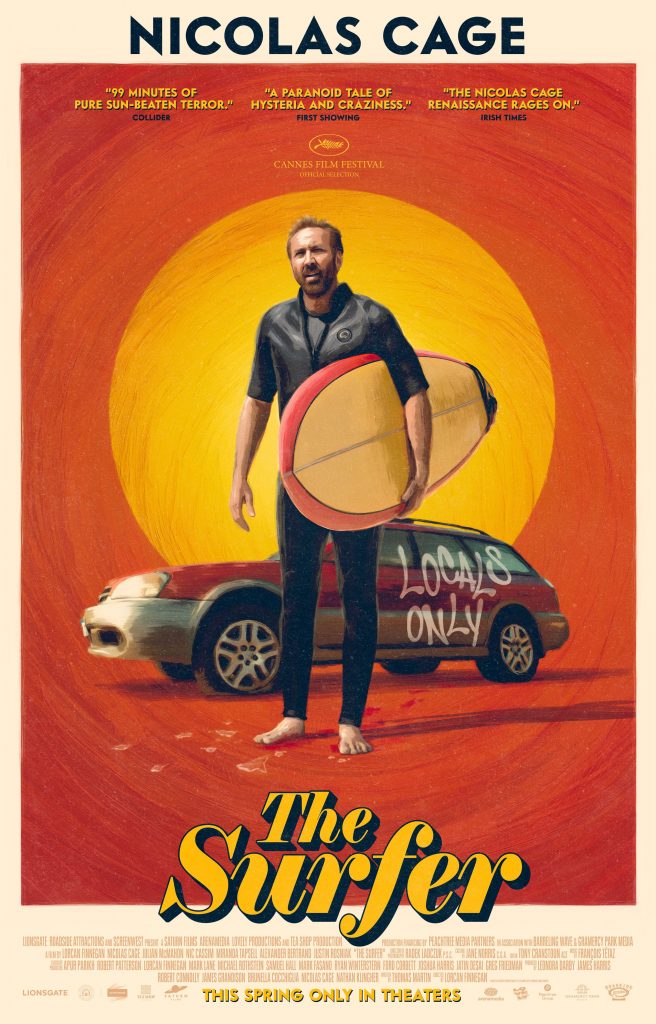

Though marketed as a deranged Nicolas Cage revengeamatic, The Surfer (2024) is more narratively complex. Elements of Cage’s performance in The Surfer are familiar to other entries of the infamous actor’s chaotic filmography but not as unhinged as The Wicker Man (2006) or Mandy (2018). Of course, Cage’s signature expressionism remains entertaining to watch, but what makes The Surfer most noteworthy is the film’s use of homage and heavy inclusion of cinematic references. The Surfer comes from a place of respect for the offbeat cinema of the turn of the sixties into the seventies. For its Australian setting and premise of a man’s descent into insanity, The Surfer unsurprisingly has similarities to the late Ted Kotcheff’s Wake in Fright (1971), but the charm of The Surfer comes from its overt love for Frank Perry’s The Swimmer (1968). From the yellow title cards to the dramatic finale, The Swimmer clearly guides the The Surfer’s structure. Without having seen The Swimmer, The Surfer’s setup may come off as a tease. Those privy to The Swimmer will likely be more forgiving of The Surfer’s inconsistencies and instead focus on the film’s effort. Imitation is the greatest form of flattery, and the sheer existence of The Surfer should be seen as an accomplishment in itself. Anyone able to string together a theatrically released film that exudes passion for a cult classic like The Swimmer in today’s industry deserves recognition.

