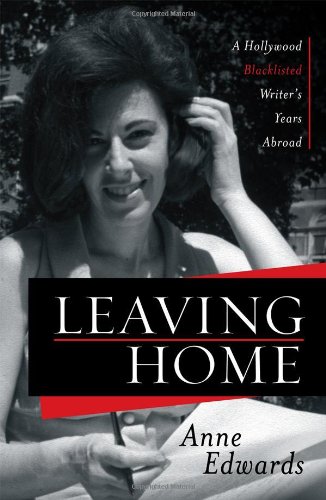

Perhaps best known as a biographer of the rich and famous from across the spectrum, Anne Edwards has told the life stories of everyone from screen figures Shirley Temple, Judy Garland, Vivien Leigh and Ronald Reagan (her book Early Reagan was a Pulitzer Prize nominee) to the dynastic sagas of the DeMilles, the Grimaldis of Monaco, the Aga Khans and the royal family of Great Britain. She also has written popular children’s books, best-selling novels, scripts for television and film, and now an important memoir.

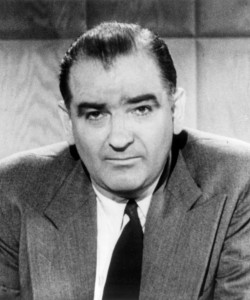

Born in California and raised in the shadow of the film industry (“Uncle Dave” ran Chasen’s, a restaurant for the Hollywood elite), she was a young divorcee with two small children when blacklisted by the House Committee on Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) for her political beliefs and activities. Among her sins was being related by her first marriage to writer and director Robert Rossen, one of the original “Hollywood 19,” who eventually became a cooperative HUAC witness.

Script work overseas led Edwards to two decades of living in England, France, and Switzerland. She tells her story in Leaving Home: A Hollywood Blacklisted Writer’s Years Abroad (2012) a powerful memoir that weaves the history of the blacklist and her own intimate and professional experiences into a moving testament of integrity and survival. The honest pleasures of this book include many capsule portraits of prominent as well as overlooked blacklist victims. Among these are Rossen, who made the Oscar-winning All the King’s Men before the blacklist and such pictures as The Hustler after his “friendly” HUAC testimony, and who is treated by the author with dignity and complexity. The great screenwriter Sidney Buchman (Mr. Smith Goes to Washington) comes across as a wise and sophisticated soul, with a personal backstory that is unforgettable and poignant. Many less familiar names receive fascinating close-ups. Edwards agreed to answer a series of questions by email from Los Angeles, where she lives today.

Patrick McGilligan: I can’t help but notice that in the book you are somewhat vague about your politics before the blacklist. Were you a Communist, and if you were, why don’t you talk about it? If you weren’t, why were you a target of HUAC?

Anne Edwards: I say clearly in the book that I was never a member of the Communist Party. Of course, hundreds of others were not and were still a target of HUAC. In my case, I can only assume what appears to be the most obvious: I was closely associated with several well-known writers/directors/actors who were prime targets – names that were well enough known, as were their credits (movies) – to be desirable additions for HUAC to persecute and so gain headlines (or at least major media coverage). I lived with the Rossens (Robert and Sue, my in-laws) for a lengthy time during the difficult early period of HUAC when Bob was denying any association with the Communist Party. I had close association as well with John Garfield and numerous other famous members of the Hollywood community who HUAC was anxious to have named (even if they had been named before).

Also my credits, however few, dealt with stories putting forth strong, liberal story lines. Mainly, I suppose, my original screenplay, “Riot Down Main Street,” sold to 20th Century Fox, based on the true story of a Texas town that had refused to bury the remains of a returning fallen hero of the Korean War who, though an American citizen, was of Latino parentage […] and the town’s cemeteries were for “whites only.” The mortuary wanted the casket to be moved forty miles to be buried over the Mexican border. (He was finally buried in Arlington.)

The studios all had HUAC “workers” cooperating from inside. The development of my screenplay was immediately cancelled.

I had also sold an original screenplay, “Quantez,” to Universal, a Western about a standoff between an Indian band and a group of “teacherly” whites who had occupied a ghost town on their sorry travel westward. The Indian’s side was dealt with some sympathy. In 1957, it was eventually adapted by Robert Campbell with the attitude decidedly reversed to become a shoot-out film although a lot my scenes did remain along with the original title of my screenplay.

