By William Blick.

The country’s journalists – local or national – are working for all of us. They are our soldiers. And we need to support them.”

Rick Goldsmith’s Stripped for Parts: American Journalism on the Brink is the third installment in a trilogy of documentaries by Goldsmith about American journalism. It appears that something ominous is occurring to local and daily newspapers across the country. They are disappearing! Jobs in local journalism also seem to be evaporating. In fact, the subject of this film is the revelation that an elusive hedge fund is buying up all the local newspapers to turn a profit. Goldsmith brings into focus investigative journalists who challenge “vulture” investment practices, or the buying and dismantling of distressed businesses, in this case local newspapers across the United States. Goldsmith goes in depth with a few journalists who are fighting back against these actions, which are perceived as damaging attacks to the freedom of the press and the future of democracy in America.

Goldsmith is most known for his Oscar-nominated documentary, The Most Dangerous Man in America (2009) regarding the top-secret Pentagon Papers which were uncovered by Daniel Ellsberg. These papers were published in The New York Times in 1971, revealing that several presidential administrations withheld essential information or provided misinformation about the Vietnam War. The title of the film comes from a phrase that Henry Kissinger said referring to Ellsberg.

Journalism has always been a staple of American democracy. Dating back to the American War for Independence, newspapers have served democracy faithfully in America. Local journalism is essential for information needs on many levels. It keeps communities aware of issues that directly affect them, and it holds local businesses, services, and authorities accountable to people they serve and keeps them transparent. Goldsmith explores this detrimental threat to one of the basic core tenets of American values, freedom of the press, and shows the bravery of people determined to defend the information needs of our communities.

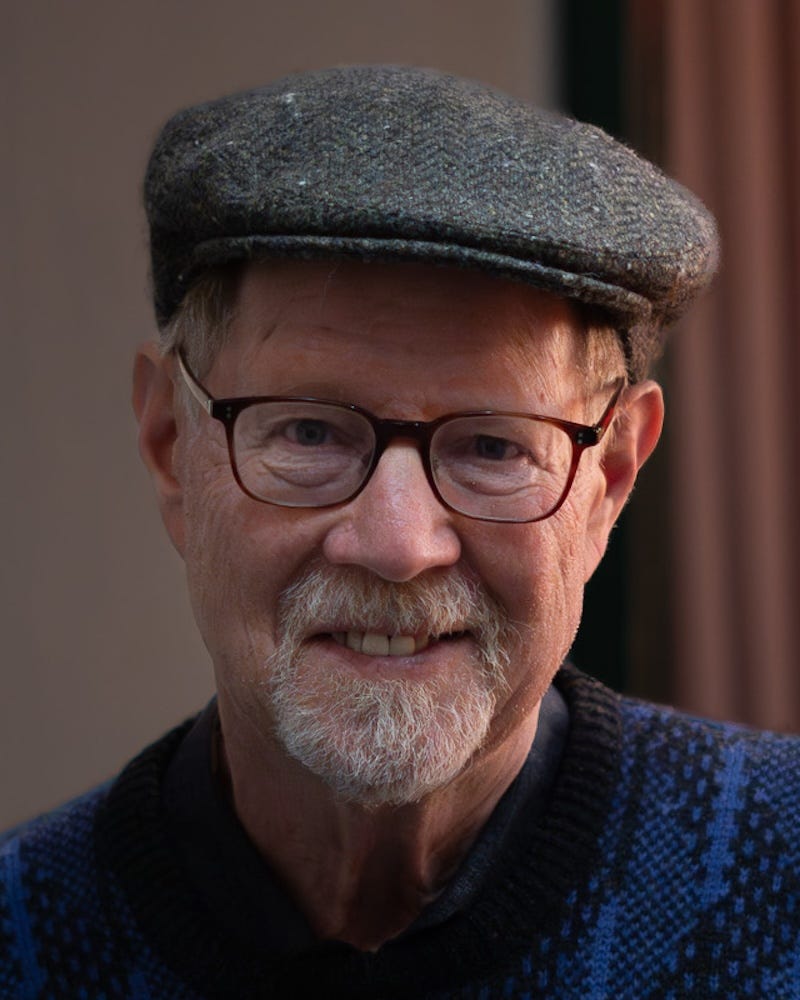

I spoke via Zoom with Goldsmith regarding the Stripped for Parts (currently streaming for free at PBS.org).

This film is part of a trilogy of films you’ve made on journalism. What interests you in journalism? Why is it so essential to American democracy?

