By Jonathan Monovich.

When I do commentaries now, I find myself examining films on a more forensic level, responding to individual scenes and shots and taking them apart. My rule with commentaries is that I need to learn something, and I need to know more coming out then I did going in.”

—Tim Lucas

Tim Lucas has always treated physical media as cinema’s archive, dedicating his life to the study, preservation, and evolution of film. Lucas deserves recognition for his independence, enthusiasm, expertise, and, of course, talent. He was a true pioneer, paving the path for the scholarly consideration of video in the lexicon of film studies. From his early days at Video Times, Lucas earned the “Video Watchdog” moniker. He repurposed the badge of honor for his beloved, self-published magazine—Video Watchdog. A nearly thirty year venture with his late wife, Donna, Lucas’s Video Watchdog became known for its encyclopedic knowledge and discerning ability to decipher the differences between video and theatrical releases of films. Like his beginnings at Cinefantastique and Fangoria, Lucas forever documented a serious approach for fantastic films. Understanding that film was founded on the work of Georges Méliès, Lucas felt a responsibility to approach the subject matter with an intelligent, authorial vision. Lucas continued this philosophy with his monographs Videodrome: Studies in the Horror Film, Spirits of the Dead, and Succubus. Well-respected by Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino, Guillermo del Toro, Joe Dante, and Roger Corman, all contributed praise to Lucas’ most ambitious project—Mario Bava: All the Colors of the Dark. Chronicling Bava’s life in 1,000+ pages, Lucas’ self-published masterpiece took decades to materialize. Lucas also continues to be the world’s most prolific Blu-ray audio commentator, just shy of his 200th disc commentary, approaching his subject matter with methodical precision.

With Lucas’ life consumed by video, his debut novel, Throat Sprockets, naturally reflected on his love/hate relationship with the format. Throat Sprockets tells the tale of an unnamed advertising businessman’s descent into insanity, possessed by an unhealthy obsession with a mysterious film named “Throat Sprockets.” The splices in the botched film print send the Ad Man down a rabbit hole to discover the missing pieces. Out of print for decades, Valancourt Books has revived Throat Sprockets at a prescient time for its thirtieth anniversary. Lucas’ Throat Sprockets still excels in its satirical examination of cinephelia, advertising, and the vampire myth. Equipped with new material and an introduction by Tananarive Due, Throat Sprockets’ acknowledgment of detached humanity, declining theatrical moviegoing, and increasing censorship in the film industry feels even more relevant now. With horror films becoming increasingly self-aware of their role in society, Throat Sprockets also offers wise commentary on the relationship between horror films, wars, and the context in which they are made.