I had contributed what little I could spare to several causes that seemed in some mad way to raise red flags. They would seem very common to charity foundations today – and did to me at the time.

HUAC often speared people like myself (not well-known but well-connected) for the direct purpose of badgering them into naming names that would be well-known to the general public. The phrase “guilty by association,” was like a deadly virus at that time poisoning the Hollywood community.

I thought I would ask you a little about actor John Garfield, who is one of the most famous names affected by the blacklist. You talk in your book about how the blacklist actually “killed” some people, and I know this is true but I don’t think people today understand this at all. Garfield seems someone not unlike yourself in his politics – engaged, committed, active – never a Communist, yet tortured to death by HUAC. You say in the book that you knew him well at a certain point. What more can you tell us?

Jule [John] Garfield and his wife Robbie were somewhat like family members. They were both supportive of me from the time of my engagement and marriage to my first husband, and after Jule’s tragic early death at thirty-nine Robbie remained a good friend. The Rossens and the Garfields had been close since their pre-Hollywood New York years. Jule and Bob had started their careers with the Group Theatre, came to Hollywood at the same time and were both signed by Warner Bros. Bob wrote several screenplays that starred Jule. When the Rossens were abroad (late 40’s, early 50’s), my husband and I moved in with the children (three: the oldest, Carol, 11; I was 22). Robbie was somewhat my surrogate mother to go to, Jule my creative adviser.

Jule [John] Garfield and his wife Robbie were somewhat like family members. They were both supportive of me from the time of my engagement and marriage to my first husband, and after Jule’s tragic early death at thirty-nine Robbie remained a good friend. The Rossens and the Garfields had been close since their pre-Hollywood New York years. Jule and Bob had started their careers with the Group Theatre, came to Hollywood at the same time and were both signed by Warner Bros. Bob wrote several screenplays that starred Jule. When the Rossens were abroad (late 40’s, early 50’s), my husband and I moved in with the children (three: the oldest, Carol, 11; I was 22). Robbie was somewhat my surrogate mother to go to, Jule my creative adviser.

I was already on the start of my writing career (screenplays, at that time). Jule was interested, helpful, concerned. He liked to tell me stories about his own life, his memories of growing up poor in a New York ghetto, the troubles he got into as a kid, his hitching rides on freight trains and being tossed out without a cent, and having to struggle to get a meal (this was at the height of the Depression). His criticism was always constructive. He wanted me to understand the characters I engaged in my writing, to have in my head a solid backstory. And he was great when it came to sharpening dialogue. I don’t know why he didn’t write – maybe if he lived longer he would have done so.

What was he like? As you can see from the above – generous with his time – as was Robbie (they had two very young children: Julie and David ). Jule had a charismatic personality. I can still hear his voice and speech pattern in my head. He looked you straight in the eye when he spoke to you. He could get passionate over the simplest things. He also could be cynical. He was, as you probably have observed, short and feisty (as was Bob R.) and had boxed as a kid (as had Bob R.). I think he fought for a cause – certainly leaned left – but was never a joiner. He died (1952) before Bob went before the Committee and gave names. Instinctively I feel that would have ended their friendship.

In his last few years Jule formed his own company – in part, I am sure, because it was the only way he could work. It was tough going for him in those last two years. As I knew him, I never could see him as a womanizer. He and Robbie seemed a very together couple – he was a loving father – proud of his small children. I think everyone who really knew them was shocked at the manner of his death (by a heart attack in bed with a young woman). But he was under extreme pressure from HUAC, his work, his future etc. I considered him a victim of HUAC and those terrible times when no one knew who was a real friend – and when your career would become past tense.

I retained my friendship with Robbie. Her second husband was Leon’s attorney and business manager. In the early Sixties, David Garfield came to London to attend RADA and moved in with Leon and myself for a time. He, tragically, also died young – even younger than his father.

I enjoy the fact that you are so warm in the book in your feelings towards Lester Cole, one of the Hollywood Ten. Often he is maligned in other accounts as a ‘B’ screenwriter or political hard-liner. (I knew him and always liked and admired him.) Since he is the member of the Hollywood Ten that you appear to have known best, can you tell us a little about his talent and personality and the circumstances of your friendship?

