By Tony Williams.

If Robin Wood once said on a DVD feature, “If you don’t like Marnie, then you don’t like Cinema”, any encounter with Hawks’s Only Angels Have Wings (1939) challenges any viewer in a similar manner. As Gerald Mast (105) wrote, the film serves as “a cutting edge in separating those who can and cannot enter the Hawks world with their minds and feelings”. In his indispensable monograph on Hawks Robin Wood notices key parallels with the work of Joseph Conrad in terms of the assertion of human values against a bleak world and no matter how juvenile this assertion may appear to be, it involves for Wood “the assertion of basic human qualities of courage and endurance, the stoical insistence on innate human dignity” (17) in the face of hostile forces ready to extinguish the last flickering light of humanity that following any crash evokes the sound of silence with the arbitrary death of yet another victim of an arbitrary universe. All Hawks heroes and heroines face the realization that existence and personal relationships may be merely just “for a day”. But that fragile transitory day represents a heroic assertion of life in the face of the darkness that will one day overwhelm us all whether in the distant future or some arbitrary final unforeseen action of Flitcraft’s beam manifesting itself from Dashiel Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon (1939). Although many balk at the supposed juvenile nature of Only Angels, it is still a modern work recognizing tragedy as the everyday companion of human existence rather than false romantic ideals of optimism and guaranteed survival. In this sense, as Henri Langlois once recognized, Hawks and his films express an essential modernity, one that is never totally nihilistic or pessimistic but stressing the optimistic elements of collaboration and friendship no matter how transitory they may be. In this way, Langlois is correct in recognizing the film’s modernist associations, one that blends the classical (Conrad, Hemingway, Shakespeare as in the relevant quotation from Henry IV, Part One that Mast refers to) with the popular (the cinematic aviation genre) in a manner that facile supporters of postmodernism can never understand. Blurring of boundaries occurred well before the emergence of Lyotard’s now redundant thesis in an era that has seen the return of those grand narratives he and his supporters once brusquely dismissed.

Only Angels Have Wings still reigns supreme as one of classical Hollywood’s cinematic modernity narratives in its blending of the popular action-adventure genre with classical tragedy. Death and separation may affect any of the central characters as it did several decades later to aviation pilot Paul Mantz who died during the filming of Robert Aldrich’s The Flight of the Phoenix (1966) thus accounting for the conclusion in which the happy landing of the plane never appeared. Only Angels Have Wings may have had its forerunners such as John Ford’s Air Mail (1932) and Lew Landers’s Flight from Glory (1937) that occur during the middle and the end of the aviation cycle but neither exhibits that creative transformation endemic to Hawks’s best work nor, unlike Air Mail, the offer of that important second chance for a fallen angel to redeem himself.

As Wood wrote decades ago, Hawks’s films have that rare quality in twentieth century art (one even rarer in the age of Roth and Tarantino), “convincingly to portray creative relationships in which the characters help each other, and through which they develop towards a greater maturity, self-reliance and balance.” How much have we lost since then!

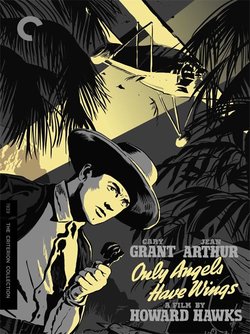

This Criterion DVD/Blu-Ray version of the film is a welcome addition to its catalog. Although I admit my untrained eye is not equal to the professionalism of DVD Beaver, I enjoyed seeing a copy in which the deliberate surrounding darkness is dominant rather than being diminished as in most unhappy DVD reproductions of film noir accompanied by contrast elevated to the highest level to make the work equivalent to the high-tech digital reproduction that Hawks and his collaborators never had in mind (this would make it equivalent to the disparaging term of “decadence” used by Jean Renoir in his famous interview with Jacques Rivette whenever total technical realism is the goal). It is far from coincidental that Michael Sragow in his accompanying essay refers to Jacques Rivette’s 1953 Cahiers du Cinema review where the critic and future director acclaims the director’s “marvelous blend of action and morality” and “pragmatic intelligence” in the final part of an aviation trilogy begun with The Dawn Patrol (1930) and continued with Ceiling Zero (1936) where all the preceding ingredients combine into final perfect realization. The fragility of light in the night scenes where those kerosene lamps noted by Mast “define Dutchy’s bar as `a clean well-lighted place’ (to use the title of a famous Hemingway story), a bright social and emotional refuge from the darkness and loneliness outdoors” (107), reveal the intuitive recognition of the Criterion team as to how this film should be seen. Indeed, the predominant darkness surrounding the final moments of Kid visually reveal him as an expiring flicker of life in this poignant scene, thanks to the restoration by experts who know how a certain scene should look.