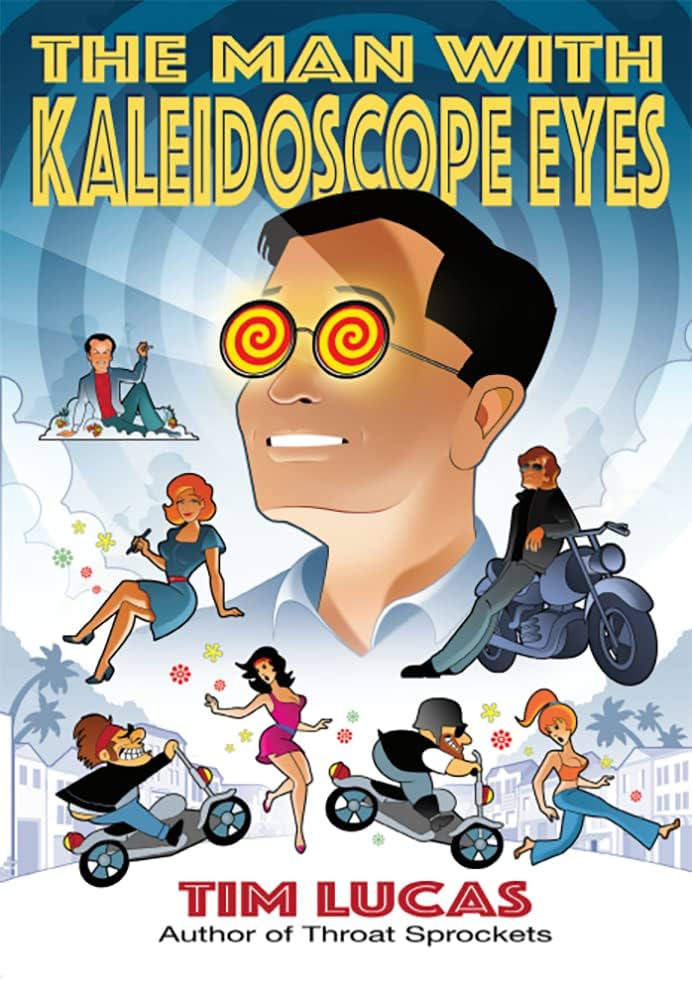

Lucas’ next novel, The Book of Renfield: A Gospel of Dracula, serves as a clever supplement to Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Lucas’s attention to vampiric mythology flows into BearManor Media’s collected film criticism from his blog in Pause. Rewind. Obsess. and his Sight and Sound column in No Zone. Lucas’ screenplay turned novel, The Man with Kaleidoscope Eyes, about the making of Roger Corman’s The Trip (1967), foregoes horror for comedy. By naturally including Roger/Julie Corman, Jack Nicholson, Peter Fonda, Peter Bogdanovich, Monte Hellman, Sam Arkoff, and Dennis Hopper into one story, it feels dreamlike how everything weaves together. Lucas’ book recognizes the power of film as a collaborative art form and the birth of New Hollywood.Lucas’ novella, The Secret Life of Love Songs, was originally intended for an anthology of fiction based on Nick Cave songs. The story follows a songwriter doing a lecture, punctuated by performances of songs he wrote. It is accompanied by a CD, adding music to Lucas’ diverse resume. Inspired by a sighting of a sinister-looking man outside Lucas’ house, his latest novel, The Only Criminal, and Wes Craven’s A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984) come from a similar source of autobiographical terror. Forty-seven years in the making, the novel’s concept is that all evil in the world is attributed to one being, deemed “The Only Criminal.” Psychologist Dr. Paul Vaguely specializes in the care of patients with near contact of the Only Criminal. When the supposed “Only Witness” to have actually seen the Only Criminal arrives at Vaguely’s ward, the Only Criminal inexplicably disappears. The Only Criminal offers an inventive take on the oldest story of all—good vs. evil—and serves as a melting pot of Lucas’ recurring themes.

I had the pleasure of speaking with Lucas, over Zoom, about his career and upcoming projects. Quick to notice my one sheet for Roger Corman’s The Young Racers (1963), Lucas proudly shared he has also had the poster on display in his office for several years.

Your beginnings as a writer at Cinefantastique, as a teenager, are similar to Cameron Crowe’s start at Rolling Stone. You both started so young. Have you considered writing a story, like Almost Famous (2000), about that time in your life?

Before Throat Sprockets, I wrote a half-dozen unpublished novels. The most ambitious was a 400+ manuscript called TV Heaven, which was based on that time in my life. I lived with a few friends in a $50 a month apartment, where we created the content for a Cincinnati entertainment newspaper called The Queen’s Jester. I reviewed films, albums, and concerts and got to hang out with various bands, so it was very close to Almost Famous. A highlight was watching The Fearless Vampire Killers (1967) in a Holiday Inn hotel room with Blue Öyster Cult!

While at Cinefantastique, you also were a correspondent on the set of David Cronenberg’s Videodrome (1983). What was that experience like?

It was an education. I’d met David on a Scanners (1981) junket and had written some advance pieces on Videodrome as it was getting underway. He offered me an exclusive invite to the set in Toronto. My first trip up was on what was supposed to be the last week of filming, but David simply didn’t have the right ending for Videodrome yet. This was in December 1981, right before Christmas, so post-production shooting continued the following March. In hindsight, I was shown complete trust and given incredible access to people, the script, and dailies. I went up again in 1983 to see the finished film. It was a great time in my life, and I made some lifelong friends.