Well, I met Lester in Hollywood (can’t remember how). Then, in London, we both worked on a project for fellow expat, writer-producer Carl Foreman. Lester was at times a very angry man. Neither of us received a fair wage from Carl – who had managed to procure a secret session with HUAC, clearing the way for him to make films under his own name and release them in the States. It ate at Lester – along with his year in prison (he still had nightmares about it) for refusing to name names. His wife divorced him, and none of his so-called old friends came to his aid (or so he said – bitterly). He was bruised deeply, and despite his ferment I liked and believed I understood him. His problems went back before HUAC really, but were bolstered by it. He had felt he had never got the good assignments in Hollywood and had not been able to make the name for himself that he thought he deserved, and now he was deep into mid-life and could not see how he was going to “rise up from the ashes” when he could not use his name.

Well, I met Lester in Hollywood (can’t remember how). Then, in London, we both worked on a project for fellow expat, writer-producer Carl Foreman. Lester was at times a very angry man. Neither of us received a fair wage from Carl – who had managed to procure a secret session with HUAC, clearing the way for him to make films under his own name and release them in the States. It ate at Lester – along with his year in prison (he still had nightmares about it) for refusing to name names. His wife divorced him, and none of his so-called old friends came to his aid (or so he said – bitterly). He was bruised deeply, and despite his ferment I liked and believed I understood him. His problems went back before HUAC really, but were bolstered by it. He had felt he had never got the good assignments in Hollywood and had not been able to make the name for himself that he thought he deserved, and now he was deep into mid-life and could not see how he was going to “rise up from the ashes” when he could not use his name.

He mellowed considerably once he married his second wife – Kay, a very nice, sophisticated, comfortably well-off lady about his own age. I believe she was from San Francisco; at least, once he returned with her to the States that is where they settled. He had short stays with me in both the South of France and Stockbridge (when Steve Citron, my third husband and I had the inn)[1] – while Kay was off visiting family or some such.

When I asked Clancy Sigal to tell me about some of the blacklisted London community, he mentioned the names of several people I had never heard of – people like comedy writer Reuben Ship, that’s one I recall. You say in your book there were hundreds of blacklistees there in the 1950s and 1960s. I assume many of them were not well known publicly or in terms of their credits. Can you pick one out that you didn’t profile in your book, and tell us a little about him/her and of people’s struggles to create a new life for themselves?

Yes, there were well over a hundred HUAC victims in London (and their families). It was the country to go to. I knew a fairly large number and heard word of many others. I mainly remained close to the writers, directors, etc., whose names were familiar to the press. But there were fine cameramen – sound men (no women in these categories that I know of) – editors etc. It was a little easier, however, for blacklisted technical personnel to find work on foreign films as their knowledge of modern film technique was badly needed and credit was not as important in those technical jobs.

The actress, Betsy Blair, was in London – she had been nominated for an Academy Award for her lead role in Marty. Her marriage with Gene Kelly was a shambles because of her left-leaning beliefs (he was at the height of his career and did not want to see it crumble, and of course he was not, at heart, as political as Betsy was). It was most difficult for actors to find work in their field, as obviously they could not hide their familiar face behind a new name. Betsy was remarried to the director Karl Reisz (a Czech who came to England during the war and had made a tremendous name for himself in the mid-fifties to the sixties as the director of what was then called “The British Free Cinema”). Betsy wrote a very good memoir about her own situation [The Memory of All That (2003)]. She died only a few years ago but never returned to the States.

There was Ben Barzman and his wife Norma (who also lived in London and the South of France when I did) but we never became friends (no special reason that I can recall). And Bernhard Vorhaus and his wife – who used to have late “picnic” lunches at their house in London – after the baseball games in Hyde Park. If I haven’t included the stories of other people in my book it is because I did not know them well enough to do so or that I did not think they would have liked me to include them.

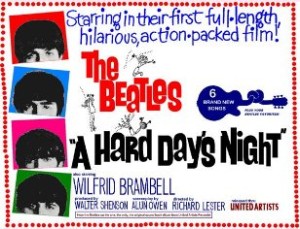

I confess I hadn’t known the name of Leon Becker, your second husband, who started out in the business as a sound man for Anthony Mann and who was blacklisted; but then, as you write about in the book, he had an amazing career overseas, ending up working with the Beatles.