I’ve been a news junky since I was a kid. It connects you with the world. It makes you understand that there is a bigger thing out there than just your little bubble.

The journalists that I know are all amazing people. They look at things from all sides. They tend to be succinct and they’re world-wise people. They have good bullshit detectors, and they know when something’s off. So you feel like you’re getting the truth from journalists, even if you’re making a film on a different subject.

In other words, some of my films focus on journalism, but even if you just bring in journalists to help tell a story, they do a good job telling the story…and especially at this moment of time. We are in a country where we are on the verge of possibly losing democracy. We have a drive towards authoritarianism. The word, the phrase, the Fourth Estate, is supposed to imply that. While there may be three arms of government executive, legislative, and judiciary, the fourth piece is the press, and they’re holding the others accountable. They’re holding people in power accountable. And that’s what’s so good about them, and that’s what’s so valuable about them for democracy.

I read in another interview that political filmmakers such as Costa-Gavras and the films of Alan Pakula were some of your influences. I was wondering what some of your favorite films are.

Wow. What’s my favorite film? I like films about journalism. I mean, I love All the President’s Men. I love Spotlight. I love some of the old films with Jimmy Stewart or Bogart and Ace in the Hole with Kirk Douglas. They’re juicy and they’re about something. What is great about journalism is there’s always a story. There’s always a conflict. You have two sides, and you’re rooting for one side or the other, or you just rooting for the truth. I also like some of the classics like Casablanca and The Godfather.

How would you describe your approach to a documentary? What do you need to know? Why do you choose the material you choose?

Well, I think my approach is very journalistic and that’s not necessarily common among documentary filmmakers. Some of them are. Some of them are not, but I feel like I adhere to a lot of the rules and the ethics of journalism. The same ones that your best reporters and your best editors and your best newspaper men adhere to. And I think that I tell stories with visual and audio much the way journalists tell stories. In that, I focus on the personal because when you focus on the personal, it connects you with the audience. But it’s not necessarily just about a person or a person’s journey. It’s a bigger issue. My films tend to be personal stories that address social issues.

Or “muckraking”?

Yes, some of them are muckraking. The first feature film was one of those films in my trilogy. Tell the Truth and Run about George Seldes, and the American press. Not many people in our generation know who George Seldes was, but he was a giant among the Muckrakers, independent journalists, and press critics. He was like the leading press critic of the 20th century. And his career goes back to the beginning of the 20th century. World War I, and Europe and Mussolini and Lenin. He was just an amazing person with amazing tales to tell.

So let’s talk about Stripped for Parts, your new film, and the newspaper industry. The local daily newspapers are disappearing, and in fact it is this hedge fund that is buying them up. How did you come across this story?

I was pointed to the story by Bill Moyers. I had been talking with Bill Moyers. He was a great broadcast journalist who just died in June. He knew my work, and I knew his work. I approached him to do a film on him, but he didn’t want to be the focus of a film. So we did toss back some ideas on what a good film might be, and nothing really clicked, and I thought that was the end of it. And then a few weeks later, when I thought my conversations with him were over, I get an email from him, and he says, “I’m sitting in the barber’s chair, and I’m reading this story, and I said, “This is a film that has to be made and Goldsmith’s the one to do it.” And he points me to this article, which you see at the beginning of the film. The headline of the article is Alden Global Capital is making so much money wrecking local journalism that it may not stop anytime soon.

What that story told was about this Denver rebellion that you see partway through the film of these editorials that were written in the Denver Post blasting, the hedge funds. And then they go on the picket line in Denver first and then a week later in New York and the headquarters of Alden Global Capital.

So it was a great story because it had a conflict. That’s what you want. It had journalists telling a story, I love journalists, so that’s who I knew I was going to interview. But more than that, the journalists were doing something unusual. They were becoming part of the story. Usually, they’re taught, you don’t report on your own industry. You don’t report on your own profession. But they were reporting on their own their own profession and their own industry and the journalism that was dying.

And why is this important at this point in time?

Well, I knew that the newspapers that I was getting were thinner, But I didn’t really know why. And so they were, as I said in my film, “the canaries in the coal mine.” They were letting the audience know what was happening from this predatory vulture capitalist outfit.

There was another step in the decline of journalism. Somebody actively wanted to feed off the carcass and make money without concern to the effects on the community.

And what do you think the local newspapers contribute to the community? I know that they make their public services accountable, they make the businesses transparent, and they keep their public informed.

