By Jeremy Carr.

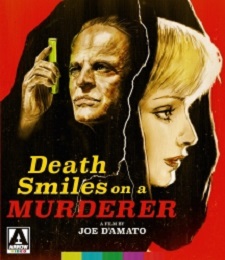

Highlighting the Arrow Video Blu-ray of Death Smiles on a Murderer (also known as Death Smiled at Murder) is a video essay by Kat Ellinger. In this roughly twenty-minute supplement, “Taboo: Sex, Death and Transgression,” Ellinger considers, as much as time permits, the nearly 200 films directed by Aristide Massaccesi (most popularly credited as Joe D’Amato, he assumed some 50-plus pseudonyms). In an era engorged with frequently outrageous horror and exploitation fare, Massaccesi is, Ellinger notes, among the more “daring and transgressive.” No small feat, to be sure. What she then reviews is a remarkably comprehensive sampler of what was produced by this often audacious filmmaker. Or, perhaps appetizer is a better word, as those less familiar with Massaccesi, and those with a taste for his brand of cinematic cuisine, will likely find intrigued inspiration in this menu of titles and, in many cases, their accompanying moments of salacious subject matter. In that, in putting into context Massaccesi’s inexplicable range of material, and in appreciating his work for just what it is – purposefully and unapologetically shocking entertainment – Ellinger’s essay is a valuable primer for Death Smiles on a Murderer. Massaccesi, she says, reveled “in the grotesque, the erotic, and the downright absurd.” And, she adds, “this was only the beginning.”

Released in July 1973, Death Smiles on a Murderer is the only film Massaccesi released under his own name, which is a testament to the quality, or at least the distinction, of this paranormal/romantic murder mystery. “The movie was special,” Massaccesi states in “D’Amato Smiles on Death,” a short archival interview also included on the Arrow disc, although this catch-all of cross-genre tropes is, he readily admits, “over-the-top.” Set in Austria during the early part of the twentieth century, the film’s primary character is Greta von Holstein, played by Ewa Aulin, who through the late sixties and into the early seventies graced several modish thrillers similar to Death Smiles on a Murderer (Giulio Questi’s 1968 feature Death Laid an Egg, in which Aulin appears alongside Gina Lollobrigida and Jean-Louis Trintignant, is a good example). While a beloved actress, as Tim Lucas notes in his commentary track, Aulin was also, and quite unashamedly, “objectified” in most of her roles (even Lucas makes sure to note her measurements). In “All About Ewa,” a forty-three-minute interview with the star, she discusses Massaccesi (“a great artist, a visionary”) and happily touts what she sees as the “good message” of Death Smiles on a Murderer: “You can be killed, even if you’re already dead.”

And true enough, that proposal is at the center of what transpires in the film, as it begins with Greta’s corpse, mourned by her hunchback brother, Franz (Luciano Rossi). In a quickly introduced flashback, Franz is shown to have had rather illicit feelings for his sister. He calls her gentle and defenseless, just before she aggressively slaps him, her clothes fall off, and Massaccesi cuts to the two of them in bed, presumably having made up and then some. It’s a sort of playful perversity that lingers throughout Death Smiles on a Murderer, enticing a number of other characters in the past and present (and which is which, isn’t always so obvious). For starters, though, there is the rich Dr. von Ravensbrück (Giacomo Rossi Stuart), who impregnates Greta but leaves her to die during childbirth. That, in turn, sets Franz to vengefully implement an Incan formula that will bring Greta back from the dead. Newly reanimated, she sets her sights on reckoning with the Ravensbrück family, including unsuspecting son Walter, played by Sergio Doria, and his wife Eva, played by Angela Bo, both of whom soon fall for this enigmatic beauty (unlike Rossi and Doria, who had extensive experience in Italian cinema of the period, this would be the seventh and final film of Bo’s career). From the ardor emerges animus and scheming and, much too briefly, the appearance of Dr. Sturges, played by the always curious Klaus Kinski. In this his follow-up to Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), Kinski’s debonair mad scientist discovers the formula and embarks on his own experimentation, taking place in an exotic laboratory and an equally decrepit cavernous operating room. Kinski doesn’t say much – his infamously erratic behavior was and is part of the appeal in his casting – but his expressive glances convey a prevailing sense of being in far deeper thought than he need be. Ultimately, however, his is but a side plot discarded in favor of the more immediate concerns of Greta’s backstory, marred by abuse, and her current retribution, which incorporates sexual desire, jealousy, and violence, and sometimes all three at once, as in her bathtub confrontation of Eva.