You eventually published a book on Videodrome for Millipede Press’ Studies in the Horror Film series. Did you have to add much, or did you mostly repurpose preexisting unpublished material?

The book mostly consists what I wrote in the ‘80s, with added interviews conducted on the set. It’s out-of-print now and getting expensive, so an expanded new edition is being discussed.

In your commentary for the Videodrome Arrow Blu-Ray, you mention that when you and Cronenberg first met you connected through shared literary interest in William Burroughs. It’s not surprising you worked on Naked Lunch’s (1991) script as you both are clearly on a similar wavelength.

I worked on a script, but not the script. During this period, I was writing for Heavy Metal, and the editor of their “Dossier” section was Brad Balfour (my old roommate from the Queen’s Jester years). Brad had met Burroughs’ secretary, James Grauerholz, who told him that Burroughs really wanted to see a Naked Lunch film before he died. Burroughs felt that Cronenberg was the guy to do it. Brad knew of my Cronenberg connection and offered to put us in touch. At that time, David was pounding out scripts for Total Recall (1990), which he did not ultimately direct. He had done thirteen drafts and couldn’t meet the producers’ demands. So, when I offered to introduce him to Burroughs, he couldn’t jump aboard that at the time. In the interest of moving things forward, I asked if I might take a crack at writing a script, since I knew the novel well. Because he’s a mensch, David said “sure,” maybe thinking I wouldn’t come through, and I spent the next year writing two drafts. It wasn’t easy, but I spoke frequently with James, corresponded lightly with Burroughs (respecting his time), and got a signed copy of his new book, The Western Lands, as a thank you gift.

Once David was free, I sent him my second draft. He called and thanked me for my work, saying I’d saved him a lot of time and my script was helpful in alerting him to what would work and what wouldn’t. Ultimately, I hadn’t written the movie he wanted to make. This made sense to me, because of course, he would covet the opportunity to write the script of that “unfilmable” book he loved himself. One of the things my scripts proved was that you couldn’t make a Naked Lunch film solely from the book; you had to cull from the whole body of Burroughs’ work, especially the autobiographical Junkie and Queer. So, my scripts included things like the “William Tell incident,” which David incorporated into his film. He went on to win several awards for his vision. I never expected co-writing credit, as we had no contract, but it would have been nice to be acknowledged in the end credits, maybe in the fine print next to the beer provider. David did invite me to write a making-of book for a major publisher, but Donna and I were starting up Video Watchdog then and it was occupying all of my time. It supported us for the next 30 years, so it was the right decision.

Speaking of Cronenberg, I consider Throat Sprockets similar to Videodrome. Both grapple with how technology and media have altered our minds, bodies, and realities. How did the idea for Throat Sprockets come about, and do you also see a connection to Videodrome?

Throat Sprockets would never have come about without my friend Stephen R. Bissette, who invited me to write something for a new horror comics anthology he was preparing, called Taboo. His only guideline was that the stories had to break some kind of taboo. I don’t know where the idea came from; it was not something I was carrying around inside me, eager to burst out. I remember walking into my living room one afternoon. MTV was on the television, and pencils of light were coming through the Venetian blinds as in a film noir movie. As I passed through the light, the idea was suddenly there.

The taboo I settled on was penetration of the bite, which is something that even the most realistic vampire books and films had never really explored. The psychology behind the act of biting is akin to nursing, really; it’s about the giving and taking of warm nourishment from another body. It’s the most appalling thing you can imagine, biting someone to access their blood, but it mirrors the most wholesome thing in the world. I could see how “sprocketing” might become a kind of foreplay between couples or even the entire point of their intimacy. I had the idea that a guy in advertising, who had reached a kind of endgame in his own love life, would be exposed to a movie about this kind of behavior to the point where it would not only affect his life and his marriage, but also his work – which would be seen by everyone in America. So, the story is not just a taboo, but it’s also a satire about the world of advertising. It’s set in a fictional Midwestern city called Friendship.

