A Book Review Essay by Johannes Schönherr.

German scholar Marie Sophie Beckmann discusses inherent contradictions of the ‘spilling’ of the films into other art forms as well as the ‘spilling’ of the films as ‘contained’ entities (films on video) to a worldwide audience in detail.'”

When Nick Zedd, the mastermind of New York’s “Cinema of Transgression,” died in February 2022 at the age of 63, the mainstream New York City press remained absolutely silent. There was no obit in the New York Times, and the New York Post didn’t use the opportunity to throw out some salacious stories. The professional film press also remained mute. Variety, Hollywood Reporter, Deadline: nothing. The academic film publications stayed equally silent. “Censorship by omission,” Zedd would have called it, using the term he always liked to use when he felt getting ignored. (There was some noise regarding Zedd’s passing in social media, but it was Art Forum that published an obituary. Art Forum got what Zedd was all about.

The films produced by the loose bunch of filmmakers Zedd promoted as the Cinema of Transgression in the 1980s were never intended for commercial theatrical exhibition. They were screened at times at art house theaters, of course, but they originally were made to be shown in East Village punk rock clubs. In the intermissions between the concerts of rock bands, as part of multi-media shows, as part of art performances.

Cinema of Transgression works, with all their extremely violent and pornographic images, added a hitherto unseen radical edge to whatever the proceedings of the club night in question were. Daring shock visuals with loud post-punk noise on the soundtrack, all captured on cheap Super 8 film.

Hollywood took notice. A number of scenes in Oliver Stone’s 1994 Natural Born Killers, for example, feel like taken straight out of Cinema of Transgression movies, including the Super 8 aesthetics, without giving any credit to the NYC underground filmmakers. Zedd complained bitterly about that commercialization of his radical approaches but to no

avail.

Times changed. Rents went up, clubs closed. The filmmakers involved in the Cinema of Transgression grew older and shed their drug habits which so often had fueled their visions while making their 1980s movies. By the early 1990s, the movement was history. Though today, the original Super 8 prints of the most influential of the Cinema of Transgression films (like Richard Kern’s Fingered [1986]) are part of the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

Cue in to German scholar Marie Sophie Beckmann. In her book Films That Spill – Beyond the Cinema of Transgression (Rutgers University Press, 2025) she starts out by describing her own introduction to the Cinema of Transgression, from a large 2012 Berlin art exhibition focused exclusively on the films of the loose 1980s filmmaker group. She’s fascinated by the many radical films projected in multi-media fashion at the exhibition but at the same time deeply concerned about the impact the KW Institute of Contemporary Art (which was closely linked to the Museum of Modern Art in New York) had on its very Berlin surroundings.

A museum displaying radical art as a gentrification force? The artists creating radical arts acting as agents of gentrification in the impoverished neighborhoods they move to because it’s exactly those neighborhoods that give them the opportunity to develop their art and to display it? It’s a recurring topic in Beckmann’s book, but also one that has been discussed for decades.

Much more interesting is Beckmann’s discussion of the titular “spilling” versus the containment of that spilling. Spilling meaning one art form spilling into another, i.e. film becoming integral parts of visual arts. performance art, etc. The containment on the other hand meaning the separation of the singular art forms, forcing them back into their traditional exhibition formats. With films in this case, that would be theatrical screenings.

Beckmann defines “spilling” in the introduction to her book:

The notion of spilling lends itself perfectly to such an endeavor. It evokes associations with fluidity, transmission, disorder, and randomness. As such, it has little to do with the solid materiality that we usually ascribe to technical media in general and to film in particular, which is precisely why it can be used to conceive of film as a messy object that we encounter in temporary, often surprising formations and unexpected places, characterized, for instance, by its mobility and mutability.”

But then, in their contained form, as curated theatrical art house screenings, the works of the Cinema of Transgression had their biggest international impact. Taken from their immediate context, the films became provocative representations of the New York underground and its excesses and as such were violently attacked by radical feminists in Berlin, Nuremberg, Mainz and other places, causing scandals and resulting in press coverage that would greatly enhance the films’ popularity among viewers both in Europe as well as back in the U.S.

Masked girls dressed in black leather throwing paint at the screen? Talk about “spilling” obscure Super 8 flicks into the center of public attention, video release deals closely following.