Leon had many years of credits denied by the blacklist between Tony Mann and the Beatles. He was Wyler’s “ears” (Wyler’s quote) and “the man almost always by the director’s side” (so said Kirk Douglas) for four of Wyler’s films: Carrie (where his association with Olivier began – and was picked up in England years later with Bunny Lake is Missing), Detective Story, The Heiress, and Best Years of Our Lives. When Leon got to London he could not use his name, and Carl Foreman, who had just had his cleared, wanted to start up a production company and had no technical experience whatsoever. He pulled Leon in as a partner in Open Road Productions – for a percentage – where he could handle many of the actual details of making a movie – that Carl often wrote and produced and raised money for. Those films included The Key, The Guns of Navarone (which was a big money-maker), The Victors (a bomb), and Born Free (the script that Lester and I worked on). Carl and Leon broke up shortly after (Carl, incidentally, had just married Eve, Leon’s secretary for the previous two years), and then Leon teamed with Walter Shenson for The Mouse that Roared (a very big money maker and he had a good percentage), the two dreadful films I write about in the memoir, and THEN A Hard Day’s Night, in which I personally felt his brilliant musical knowledge managed to hold the film together. Whatever went wrong in our decade long marriage, I have never been able to dismiss the elephant in the room – the effect the McCarthy years had on each of us.

Leon had many years of credits denied by the blacklist between Tony Mann and the Beatles. He was Wyler’s “ears” (Wyler’s quote) and “the man almost always by the director’s side” (so said Kirk Douglas) for four of Wyler’s films: Carrie (where his association with Olivier began – and was picked up in England years later with Bunny Lake is Missing), Detective Story, The Heiress, and Best Years of Our Lives. When Leon got to London he could not use his name, and Carl Foreman, who had just had his cleared, wanted to start up a production company and had no technical experience whatsoever. He pulled Leon in as a partner in Open Road Productions – for a percentage – where he could handle many of the actual details of making a movie – that Carl often wrote and produced and raised money for. Those films included The Key, The Guns of Navarone (which was a big money-maker), The Victors (a bomb), and Born Free (the script that Lester and I worked on). Carl and Leon broke up shortly after (Carl, incidentally, had just married Eve, Leon’s secretary for the previous two years), and then Leon teamed with Walter Shenson for The Mouse that Roared (a very big money maker and he had a good percentage), the two dreadful films I write about in the memoir, and THEN A Hard Day’s Night, in which I personally felt his brilliant musical knowledge managed to hold the film together. Whatever went wrong in our decade long marriage, I have never been able to dismiss the elephant in the room – the effect the McCarthy years had on each of us.

I am struck by how hard you are on Carl Foreman in the book (for his deal with the Committee, but also for his personality and character), as compared to how conflicted or more understanding you are of Robert Rossen (who cooperated publicly with HUAC and behaved badly in his private life as well). Did you have a general feeling about informers that was sometimes mitigated by knowing the people under sympathetic circumstances?

Yes, I was hard on Carl. I believe he knew how I stood during the years that we were closely associated. I do not have a “general feeling” about informers. They are individuals as we all are with their own difficult history. They were as much victims as the rest of us. Not everyone possessed the steel it took to defy the Committee. Many were terrified of what their life would be if they did not give names. They made a choice, one that more often than not proved equally hard to live with.

Carl worked hard for his success and was not going to let go of it. I don’t criticize him for that. It is who he was. He was also bright, seemingly good-natured and talented. But he took advantage of those very people who had not had his sense of self-preservation. I don’t care to go into it. But I never was able to whitewash him in this matter. It did not change my feelings that other American producers abroad were also paying the blacklisted writers, etc., half the money that was paid to others, which helped bring in a picture on, or under, budget.

I can’t compare Carl with Bob Rossen. I never knew Carl as I did Bob. I was deeply disappointed in Bob for naming names, and he knew that I was. But, I could see that it ate him up, as it did not seem to do to Carl – at least that was evident to me. I lived in Bob’s home, his wife a good friend, his parents were like grandparents to me. He had deep feeling for his heritage and for his family. To my knowledge he never took advantage financially from those who had been blacklisted, and privately – as I knew him – he was never over the personal guilt he felt in giving names to HUAC. Some of what he felt might be gleaned from his films. Especially, Body and Soul (in my opinion one of the greatest boxing films), where Garfield climbs his way to becoming champ by devious methods, which causes the death of the one boxer who had been his friend.