This Criterion DVD/Blu-Ray version of the film is a welcome addition to its catalog. Although I admit my untrained eye is not equal to the professionalism of DVD Beaver, I enjoyed seeing a copy in which the deliberate surrounding darkness is dominant rather than being diminished as in most unhappy DVD reproductions of film noir accompanied by contrast elevated to the highest level to make the work equivalent to the high-tech digital reproduction that Hawks and his collaborators never had in mind (this would make it equivalent to the disparaging term of “decadence” used by Jean Renoir in his famous interview with Jacques Rivette whenever total technical realism is the goal). It is far from coincidental that Michael Sragow in his accompanying essay refers to Jacques Rivette’s 1953 Cahiers du Cinema review where the critic and future director acclaims the director’s “marvelous blend of action and morality” and “pragmatic intelligence” in the final part of an aviation trilogy begun with The Dawn Patrol (1930) and continued with Ceiling Zero (1936) where all the preceding ingredients combine into final perfect realization. The fragility of light in the night scenes where those kerosene lamps noted by Mast “define Dutchy’s bar as `a clean well-lighted place’ (to use the title of a famous Hemingway story), a bright social and emotional refuge from the darkness and loneliness outdoors” (107), reveal the intuitive recognition of the Criterion team as to how this film should be seen. Indeed, the predominant darkness surrounding the final moments of Kid visually reveal him as an expiring flicker of life in this poignant scene, thanks to the restoration by experts who know how a certain scene should look.

Much has been written and debated about this film, the latter represented by a famous 1977 Film Comment article by Raymond Durgnat titled “Hawks isn’t good enough” prompting William Paul’s reply (in the same magazine, 1978) arguing that this particular negative response wasn’t “good enough”. But rather than contribute to the debate, this review, like its predecessor on In A Lonely Place, will emphasize the collective features of this DVD that make it “good enough” in terms of the Criterion approach. In addition to the new 4K digital restoration, this special edition contains added features such as audio extracts from Peter Bogdanovich’s 1972 conversation with Hawks in which both participants appear at the peak of their vocal powers articulating information that has been published elsewhere, Sragow’s above-mentioned essay appropriately titled “Hawks’s Genius Takes Flight”, a new interview with David Thomson, and a short documentary “Howard Hawks and his Aviation Movies.” Like other Criterion DVD releases, this one also features the 1939 Lux Radio Theatre adaptation hosted by a blustering and pompous Cecil B. DeMille eager to draft Hawks into his bombastic patriotic club. DeMille is eager to point out the proximity of the broadcast to Memorial Day and ends by attempting to include the film into a familiar mode of American traditional values that have little to do with it.

However, C.B. aside, this 60-minute adaptation has the value of reuniting most of the original cast with Grant, Arthur, Mitchell, Hayworth, and Barthelmess performing their screen performances with Alan Ladd substituting for Allyn Joslyn’s Les. Gent Sheldon is mentioned but remains subordinate, the scene where he shows he is “no good” and expelled from the professional group omitted from this version. The defiant “Some of these Days” number is absent but “Peanut Vendor” remains sung by a much more vocal Cary Grant here. During the intermission a real life aviator flying the much safer Yankee Clipper service with both mail and passenger service is interviewed. As a result of the presence of a studio audience who get the jokes, laughter occurs after Kid’s line, “Yes, they have no bananas” and Geoff’s realization that his friend’s double-headed coin successfully aided his liquid refreshment. “No wonder I’ve been buying you drinks all year.” The fight where Les breaks his arm is edited out as is the second scene of Geoff with Judy when he makes her sober up. The line, “Judy, you’re no good. You never were” now appears in their first solitary encounter. Despite the problematic nature of abbreviations for radio, the inclusion of these versions on DVDs aid in underscoring differences between acoustic and visual representations, as in the opening scene where Bonnie feels herself threatened by Joe and Les and refers to the butcher’s knife she wields in her defense until she realizes she is in the welcome presence of gringos who do not speak Barranca’s “pig-Latin.” Such were attitudes then and we are not securely far away from them as the speeches of a certain Republican Presidential candidate reveal at this time.

Though lacking an audio-commentary which, after all, is not that necessary in view of the two excellent books by Mast and Wood that I use for my Hawks classes, this is another “good” addition to the Criterion Collection, in the fullest Hawks sense of the word.

References

Durgnat, Raymond (1977) “Hawks Isn’t Good Enough”. Film Comment 13.4, 8-23.

Langlois, Henri (1963) “The Modernity of Howard Hawks.” Translated by Russell Campbell. Focus on Howard Hawks. Ed. Joseph McBride. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, Inc., 65-79

Mast, Gerald (1982). Howard Hawks – Storyteller. New York: Oxford University Press.

Paul, William (1978) “Hawks vs. Durgnat.” Film Comment 14.1: 68-71.

Wood, Robin (2006) Howard Hawks. New Edition. Detroit: Wayne State University Press

Tony Williams is Professor and Area Head of Film Studies in the Department of English, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale and a Contributing Editor to Film International. His James Jones: the Limits of Eternity is scheduled for publication by Rowman and Littlefield, Inc. in August 2016.