And true enough, that proposal is at the center of what transpires in the film, as it begins with Greta’s corpse, mourned by her hunchback brother, Franz (Luciano Rossi). In a quickly introduced flashback, Franz is shown to have had rather illicit feelings for his sister. He calls her gentle and defenseless, just before she aggressively slaps him, her clothes fall off, and Massaccesi cuts to the two of them in bed, presumably having made up and then some. It’s a sort of playful perversity that lingers throughout Death Smiles on a Murderer, enticing a number of other characters in the past and present (and which is which, isn’t always so obvious). For starters, though, there is the rich Dr. von Ravensbrück (Giacomo Rossi Stuart), who impregnates Greta but leaves her to die during childbirth. That, in turn, sets Franz to vengefully implement an Incan formula that will bring Greta back from the dead. Newly reanimated, she sets her sights on reckoning with the Ravensbrück family, including unsuspecting son Walter, played by Sergio Doria, and his wife Eva, played by Angela Bo, both of whom soon fall for this enigmatic beauty (unlike Rossi and Doria, who had extensive experience in Italian cinema of the period, this would be the seventh and final film of Bo’s career). From the ardor emerges animus and scheming and, much too briefly, the appearance of Dr. Sturges, played by the always curious Klaus Kinski. In this his follow-up to Werner Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), Kinski’s debonair mad scientist discovers the formula and embarks on his own experimentation, taking place in an exotic laboratory and an equally decrepit cavernous operating room. Kinski doesn’t say much – his infamously erratic behavior was and is part of the appeal in his casting – but his expressive glances convey a prevailing sense of being in far deeper thought than he need be. Ultimately, however, his is but a side plot discarded in favor of the more immediate concerns of Greta’s backstory, marred by abuse, and her current retribution, which incorporates sexual desire, jealousy, and violence, and sometimes all three at once, as in her bathtub confrontation of Eva.

In essence, this set-up is straightforward, but Massaccesi’s presentation is such that much else is left equivocally incomplete and stylized. The resulting ambiguity muddles certain plot points, enhancing what is a suitably deceptive and unexplained series of events, indeterminate and fluid and underscored by metaphysical proposals that make anything possible and, in this schematic, reasonably plausible, all without the necessity of explanation. A rampant voyeuristic fascination is repeated in point of view shots that don’t always belong to the same person, adding to the concealment of just who is doing what; Massaccesi keeps Death Smiles on a Murderer in a state of constant subjective-objective flux, challenging the reliability and validity of what is seen. Some hallucinatory visions are consigned to a given character’s vantage, while others occur in a detached realization; some visions are shown by Massaccesi, others are merely implied by the look on a character’s face. The gothic setting, an isolated country estate, is intimidating if not exactly scary, though its stuffy, affluent rigor does serve as a fittingly sparse, dilapidated yet elegant backdrop for the coarse drama that unfolds. Slight historical details generally recede against the intensely lurid colors used by Massaccesi to illustrate the picture. As a seasoned director of photography, and in that regard being somewhat overqualified as Lucas argues, Massaccesi’s visual talents take shape in exaggerated lights and shadows, variable camera placement, haunting slow motion, distorted wide angle lenses, and a dreamy, languid, and compelling erotic ambience (the film looks excellent in this 2K restoration from Arrow).