I can’t compare Carl with Bob Rossen. I never knew Carl as I did Bob. I was deeply disappointed in Bob for naming names, and he knew that I was. But, I could see that it ate him up, as it did not seem to do to Carl – at least that was evident to me. I lived in Bob’s home, his wife a good friend, his parents were like grandparents to me. He had deep feeling for his heritage and for his family. To my knowledge he never took advantage financially from those who had been blacklisted, and privately – as I knew him – he was never over the personal guilt he felt in giving names to HUAC. Some of what he felt might be gleaned from his films. Especially, Body and Soul (in my opinion one of the greatest boxing films), where Garfield climbs his way to becoming champ by devious methods, which causes the death of the one boxer who had been his friend.

As Bob was a family member I knew him better than Carl – I knew his history. Perhaps it was hard to put things in their proper prospective but I do think I tried.

Was there a special character and personality to the London blacklist community, as compared to say the French one? Were there circles within the community? You don’t mention Chaplin or the many people associated with him that were blacklisted, and I notice you only give quick mention to some other well-known people like Joe Losey…

There was not a large blacklisted community in France for obvious reasons, even during earlier times. Few Hollywood writers/directors were fluent in French (the exceptions being Sidney Buchman, Jules Dassin and John Collier – who was English – but had spent time in Hollywood). There were some late-comers to the Riviera like myself who had lived in England who I had not previously known – but they did not form a “colony.” As it was 1970 by the time I lived there the blacklistees could have gone home if they had so wished and perhaps they had journeyed southward because the dollar (taxes) and the pound were high and at the moment the franc more welcoming; Europe now seeming, after so many years, more like home. Nonetheless, people did come (Paul Jarrico, Lester Cole) but like me, did not stay long. The Riviera – at least, where I was – could have been called a way-station during the late sixties and early seventies for the former Hollywoodites.

The expat community in France was not large enough for “circles.” It was quite different in the 50’s and early 60’s in London, when so many of us landed on English shores. Charlie Chaplin, although I recall he made A King in New York, there, otherwise seldom came to London, as he lived in Switzerland with his wife and numerous children. Joe Losey was not much of a “mingler.” I found him stand-offish and gloomy. I was friendly with one of his ex-wives (not a good report). I believe he nurtured his unique film style in England – pessimistic tales, obtusely lit, claustrophobic settings.

He never attended gatherings or the baseball games in Hyde Park. My husband Leon was somewhat friendly with him so there were a few social evenings.

There were many other Americans floating around London and Europe. European production was at its peak during the late fifties and sixties, and many American filmmakers had made an exodus abroad where stories could be shot for much less on “location.” European crews were less highly paid and with the favorable exchange of the dollar, a wave of talent was lured from Hollywood to England, Spain and Italy. They then came back to England to cut, splice, add music, dub etc. Most went back home after the film was ready for distribution. They seldom became a part of the expat community – which as I see it now – was pretty tight.

I see your book as a feminist statement, although you don’t really wave that word around. Was there a sisterhood in the blacklisted community?

I am a feminist. I admit it most proudly. I am also a great many other things. I think of myself more inclusively as a humanist and being a feminist is only one part of the equation.

The fact that there were few women working creatively behind and beyond the camera in Hollywood in the 1930s to the 1960’s gives a clear picture of how anti-feminist the industry was. Mostly, women were either actresses or they were script girls, secretaries or in the wardrobe department. There were a few women writers employed at studios – my friend Vera Caspary was one (blacklisted), Lenore Coffee, Isabel Lennart (she was called by HUAC and gave names), Marguerite Roberts, and Sonya Levien (who had problems but seemed to have survived in Hollywood. Her daughter Tammy Gold and her husband Lee Gold were part of our London group). Those are all I can think of. Studios bought a great many novels written by women and then had them adapted by men.

Although several actresses were blacklisted, I think Betsy Blair was the only one who came to England. So – no – there was not a sisterhood of female writers, etc. living as expats in London at that time. The women in the blacklisted community consisted mainly of the wives and daughters of the men. Perhaps, there was a sisterhood among them, but I was never a member. This was by my choice. I was a working mother of two children with little spare time for lunch meetings, shopping, etc. But they were always gracious in including me in some nighttime social events. I never felt any animosity toward me on their part. They were mostly a generation or more older than I. I can’t remember any of the wives I knew who worked. But then they might not have had access to what in the U.S. we call a “green card.” In the beginning I was sponsored by [producer] Raymond Stross (who brought me to England) and I was able to go in for renewals thereafter. But except for a time when I did some work for the BBC I was [always] employed by the foreign office of an American company under an assumed name.