As for Videodrome connections, I was on the set for two weeks and spent three years of my life writing its production history, so it was a major event in my life – not just a film I’d seen. You also need to consider the facts of my own life. From 1985 to 1988, I had been writing reviews and books for Video Movies/Video Times, a monthly magazine. Each week I received boxes of new horror films to review, and I was being exposed regularly to extreme material in movies that went beyond what I was used to seeing. As with Cronenberg and Videodrome, I was writing about me and taking the facts of my life in fantastic directions.

My assumption is that the mysterious director in Throat Sprockets is based on Jess Franco. You’ve studied Franco at great length throughout your career, dating back to the premiere issue of Video Watchdog. Is there any validity to my assumption?

Your assumption is on target. This is not present in the graphic novel chapters. I was only beginning to learn about those films at that time. By the time I’d embarked on my traditional novel version of Throat Sprockets, I was also writing “How To Read a Franco Film” for Video Watchdog and exploring Franco’s work and mythos deeply.

People have called (my book on Mario Bava) my masterpiece, but just as much (if not more), it’s Donna’s masterpiece. She spent four and a half years designing and realizing that book; it took her six months to assemble the index, as I kept adding to it.”

Is the new material for Throat Sprockets something you recently wrote, or have you been working on this over the years?

It’s all new but I always had this chapter in mind. Even the title, “The World Cotillion,” has been kicking around in my head since the 1970s. There’s a gap before the end of the book, in the previous edition. The story reaches a climax while the protagonist is still in his thirties, and then suddenly, in the final chapter, he’s a man in his sixties in Barcelona. That finale is based on a dream I’d had many years before. It was always my plan to use that penultimate gap to continue advancing the story in new editions, maybe once every decade, which would allow me to advance the story and its terrors while also exploring the latest advances or changes in the way we watch movies. Because, to me, the heart of the novel is the way it charts the decay of moviegoing as it used to be and how withdrawn and private it has become. The more withdrawn people become, the more license they have to pursue their darkest obsessions in secrecy. But those new editions never happened, so those chapters never got written until Valancourt Books expressed an interest in bringing the novel back into print. After putting it off till the very last moment, I wrote the new novella-length chapter—between projects—in a month. It fills in the details of the missing thirty years of the Ad Man’s life, chronicling how his obsession evolves with the advent of LaserDiscs, DVDs, Blu-rays, 4K and, of course, the internet.

In Throat Sprockets you mention how certain films have the power to transform someone into a different person. It’s my understanding that Spirits of the Dead (1968), Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), and Videodrome were the films that forever changed you. Are there other standouts?

Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (1961) is one of my favorites. It was written by Alain Robbe-Grillet, possibly my favorite novelist. I was fortunate to do commentaries for a Alain Robbe-Grillet BFI box set. Everything I’ve seen by Krzysztof Kieślowski has felt transformative to me. Seeing the whole Three Colors Trilogy (1993-1994) at a repertory theater was one of the most delightful days I ever spent. And Jess Franco, of course, though now that I’ve seen most of his work and most of my questions have been answered, my ardor has lost some intensity.

Throat Sprockets’ narrative is rich in its referential qualities, like the writing of Bret Easton Ellis, who supported the novel upon its initial release. For example, you include nods to the Beach Boys, André Bazin, Blue Hawaii (1961), the Doors, Georges Méliès, Shakespeare, and Rope (1948). What inspired you to include these eclectic references?

While writing Throat Sprockets, I listened to a homemade mix-tape that included tracks by the Beach Boys, the Doors, and other artists whose songs transported me to that particular world. I played that tape till it snapped. I applied for permission to quote certain lyrics but never received any responses, so I had to find clever ways of representing them in other ways. I found it’s actually better to describe music than to quote it. In the book’s new expanded version, the Ad Man’s latest musical touchstone is Neil Young’s “Cortez the Killer.” It’s a song that’s always haunted me. When I hear “Cortez the Killer,” I’ve always visualized a man listening to it on a car radio, while driving at night, with his head outside his window and the wind hitting his face and combing through his hair. Now, I know why.