I think they do a lot of things. They keep the community together because it’s like a focal point in different parts of the community that might not mix. You know whether it’s even through the arts or high school sports or whatever, the newspaper has traditionally been the one institution that knits the community together.

But I want to go one step further. Their most valuable aspect is their watchdog role, so they are looking at abuse of power. They are looking at whether it’s people in government or crooked sheriff or maybe there’s a company that’s dumping their waste into the river and polluting the water as Greg Moore says at the beginning of the film. There was nobody watching Flint, Michigan. And when you have vibrant newspapers, or let’s say when you lose newspapers, corruption goes up. Voting goes down. Right. People don’t know what’s going on in their community. Taxes go up because the insurance cost goes up. Now, that’s counterintuitive. Why would the insurance for the city go up? Well, because studies have shown that when the newspapers disappear, corruption does go up and the city is at risk more from lawsuits, from police misconduct, from whatever. So, we really can’t have a vibrant democracy if there’s not vibrant journalism in every city, town, or outpost in this country.

So, what has been your greatest challenge as a filmmaker, as a documentarian?

My biggest challenge as a filmmaker is to come up with the material. What do I want to do a film about and all of the films that I’ve done throughout my career? They’ve been films that I’ve initiated, just because I keep my eyes open and I say, what is important, what makes a good story? You know, nobody has come to me to say, “I want, well, that’s not true. People have come to me to say, “What do I want to do a film about?” But the films that I really latch onto are the ones that I initiate. And they’re the ones that I feel are stories that will make good filmmaking. In other words, they’ll engage the viewer, but also that they’re about something that’s meaningful. They are about a social issue that we need to pay attention to.

I made a film about a basketball player named Chamique Holdsclaw. She was called the female Michael Jordan and she was struggling with mental illness. She had started to come out about it. I said, this is mental illness and it’s a big issue, and it’s largely hidden. People don’t want to talk about it. People have mental illness in their family. They don’t want to talk about it. And this was bringing things out in the open.

So I think that you’re most known for your Oscar-nominated film. The Most Dangerous Man in America, the story of Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers. Can you describe briefly what that experience was like when you were nominated for an Oscar?

I was nominated twice; I was nominated for Tell the Truth and Run as well. So that was my dress rehearsal for my second nomination. It’s fun and it’s crazy making. It’s fun because you want your film to get known out there. You look at all the documentary films that have ever been made in this country or other countries. And very, very few of them have a large audience. You know, if you had mentioned most of my films, except for maybe that one, people would never have heard of most of the films.

When you get nominated for an Academy Award people hear about your film, they come out to see your film. Your film is more likely to be in the theaters. It’s more likely to be on television. And that’s the whole purpose of making films. You don’t do films for your 100 closest friends. You make films for thousands. That is why you do the films. So it’s on that stage that you can maybe make a difference. So, you know, I smile when people ask me about the nominations for Academy Awards, because part of me feels like it’s just an award. And it’s just a nomination. It’s just your peers. It’s really a peers’ award, even though it reaches a billion people every year. The ceremony does. But it is a high.

While we’re on the subject of the Ellsberg documentary – a person who risked life and limb to bring the truth to the American public. What would you say is the greatest threat to American democracy right now?

The biggest threat to democracy: the guy sitting in the Oval Office. And that is why journalism is especially important today. The press, the Fourth Estate, is on the front lines. They have got to do their job in holding this President and his political supporters to account, to expose their lies and misrepresentations, to not be cowed by his threats, bullying and intimidation, as, disturbingly, too many of the established legacy news organizations – Washington Post, CBS, ABC – have started to succumb, to protect corporate interests or billionaires pocketbooks. The country’s journalists – local or national – are working for all of us. They are our soldiers. And we need to support them. The country is at a crossroads. At stake is our very democracy. (And so says Greg Moore, in the first scene of my film, after the introductory set-up.)

Stripped for Parts: American Journalism on the Brink is available for streaming free-on-demand, on PBS.org until December 31st, and will be broadcast on PBS-affiliates across the country. See a full list of broadcasts at strippedforpartsfilm.com.

William Blick is a literary/crime fiction and film critic, a librarian, and an academic scholar. He is contributing editor to Retreats from Oblivion: The Journal of Noircon and has published work in Senses of Cinema, Film Threat, Cinema Retro, Cineaction, and Film International Online, where he frequently contributes. He is also an Associate Professor/Librarian for Queensborough Community College of CUNY.