Part of the book, your life story, takes place in Gstaad and Klosters. Were there many blacklistees living in those places? I was taken aback by your mention of Salka Viertel, Garbo’s friend and frequent scenarist, as being blacklisted. I had assumed she was “graylisted,” but as you knew her well this must be my ignorance. Such a great lady – and role model. Was she bitter?

I went to Gstaad after living in Klosters (where Salka lived). Neither town was really a gathering place for the Hollywood victims of HUAC. France, at least, had a film industry and studios. Klosters had drawn more literary types like Irwin Shaw and Peter Viertel (Salka’s son). Klosters drew many filmmakers there but mostly on visits – to see Salka, to ski. Salka was a handsome, wise, enchanting woman – always vital. People took strength from her. She was not American. Polish by birth, European by design. She was in her sixties and a concerned grandmother when she moved to Klosters – concerned about the welfare of her granddaughter – the child of her son, the writer, Peter Viertel. His wife, the child’s mother, had died in Switzerland in a tragic fire. Salka was a stable and wonderful influence on the young girl (the same age as my daughter).

Her advice was always sound and fair. She was never bitter. She could be sharp tongued if needed. She displayed no interest at all in returning to Hollywood (or the States). Her family was close at hand. People (famous, talented, old friends) just naturally traveled to see her (Garbo and Chaplin included). Visit Switzerland – see the Alps and Salka Viertel.

Gstaad was a complete opposite to Klosters. Yes, there was skiing and Julie Andrews (and Blake Edwards). Also, Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton and many more famous folk. Leon’s longtime friend (from childhood) Yehudi Menuhin, the great virtuoso violinist, lived there as well – and in the summer there were these wonderful concerts in a church nearby. The town was filled with celebrity and society. I would have preferred Klosters, but my daughter was graduated from the school she attended near there and was now enrolled in the American school near Gstaad to get American credits to use towards U.S. college entry. Nonetheless, I fell in love with Gstaad and even the marvelously dull Swiss and better yet, wrote well there.

There was a large expat community in Gstaad – but not my friends and colleagues from London. They came from all over the world and were there for reasons that would probably have fueled an entire studio’s story file. I found that fascinating. Gstaad was much more cosmopolitan than Klosters. It had fine, beautifully lit restaurants, serving their somewhat stodgy but delicious cuisine, a mountain top club, and the swank Palace Hotel. There was also a terrific international bookstore. It was also twice as expensive as Klosters (or at least was so at that time.) I had many friends visit me from the States – but except for Sidney [Buchman] – none that I can recall from my buddy expats.

The term “graylisted” gets bandied about. I would define it as “temporarily” or even “mistakenly” blacklisted for a short time, until the person comes to an understanding with HUAC or the studios. Do you agree? It never happens to a real blacklistee or former Communist, right?

You will not find the word “graylisted” or even “gray-listed” in the dictionary, and for good reason. If one was listed at all it meant that certain inalienable rights had been denied to you, and once you were on a “list” (given to the studios by HUAC or Red Channels, etc.) that was an immediate end to your freedom to work in your chosen field in the country where you were a citizen.

The American Heritage Dictionary writes (and I quote, as “blacklist” unlike “graylist” is an accepted word): “A list of persons or organizations that have incurred disapproval or suspicion or are to be boycotted or otherwise penalized.”

Once your name was on a list, that list was placed in HUAC’s hands to use on a to-call basis. The Committee could then draw from that list to order someone to appear before them as fit their current agenda, which generally was […] what bigger names could be gotten by bringing that person before them? Therefore, someone could be passed by if HUAC did not think they would be of strong service to them at that time. This did not mean that one’s name would come off the list. More often it remained “for further consideration.” Therefore, the person’s name remained on the “do not hire list” at the studios. To circumvent that, the victims used false names.

For about a year or two after Senator McCarthy’s death in 1957, there was a lull in the activities of HUAC and the lists were apparently revised. But HUAC came alive again in the early sixties. In my case I had since married Leon Becker, who had not only been blacklisted but who had given up his American citizenship to become a British subject. That rang bells. (See my letter from Leon in Leaving Home, page 184.)