Do you still have interest in adapting Throat Sprockets for the screen?

If it happens, it happens. In late 2010, I had the opportunity to write and direct a trailer for Throat Sprockets, as well as a somewhat revised scene from it, as a teaching exercise at the Douglas Education Center in Monessen, PA. That experience taught me the extraordinary value of a talented crew and proved me a resourceful and efficient director. I wish it had led to something; at the same time, I’m glad it didn’t. I’m going to be 70 next year, and I don’t have the physical drive to hustle. A talented and busy Belgian director, Jonas Govaerts, is interested in directing a film of it. I was recently approached by a British producer who then changed his mind. If someone had grabbed the novel when it was new, or when the graphic novel was being serialized, it would have anticipated The Ring (2002).

It surprises me that The Man with Kaleidoscope Eyes was never made into a film. Did you consult with Roger Corman, or any of the other characters, when you were writing the novel?

Not while I was writing the screenplay. I wrote the early drafts with Video Watchdog cover designer Charlie Largent. I was feeling lonely and wanted to speed things along, so I wanted a co-writer. We played e-mail ping pong between issues of Video Watchdog and finished the first draft in just twelve days. I wrote the novel independently, but some of Charlie’s dialogue and ideas are still present. He put the first draft in an envelope and left it on Joe Dante’s porch. He came home late after working on Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003)and stayed up late, unable to put the script down. I asked if he’d like to direct it, and he said he would love to.

About two days after Joe read it, I received a call from Roger himself. I’d never spoken to him before. This was the guy whose name onscreen taught me, as a kid, that “director” meant “storyteller.” He got a kick out of the project and told me that I had his blessing to take it as far as it could go. I later got to meet and spend time with him, even interviewing him over two nights before sold-out crowds at the St. Louis Film Festival’s “Vincentennial,” Vincent Price celebration, back in 2011. I also got to know, by telephone and emails, his longtime assistant Frances Doel, who sadly passed away last year. She admired the book and was never anything but supportive. Peter Bogdanovich, who is one of the characters, attended the Vista Theater’s table reading of the script, which starred Bill Hader as Corman, and I have photographic evidence that he gave the performance a standing ovation. I thought for sure the film was going to get made after that—they turned away as many people as they let in—but it still didn’t happen. Fingers crossed that someday it will.

I hope so too. Quentin Tarantino based a chapter of his Once Upon a Time in Hollywood novelization on your writing and proclaimed Mario Bava: All the Colors of the Dark to be “the greatest book on films ever written” in ll Fatto Quotidiano. How did you first meet Tarantino?

I’ve actually never met him. I was invited to his studio for the critics roundtable on his “Tarantino XX” 20th anniversary Blu-ray box set. It was an honor to be there with Elvis Mitchell, Stephanie Zacharek and the other critics, but Quentin wasn’t around. He was a Video Watchdog subscriber and has said some very nice things about me. We’ve exchanged emails, and I once interviewed him by phone for a French magazine about his fifty favorite movie sequels. They ran a condensed version. Then, we ran the full interview in Video Watchdog and both won Rondo Awards. When articles appeared in which Tarantino said he wanted his tenth and final movie to be a horror film, I wrote suggesting Throat Sprockets, which I think would be ideal for him… but—like Cronenberg—it’s got to be something he writes himself.

I haven’t asked much about the Bava book because it’s your most famous. Given how impressive it is, do you have any interest in republishing? I’m sure a lot of people would like to add it to their collection.

I’d love for it to be available and in a way that people can more comfortably read, but it needs to be done in a way that would not diminish what Donna brought to the book. People have called it my masterpiece, but just as much (if not more), it’s Donna’s masterpiece. She spent four and a half years designing and realizing that book; it took her six months to assemble the index, as I kept adding to it. The problem is that there are things that need correcting, updating and so forth, and anything done to the text is likely to affect Donna’s layout. It will be a delicate procedure, so I’ll likely have to stop doing commentaries for awhile to tangle with it.