In fact, VHS video (and later DVD) became the format in which the films of the Cinema of Transgression reached their widest audiences. Video compilations curated by Nick Zedd (1985), by film institutions like the British Film Institute (2000) or by individual filmmakers like Richard Kern, were released worldwide. Those videos, though separated from the original cultural environs of New York’s underground clubs, would have a strong impact on audiences and aspiring film directors alike, in Japan, in Europe, as well as across the U.S.

Beckmann discusses those inherent contradictions of the “spilling” of the films into other art forms as well as the “spilling” of the films as “contained” entities (films on video) to a worldwide audience in detail. She also clearly points out that the Cinema of Transgression was not the first filmic “movement” facing those contradictions.

The New American Cinema of the 1960s, the “experimental / underground” films promoted by Jonas Mekas and showcased at New York’s Anthology Film Archives, faced similar contradictions. When presented at, say, the then-only festival for experimental cinema in Knokke, Belgium, the American films would be perceived by the European audience in quite another way than they would be back in New York where they originated from.

Nick Zedd himself had a very conflicted attitude towards the New American Cinema. He absolutely glorified some of their films, especially the works of Kenneth Anger (Scorpio Rising, 1963), Jack Smith (Flaming Creatures, 1963) as well as some of the works of the Kuchar brothers like George Kuchar’s Hold Me While I’m Naked (1966). He had however no tolerance whatsoever for the structural works experimental film directors produced once they had gotten established and been given university teaching positions.

In 1979, Zedd had released a punk rock Super 8 trash epic titled They Eat Scum. Those were the times of the No Wave Cinema, of no-budget filmmakers like Beth B, Amos Poe, Eric Mitchell and a young, aspiring Jim Jarmusch working closely with their musician friends, producing disturbing yet stylish pieces clearly influenced by the French Nouvelle Vague of the 1950s.

Zedd’s trash epic clearly had no place in that cinema. Village Voice critic Amy Taubin labeled the film transgressive in one of the very few reviews published at the time. Zedd took note of the term. Waiting for a few more years, Zedd eventually discovered likeminded filmmakers with radical punk roots – in his very own neighborhood, the Lower East Side / East Village of New York.

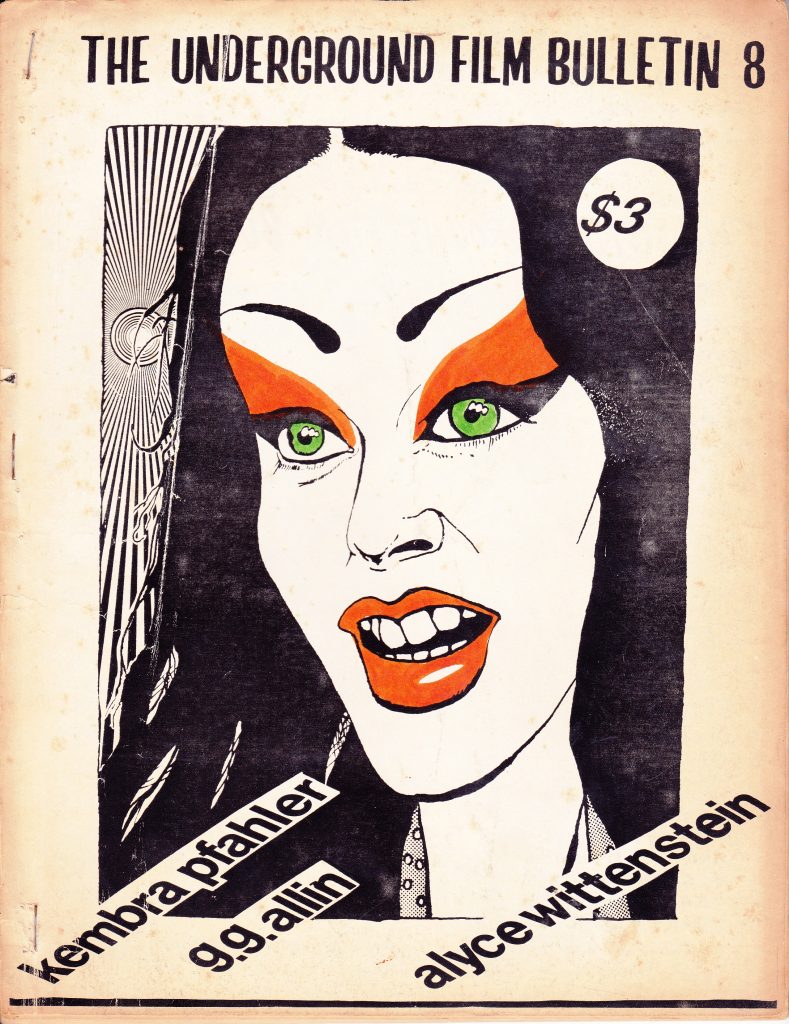

In 1984, Zedd launched his own fanzine, the Underground Film Bulletin, promoting the films of his newfound friends as well as his own. Nick Zedd’s birth name was James Harding, Nick Zedd was his filmmaker alias. The fanzine, however, he published under the name Orion Jeriko, his second alias. That way, he could easily promote and even interview himself without the fact being too obvious.