Like other “bad day” genre films, The Surfer follows a spiraling story arc and an unraveling narrative that eventually arrives at a clever denouement. Just as Irish director Lorcan Finnegan confronted situations that eerily felt too good to be true in Without Name (2016), Vivarium (2019) and Nocebo (2022), The Surfer similarly starts with a feeling that something is off. In place of supernatural forestry, inescapable suburban neighborhoods, or delusions brought on by the arrival of a caregiver, The Surfer focuses on a father (Cage), his son (Finn Little), and their inability to enjoy a surf at the beach. As soon as the father/son duo set foot to sand, the locals proclaim “don’t live here, don’t surf here.” This saying, said many times throughout the film, serves as a mantra for the surfers and their hostile localism. Ironically, Cage’s character supposedly did live there as a child, and the reason for his return happens to be an effort to reclaim his childhood home. Crowned as the “Bay Boys,” the abrasive surfers possess a strange sense of pride in declaring the water their turf. They are not of the stereotypical surfer breed, defined by a laidback, easygoing, demeanor. Whereas Jeff Spicoli (Sean Penn) of Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982)professed “all I need are some tasty waves, a cool buzz, and I’m fine,” the Bay Boys are more in line with Bodhi (Patrick Swayze) and the troublemaking “Ex-Presidents” of Point Break (1991). The concept of a foreigner’s unwelcomed stay in a small Australian town at Christmastime clearly comes from Wake in Fright. Like the barflies of the Yabba, the Bay Boys wreak havoc on the beach with their rabblerousing, but, whereas much of John Grant’s (Gary Bond) problems were self-inflicted through irrational decision-making under the influence, Cage’s character, billed “the Surfer,” becomes plagued by psychological distress that stems from an unwillingness to let go of the past. Like Ned Merrill (Burt Lancaster) in The Swimmer, Cage’s performance as the Surfer can be found largely in the eyes. For this reason, The Surfer’s cinematographer, Radek Ladczuk [The Babadook (2014), The Nightingale (2018), The Peasants (2023)] cleverly employs frequent close-ups on Cage’s sun strained eyes in the fashion of David L. Quaid’s impressive camerawork.

Whereas The Swimmer was more concerned with social pressures brought on by the neighborly competition of suburban life and the fleeting American dream, The Surfer fixates on longing for the past, nostalgia for a time free of personal conflict, and satirizing hypermasculinity. The Bay Boys leader, Scally (Julian McMahon), whose overly white teeth noticeably contrast his tan skin, sports a red hooded towel. The look can be described as a Sith lord of the sun. Unwilling to compromise, Scally makes enemies with the Surfer as he won’t leave the beachfront. All the while, an increasingly frustrated Cage haggles with his real estate agent for his childhood home, but the prospect of reliving the past becomes further and further out of reach. The Surfer’s desire for his former life comes from his current disappointments; he lives as a divorcee, his son acts standoffish, and his hometown no longer feels like home. As the Bay Boys physically torment Cage, his mental wellbeing deteriorates. The Bay Boys’ manipulation brings about mind games that cause the Surfer’s reality to become more are more blurred.

Plagued by the extreme Australian heat, a visual haze persists throughout The Surfer. Ladczuk strategically uses the sun as did Quaid for transitions, symbolizing both the fading nature of time in the The Surfer and the life of its protagonist. Reluctant to move on, the Surfer’s emotions begin to outweigh his reason and his point of view quickly becomes more and more unreliable. Even the natural surroundings seem to be against Cage’s Surfer. Kookaburra calls align with the Bay Boys’ sinister laughter, mocking the Surfer’s every move. Kangaroos are also spotted in The Surfer, though fortunately none were harmed in the making of the film (unlike the brutal hunting sequence from Wake in Fright). Seeing Cage sleuthing around the beach like a bumbling detective, set to the tune of François Tétaz’s score, stands as one of The Surfer’s highlights. Tétaz’s work sounds similar to The Exotic Moods of Les Baxter whose music was borrowed for Inherent Vice (2014). The Surfer’s attempt to decipher the Bay Boys’ bizarre way of life allows for a crafty plot device that brings about memorable moments of confrontation. These skirmishes become increasingly outrageous over time, and their inclusion will appease the cult of Cage.

Though thematically and visually similar to The Swimmer, The Surfer’s script, written by Thomas Martin, does not quite pack the same punch as Eleanor Perry’s adaptation of John Cheever’s short story. Undoubtedly a tough act to follow in the footsteps of The Swimmer, The Surfer’s similar exploration of, denial, wistfulness, and the clannishness of society still makes for a worthwhile watch. The Surfer’s opening line “you can’t stop a wave. It’s pure anarchy… You either surf it, or you get wiped out,” best summarizes the film. Like John Milius’ Big Wednesday (1978), The Surfer uses surfing as an analogy for life itself. Like waves, life presents its obstacles. Some are bigger than others, and their cadence is unpredictable. The Surfer concerns itself with the waves of life and their impact on the ill-fated men who can’t seem to escape them. Finnegan navigates the waters of filmmaking well enough to avoid a wipe out of his own, and The Surfer serves as another notable entry in the director’s catalogue as a continuously growing indie auteur.

The Surfer is now exclusively in theaters via Roadside Attractions.

Jonathan Monovich is a Chicago-based writer and a regular contributor for Film International. His writing has also been featured in Film Matters, Bright Lights Film Journal, and PopMatters.