Notably, the Bava book took over thirty years to write. In the afterword for The Only Criminal, you mention the long forty-seven year journey of the book getting published. How do these time lengths compare to your other books?

Throat Sprockets was accepted in 1991-2 and didn’t come out until 1994 because Dell decided to found Cutting Edge, a new imprint more tailored to it. The Book of Renfield was first written as a 50-page sample chapter and outline, and my agent wasn’t able to place it for ten years. I got my advance and picked up where I left off, as if no time had passed. The Secret Life of Love Songs is my shortest book, less than a hundred pages, yet it took ten years to perfect. After I turned in The Secret Life of Love Songs to PS Publishing, Dorothy Moskowitz, the former lead singer of the band, United States of America, and I decided to turn my novella’s verses into actual love songs and include them on a limited edition CD. This pushed the publication date back another four years. My new monograph on Jess Franco’s Succubus took four years to come out through no fault of my own.

Some may find The Secret Life of Love Songs uncharacteristic, but there are elements of romance and love in a lot of your work. Your dedication to Donna in the opening of The Only Criminal is also quite moving.

Thank you – and that dedication was written long ago, and she was familiar with it; I didn’t change a word of it after her passing. Decades ago, I was given a reading for a birthday present – sent to me on a cassette I still have – that told me I was going to have a hard life, which I would needlessly make harder on myself, but that I would “know the perfection of human love”- and I did.

Maybe, for that reason, nothing’s more interesting to me than the special alchemy which occurs when two people meet. It’s what all my books are about, ultimately. Even Throat Sprockets is about a life-changing encounter, between a man and a film, which opens the door to many other fated meetings. When I say that love is the most important subject for me, I don’t mean a twitterpated, simplistic kind of love. I mean the wrenching, existential kind found in Dante Alighieri’s Vita Nuova, D.H. Lawrence’s The Rainbow and Women in Love, or Henri-Pierre Roché’s Jules and Jim. These are beautiful works, but also excruciating and full of insight into the exaltation and the torment involved.

In The Only Criminal’s afterword, you note that Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943)and Georges Franju’s films were influences. Can you expand on how they helped shape the concept of the book?

Shadow of a Doubt is set in an idealized small town and is about what seems to be a perfect family – in which an innocent young woman named Charlie idealizes an uncle who shares her name and turns out to be living a double life as a serial killer. There’s a dreamlike sense, pierced by implacable evil, that permeates Franju’s Judex (1963), in particular. It’s set in a kind of storybook world where a man in danger might be saved by a trapeze artist who serendipitously happens by in a circus wagon. All of Franju’s work is photographed in a misty, hard-to-describe way that is somehow outside reality, in a bubble, until something evil appears to pop it, and I was aiming for that in The Only Criminal. My world, I think, has a bit more humor than theirs.

You must have the record for doing the most audio commentaries. Are you able to share what’s next?

I’m just about to record my 193rd audio commentary, a new take on a Mario Bava film I last commented on in 2010. My most recent ones were for four Robert Hossein films, a couple of Hammer films, and Somewhere in Time (1980). I’m told I’ve done more than anybody, so why am I not listed in Guinness’ Book of World Records?

What are your thoughts on the future of film criticism?

To be truthful, I don’t read much film criticism these days. I just need to know what and who is recommending what, so I’ll scan a review, you might say – always online. After that, what’s important to me is seeing what I want to see and formulating my own opinion. So, I can’t say where film criticism is going for others. As for myself, when I do commentaries now, I find myself examining films on a more forensic level, responding to individual scenes and shots and taking them apart. My rule with commentaries is that I need to learn something, and I need to know more coming out then I did going in.

Jonathan Monovich is a Chicago-based writer and a regular contributor for Film International. His writing has also been featured in Film Matters, Bright Lights Film Journal, and PopMatters.