Bearing in mind the film’s horror/giallo likeness, Death Smiles on a Murderer has its fair share of grisly content: a needle through Greta’s eyeball, for example, or an impaled coachman with his innards spewing forth (the working title of Death Smiles on a Murderer was “Seven Strange Corpses”). And with references to such literacy antecedents as Edgar Allan Poe and H.P. Lovecraft, Massaccesi also includes a scene of murder by masonry and a silly, predictable masquerade twist. On the other hand, extended passages of no dialogue (just as well given how stale the writing is) are carried along by Berto Pisano’s whimsical score; indeed, as Lucas observes, the film relies on the music to sustain scenes of relative inaction and to “invest the visuals” with continuity and atmosphere. In assessing the flexible timeline of Death Smiles on a Murderer, noting its chronology that contentedly goes from facts to impressions and, eventually, to the realm of uncertain symbolism, Lucas recognizes Massaccesi’s skill and excuses some of the film’s more perplexing elements as poetry over narrative. Lucas even seems to lament the film in light of the director’s later work. Though one moment from Death Smiles on a Murderer – a minute-long death by tossed cat – is deemed by Lucas “beyond terror, beyond taste,” those words are nothing compared to his comments concerning the “gutter trash” later assigned to Joe D’Amato, dubious titles like the Video Nasty Anthropophagus (1980) and the director’s foray into pornography.

Bearing in mind the film’s horror/giallo likeness, Death Smiles on a Murderer has its fair share of grisly content: a needle through Greta’s eyeball, for example, or an impaled coachman with his innards spewing forth (the working title of Death Smiles on a Murderer was “Seven Strange Corpses”). And with references to such literacy antecedents as Edgar Allan Poe and H.P. Lovecraft, Massaccesi also includes a scene of murder by masonry and a silly, predictable masquerade twist. On the other hand, extended passages of no dialogue (just as well given how stale the writing is) are carried along by Berto Pisano’s whimsical score; indeed, as Lucas observes, the film relies on the music to sustain scenes of relative inaction and to “invest the visuals” with continuity and atmosphere. In assessing the flexible timeline of Death Smiles on a Murderer, noting its chronology that contentedly goes from facts to impressions and, eventually, to the realm of uncertain symbolism, Lucas recognizes Massaccesi’s skill and excuses some of the film’s more perplexing elements as poetry over narrative. Lucas even seems to lament the film in light of the director’s later work. Though one moment from Death Smiles on a Murderer – a minute-long death by tossed cat – is deemed by Lucas “beyond terror, beyond taste,” those words are nothing compared to his comments concerning the “gutter trash” later assigned to Joe D’Amato, dubious titles like the Video Nasty Anthropophagus (1980) and the director’s foray into pornography.

The Arrow Video disc of Death Smiles on a Murderer also includes two essays, one by Stephen Thrower and one by Roberto Curti, and an interview with co-writer Romano Scandariato. All three provide additional details about the making of Massaccesi’s film, details that are, not surprisingly, full of contradictions. For one thing, according to Thrower, who cites co-writer and production designer Claudio Bernabei (the script is credited to Massaccesi, Scandariato, and Bernabei, though the extent of their involvement is debatable, as is the nature of Massaccesi’s initial story, which Scandariato said was “more or less one page”), it took around seven or eight days to shoot Death Smiles on a Murderer. That, Thrower writes, is “phenomenally quick for such a handsome picture.” Which is true – what Massaccesi had working against him makes this film exceptional in many ways. Furthermore, as Curti notes, narrative components were added throughout the shooting process and on-set improvisations constantly changed the production (he also argues for a shooting schedule that was “two or three weeks at the most”). In any event, although Death Smiles on a Murderer has a sleazy texture to suit its sleazy characters, and its crude, inflated anguish gives way to equally overblown vengeance and guilt, Massaccesi clinches what matters most. And to that end, Thrower rightly gives credit where credit is due: “The film’s oddball delirium is a finer reward than a banal dish of common sense.”

Jeremy Carr teaches film studies at Arizona State University and writes for the publications Film International, Cineaste, Senses of Cinema, MUBI/Notebook, Cinema Retro, Vague Visages, Cut Print Film, The Moving Image, Diabolique Magazine, and Fandor.

Read also: