A Book Review by Tony Williams.

It is early evening watching on UK’s ITV channel, the only one of two that existed in those pre-cable days in an era resembling former Prime Minister John Major’s definition of an England comprising village greens, little old ladies sipping tea, and warm beer! While BBC TV often confined its imports to Amos n’ Andy (a 1951-53 series not as racist as some of its later detractors alleged), I Married Joan (1952-55), I Love Lucy (1951-57), The Range Rider (1951-53), Champion the Wonder Horse (1955-56), The Cisco Kid (1950-56), The Burns and Allen Show (1950-1958) and The Phil Silvers Show (1955-1959) so as not to overwhelm viewers with too much of an unacceptable deluge of bad American culture, the privately financed ITV then regional Television Wales and the West franchise offered more diverse American product, such as Wagon Train (1957-1965), Riverboat (1959-1961), M Squad (1957-1960), and Dangerous Assignment (1951-1952). Every episode of the last series used to open in a foggy noir atmosphere with a debonair middle-aged man dressed like a stage-door Johnny approaching the camera. He would lean against a lamp post. Then, suddenly a knife thrown off-screen would embed itself in the lamp post, dramatic music begin, and secret agent Steve Mitchell, would commence his next dangerous assignment!

The opening was unusual, to say the least, even without knowing anything about surrealism concerning the incongruity of a blade embedding itself in a non-wooden substance. With the actor’s name following on the credits and an opening scene where a man in a gray flannel suit, the Commissioner played by Herb Butterfield, sends him on his next mission, one was hooked. At the same time, I saw a trailer for Val Guest’s Quatermass II (1956) with the same actor – Brian Donlevy – featured in a film then denied to me due to the X-certificate banning all those under the age of 16 from witnessing what adults deemed unsuitable for young eyes! As time went on, I saw more of Donlevy either in the last features of his career or on UK television showings of his previous roles, such as the often silent heavy in Hawks’s Barbary Coast (1935) and Two Years Before the Mast (1946), with my first appreciation of the soon-to-be-blacklisted Howard Da Silva playing a brutal sea captain overshadowing its bland star Alan Ladd, and The Great McGinty (1940), to say nothing of his commanding performance as Sergeant Markoff in William Wellman’s Beau Geste (1939) that I first saw on a double bill at the National Film Theatre in 1974, alongside Ronald Colman’s silent 1926 version. Donlevy (1901-1972) was definitely an accomplished actor who often made distinctive impressions in his various screen roles during the height of his career. Today, outside classical Hollywood film circles, he is usually the subject of detrimental references on Facebook Quatermass sites with posters often siding with writer Nigel Kneale as to his unsuitability for the role, an attitude both unfair to the actor and unwilling to consider other important aspects of the production period.

The opening was unusual, to say the least, even without knowing anything about surrealism concerning the incongruity of a blade embedding itself in a non-wooden substance. With the actor’s name following on the credits and an opening scene where a man in a gray flannel suit, the Commissioner played by Herb Butterfield, sends him on his next mission, one was hooked. At the same time, I saw a trailer for Val Guest’s Quatermass II (1956) with the same actor – Brian Donlevy – featured in a film then denied to me due to the X-certificate banning all those under the age of 16 from witnessing what adults deemed unsuitable for young eyes! As time went on, I saw more of Donlevy either in the last features of his career or on UK television showings of his previous roles, such as the often silent heavy in Hawks’s Barbary Coast (1935) and Two Years Before the Mast (1946), with my first appreciation of the soon-to-be-blacklisted Howard Da Silva playing a brutal sea captain overshadowing its bland star Alan Ladd, and The Great McGinty (1940), to say nothing of his commanding performance as Sergeant Markoff in William Wellman’s Beau Geste (1939) that I first saw on a double bill at the National Film Theatre in 1974, alongside Ronald Colman’s silent 1926 version. Donlevy (1901-1972) was definitely an accomplished actor who often made distinctive impressions in his various screen roles during the height of his career. Today, outside classical Hollywood film circles, he is usually the subject of detrimental references on Facebook Quatermass sites with posters often siding with writer Nigel Kneale as to his unsuitability for the role, an attitude both unfair to the actor and unwilling to consider other important aspects of the production period.

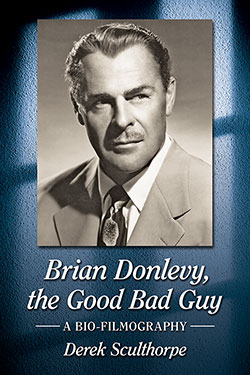

As with his previous books, with Brian Donlevy, the Good Bad Guy (McFarland, 2017) Leeds-based Yorkshire independent scholar and archivist Derek Sculthorpe has done a great job in providing readers with a modest, but very useful bio-filmography of this actor and his achievements in film, radio, theater, and television, which provides welcome avenues for looking up whatever is available and engaging in further debate on the significance of this actor’s career. Many independents outside the academy not only display more historical knowledge than certain self-proclaimed experts within the ivory tower but also engage in pioneering work of their own, such as Anthony Slide, Gary P. Rhodes, and Dan Van Neste, whose excavations on The Whistler film series and Ricardo Cortez shed light on important areas often neglected by contemporary establishment scholars. This book on Brian Donlevy falls into this category. Thirteen chapters with preface, epilogue, bibliography, index, and appendices, including surviving recordings of the actor, fill this 210 page study.

Sculthorpe’s preface notes that although the actor was often associated with playing bad guys, he was capable of more diverse performances akin to his actual real-life gentle nature.

Sadly, his vulnerability was seldom revealed on screen and he was too often used – and allowed himself to be used – as shorthand for a tough villain who gets his comeuppance. When he was given the chance to play against type or let his guard down, he was a different and far more interesting actor. (1-2)

This was certainly the case in Donlevy’s multifaceted performance in Preston Sturges’s The Great McGinty (1940) that he repeated with his co-star Akim Tamiroff in a brief reprise in the same director’s The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944), as well as his sympathetic, naïve political fixer Paul Madvig in the second film version of The Glass Key (1941) that is far better than Edward Arnold’s previous performance in the 1935 version starring George Raft. He also delivered a sympathetic supporting performance in the otherwise uneven The Great Man’s Lady (1942), which overshadowed its official stars Barbara Stanwyck and Joel McCrea.

As usual, Sculthorpe documents the actor’s early life, stage appearances, and Hollywood roles in his usual meticulous manner. While justifiably acclaiming Donlevy’s Best Supporting Actor-nominated role in Beau Geste, he also mentions other neglected and worthy roles, such as portraying the title figure in The Remarkable Andrew (1942) playing the ghost of Donald Trump’s favorite President Andrew Jackson, and the fact that the actor could have appeared in British films well before his Quatermass debut. He was first choice for the role eventually played by Michael Redgrave in Thunder Rock (1944), directed by John Boulting and based on Robert Ardrey’s anti-isolationist play. “Donlevy was an interesting choice, as an American actor in the lead would have given this movie greater resonance in the US at the time” (70). MGM originally conceived the project before America entered the war, at a time of great isolationist sentiment. The actor was also sought for a later abandoned film project involving the transportation of planes to England (71). But the most remarkable lost opportunity was Michael Balcon’s desire to cast Donlevy in San Demetrio London (1943) that collapsed due to the actor’s pressing Hollywood studio commitments (76). As with his book on Claire Trevor from McFarland, Sculthorpe often lists the roles the actor could have played, had no other factors intervened. With Donlevy, his findings suggest that the actor could have cinematically saved Britain on more than one occasion, if not confined to the realm of science fiction, especially at a time when his stardom was its most strongest – wartime. He would later perform another accomplished role as a Bomber Command figure in the post-war Command Decision (1949), directed by Sam Wood, where Donlevy played opposite Clark Gable, very much like his acclaimed performance in Wake Island (1942).