Zedd himself had a very conflicted attitude towards the New American Cinema. He absolutely glorified Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and the works of the Kuchar brothers… [though Zedd] had no tolerance whatsoever for the structural works experimental film directors produced once they had gotten established and been given university teaching positions.”

The Underground Film Bulletin, was completely published as b/w photocopy with only a few color felt pen strokes made personally by Zedd on each individual copy highlighting certain features of the cover character. As Beckmann points out, the Underground Film Bulletin was clearly a poor man’s copy of Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine. The intention was the same: just as Warhol promoted his friends, associates and self-declared “super stars” on the glossy pages of Interview, Zedd promoted himself, his friends and the people he considered his “stars” in the Underground Film Bulletin.

Sold with a good portion of cheeky humor, (“collector’s item / good for swatting flies”) the Underground Film Bulletin soon found a readership. In issue #4 (1985), Zedd eventually published his Manifesto of the Cinema of Transgression, an aggressive statement delineating his concrete ideas. Much in the tradition of manifestos of previous artist movements, i.e. the Dadaists. The manifesto doesn’t mention commercial cinema at all and goes straight to claiming the heritage of the American underground of the 1960s which Zedd considered to have been stolen by the institutionalized academic avant-garde:

We who have violated the laws, commands and duties of the avant-garde; i.e. to bore, tranquilize and obfuscate through a fluke process dictated by practical convenience stand guilty as charged. We openly renounce and reject the entrenched academic snobbery which erected a monument to laziness known as structuralism and proceeded to lock out those filmmakers who possessed the vision to see through this charade.

We refuse to take their easy approach to cinematic creativity; an approach which ruined the underground of the sixties when the scourge of the film school took over.

….

We propose that a sense of humor is an essential element discarded by the doddering academics and further, that any film which doesn’t shock isn’t worth looking at. All values must be challenged. Nothing is sacred. Everything must be questioned and reassessed in order to free our minds from the faith of tradition. Intellectual growth demands that risks be taken and changes occur in political, sexual and aesthetic alignments no matter who disapproves. We propose to go beyond all limits set or prescribed by taste, morality or any other traditional value system shackling the minds of men.

In the manifesto Zedd also makes clear who belongs to his envisioned Cinema of Transgression. Namely, Zedd himself, Richard Kern, Tommy Turner, Richard Kleeman, Manuel DeLanda, Bradley Eros & Alina Mare (Erotic Psyche) and DirectArt Ltd.

All of them being heterosexual white rebels with an educated middle-class background.

In fact, that composition of the original members of the Cinema of Transgression as declared by Zedd became the ‘groups” most important asset.

Here was suddenly a bunch of radical punk-porn underground folks rooted in the old underground but with their films devoid of the gay aesthetics the classics by Kenneth Anger and Jack Smith featured.

In the movies Zedd praised as Cinema of Transgression, there were suddenly cocks and cunts with a strong desire to interact in whatever twisted way. More often than not quite explicitly so.

Underground film aesthetics finally met up with punk rock and straight male sensibilities. Reaching audiences that would not at all be attracted by anything gay on screen.

David Wojnarowicz, the famous gay artist and AIDS activist, is often mentioned in connection with the Cinema of Transgression. In fact, as famous as he was elsewhere in the art / gay scene, in terms of the Cinema of Transgression, he was a minor character. Still, he was an iconic actor in Richard Kern’s Stray Dogs (1985) and You Killed Me First (1985).

Women on the other hand, were a very strong force in the Cinema of Transgression. First of all, there was Lydia Lunch, singer in the post-punk band Teenage Jesus and the Jerks, actress in various No Wave film productions, spoken word performer. Lunch wrote the screenplays for two of the most iconic Cinema of Transgression movies and acted in them as the main character a well, in The Right Side of My Brain (1985) and Fingered (1986), both directed by Richard Kern.