However, some errors occur that need correcting. It was Howard Hughes, rather than Hawks, who was responsible for The Outlaw (1943), although the latter may have shot some scenes before his removal from the project (see 64). Should not the undated “The Best Years of Our Life” refer to Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives? (86).

The post-war era resulted in many changes that affected Hollywood stardom in several instances, with actors gradually slipping from the pinnacle of success – often through no fault of their own – due to new industrial conditions and changing audience tastes. Despite these factors and personal issues all leading to the actor’s increasing alcoholism in the 1950s, Donlevy did deliver some outstanding performances in the undervalued Impact (1949) that Sculthopre compares to George Orwell’s Coming Up for Air (1939) as well as making a successful transition to the more challenging medium of television, for which he received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (131). Significantly, he was scheduled to play the father in Jean Renoir’s The River (1951), but the role went to Esmond Knight (121). Also, as well as being involved in production projects, all unfortunately unsuccessful, one of which would have starred Anna Magnani in Nova Scotia locations in 1949, he successfully pitched the idea of Dangerous Assignment as a radio series that ran from 1949-1953, alongside its NBC TV version in 1952. He also repeated his role as The Great McGinty alongside Thomas Gomez in the Tamiroff role in a 1955 TV production (135) and performed well in a poignant supporting role in Joseph H. Lewis’s The Big Combo in the same year.

For members of the various Quatermass Facebook sites, chapter 11, “Quatermass to the Rescue,” will be of special interest. Writer Nigel Kneale always resented Donlevy’s casting in the first two film versions of his teleplays directed by Rudolf Cartier, as Kneale regarded the actor as an alcoholic fading American star hired to get American distribution, a common practice at the time. However, while admitting that Donlevy did have a fondness for drink at this stage of his career, Sculthorpe defends the actor from often unjustified accusations. He also quotes director Val Guest, Quatermass II co-actors Bryan Forbes and William Franklyn, to the effect that Donlevy’s performances were always professional in front of the camera. Despite Kneale’s preference for a British actor in the mold of the late Reginald Tate in the first 1953 Quatermass series, Sculthorpe delivers a convincing defense of Donlevy’s often maligned performance. He also speaks positively about one of Donlevy’s later roles in another British made film, Curse of the Fly (1965), that he feels has been unjustly neglected (153-155), where the actor exhibits the difficult task of displaying “conflicting emotions” (155). However, Sculthorpe’s defense of Donlevy’s Quatermass is worth considering.

Donlevy’s portrayal of the professor is hardly likely to be universally admired any time soon, but was arguably more in tune with the thrusting spirit of the atomic age than the erudite gent that Kneale first imagined. Once a written creation is manifested on screen, he is out of his creator’s hands and takes on a life of his own. The test of the strength or weakness of any invented character is if he or she can be reinterpreted time and again and retain his or her essential self. On any scale, Quatermass passes that test. (144)

One could also say the same about the many reincarnations of Dr. Who, but there will always be debate on that issue.

The epilogue comments that Donlevy was a “paradox” (163) but delivers a fitting conclusion concerning the actor’s importance today:

The received wisdom is that Donlevy’s career was largely a failure. But if failure includes an Academy award nomination for Beau Geste, admiration from the New York critics and the Soviet government for Wake Island, an acclamation for many of his film, a successful theater, television and radio career, and a hit tv series, then perhaps failure is not so bad after all. Few actors before or since quite had his ability to make villains likeable. He had a sure gift for satire and a surprising range. (164)

Tony Williams is Professor and Area Head of Film Studies in the Department of English, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale and a Contributing Editor to Film International.

Read also:

Journeywoman – Claire Trevor: The Life and Films of the Queen of Noir by Derek Sculthorpe