Then there was actress Lung Leg, there was filmmaker Casandra Stark, there was filmmaker Kembra Pfahler who was also the singer in underground band Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black, usually performing in the nude, just covered with body paint.

Of particular importance was the New York Film Festival Downtown, starting in 1984 and taking place annually until 1989, which Beckmann covers the festival in great detail. The festival, held in the East Village was organized by two well-connected outsiders: by Tessa Hughes-Freeland, a British transplant and by Cuban-American artist Ela Troyano.

The festival tried to present the whole range of the cinematic approaches of the Downtown art scene of its times. Ranging from slide shows by now famous artists like Kiki Smith and Nan Goldin to works that would soon be considered to belong to the Cinema of Transgression to Jack Smith presenting films in person.

“Anything goes”, was the approach. Unfinished works were fine and so were screenplay readings of films never made. There was performance art, there was stand-up comedy, there were concerts. It was a celebration of underground culture incorporating anything and everything considered to be worth included by Hughes-Freeland and Troyano.

On the other hand, European art house programmers quickly discovered the festival and took curated “best-of” programs across the Atlantic. Popularizing certain films over there… typically those of the Cinema of Transgression variety.

Tessa Hughes-Freeland and Ela Troyano became soon part of the Cinema of Transgression group themselves. Their joint project Playboy Voodoo was screened widely both in cinemas as well as in conjunction with festival appearances by noise jazz musician John Zorn in the 1990s. Tessa Hughes-Freeland could be called the last hold-out Cinema of Transgression filmmaker, making movies transgression-style well into the 1990s.

Ela Troyano on the other hand was officially expunged from the group by Nick Zedd already in the mid-1980s. Zedd disliked her directorial style … and yes, he did at times behave like a dictator who owned the Cinema of Transgression.

Today, some of the films of the Cinema of Transgression are still in wide circulation, especially the films of Richard Kern aged very well and are now considered classics. Kern himself is today an established photographer. Most of the other films, including Zedd’s have rather become time capsule style obscurities of a long gone past. The times of a vibrant, dirty Lower East Side with low rents and a drug-fueled punk-inspired radical arts scene.

As exciting and stimulating as Beckmann’s discussions of all those events and the resulting shifting perspectives are, be aware… Films that Spill is in no way an easy introduction to the Cinema of Transgression. The book is advanced reading, aimed at readers already familiar with the core works of the loose group.

As the book’s title indicates, the book focuses on the structural fluidity of the scene creating the films as determined by economic factors (those rising rents and shifty landlords) and the general cultural climate with a special focus on the complicated spill-over effects of their works into the wider art world and beyond.

Despite all its candid discussions of the original nightclub screenings in the East Village back in the 1980s, however, the book provides almost no information on the biographical background of the filmmakers involved, neither does it provide any close-up discussions of the core films.

So, if you are not thoroughly acquainted with the works of the Cinema of Transgression, prepare yourself by watching some of the films before opening the book. Watching Angélique Bosio’s 2007 documentary on the Cinema of Transgression, Llik Your Idols would give you a good start.

To get more acquainted with the personal histories and viewpoints of the filmmakers themselves, Jack Sargeant’s 1995 book Deathtripping: The Cinema of Transgression would make for a great companion piece to read alongside or in preparation for Beckmann’s book. (Sargeant’s book has been re-published as Deathtripping: Underground Trash Cinema in 2007.)

Johannes Schönherr is the author of Trashfilm Roadshows – Off the Beaten Track with Subversive Movies (Headpress, 2002) and North Korean Cinema – A History (McFarland, 2012).

Just to clarify, the New York Film Festival Downtown was not an “anything goes festival.” It was film-based and included expanded cinema. The “stand up comedy” referred to were performance artists who acted as master of ceremonies between segments. They also announced the content of the films. Thank you

I’m Monica Zedd widow of Nick Zedd, I was married to him for 15 years, I’m in charge of the preservation of his archive together with the fales library at NYU and I want to say he came with the term of CINEMA OF TRANSGRESSION, he always is the head of his movement, he is the one that show his films in europe tours since the 80s and gave the opportunity to other filmmakers to show their work since he wasn’t gritty taking their films with him to show them as well as his master pieces. he always show his work at museums, strange very underground places and when we move to México he continue doing films and really big grr8 paintings, animate his paintings and he is considered the king of underground since he did films as a teen and never stop producing new films until he die in my arms. long live the king Nick Zedd