I did not include in the book the difficult time we had earlier when he had accompanied me by plane from London to New York, and passport control refused to allow him to enter the country. Two guards marched him into a private area where I was not allowed to enter and then escorted him onto a flight taking off to London. By the time I was in the hospital (in LA a year or so later) he managed to get clearance to come to my side (medical emergency) on a limited visa. That was in 1969.

To end the discussion of “gray” or “black” – for most of the victims who finally were able to work in Hollywood again time had played a mean trick. The Hollywood they had known hardly existed. They had been gone years in most cases without legitimate credits, and unlike me they had not been able to write a best-seller [The Survivors (1967)] to take them on a new successful road.

I wrote that novel forty-seven years ago and by choice I have never sought screen work (or had to) since then, although Richard Zanuck and David Brown (who became my mentors) bought my first book and then engaged me to write a sequel (book form) of Gone With the Wind, which they planned to have adapted and film when the book was published. (That’s a long story – not for this interview).[2] Then somewhat later they twice tried to tempt me to try my hand at a screenplay, but both my heart and my head rejected the notion.

You are best known nowadays perhaps for your celebrity biographies. Was it hard or easier knowing some of the celebrities you have written about? I know your firsthand experiences with Judy Garland are written about extensively and poignantly in your memoir, but I am thinking also about people like Ronald Reagan, who is so central to the history of the blacklist (and to your biography career) but who doesn’t turn up in your memoir…

It is equally difficult for a biographer to write about someone they never met as one with whom they had a friendship – or perhaps quite the opposite. The subject’s celebrity or non-celebrity status has little influence. A serious biography (not an “as told to” etc.) usually takes about two years to write and often as long to research. (That figure does not include multi-volumed works like Robert A. Caro’s masterwork on LBJ, or Leon Edel’s on Henry James.) It depends a lot on whether the writer has an advance that covers at least some of the travel and secretarial, or research assistant costs. There were always expensive copying costs, photo research etc. and etc. Now, with the technical abilities of the modern computer, it’s easier and less costly.

If you do your job well before you have started to write, you have come to know your subject “personally” even if you have never met them. (Let’s face it – most biographies are about a person who is dead – and possibly has been for a long time.) I cannot imagine beginning to write about someone’s life without examining what I can of their life before I start. Something about that person has had to “speak” to you. There must be questions that need answers. You must feel (at least I must) that I have something to say about that person that has not been said before – at least coming from the viewpoint I may have.

Ronald Reagan had no role in my memoir because our lives had not really crossed at that time, and I was not yet writing biography. (We did have a curious connection. Many years later, when Early Reagan had been a success and I had returned to California and was embarking on a second book, The Reagans, taking him into the presidency, I did a large amount of my research at the Reagan Library here in Simi Valley. One day Nancy’s assistant came to tell me that Mrs. Reagan thought I might be interested in seeing something that was in the basement of the library. Of course I was. She led me down to this vast cave where all presidential gifts and memorabilia was kept and then across the space to a corner where a red-upholstered restaurant booth was placed. There was a note from Nancy that explained that she had bought the booth at the auction when Chasen’s [my uncle Dave Chasen’s famous restaurant] was closed, as she and Ronnie had sat in this booth when he had proposed to her and she had accepted.)

How hard was it to write this book? (Compared, say, to a novel or a Hollywood biography.) How did you research your own life? It’s a very intimate book; how did you make the decisions about how far you would go…?

There comes a time, and I am at that age, when you have to take your life in your arms and hold it to you to keep it breathing. So, no, it wasn’t hard writing the memoir. It was a necessity. Writing is a lifeline to me. I need it to breathe. Also, I felt I had a story that had not, and should be, told. There had been a great many books, films, TV documentaries dealing with the active years of HUAC showing the destruction wrought in the immediate wake of the hearings. But little was known of what happened in the years after HUAC to those men and women who had their lives so cruelly upended.

I wanted – needed would be a better word – to tell that story.

I knew it had to be a personal story, MY personal story – because that was the only way I could tell it.

It was important, I thought, to relate this in strong human terms. I was never really a political person, or an activist. I was a woman and writer who felt things deeply and who found my outlet in writing.

Yes, biography has been a frequent choice of mine in the past. But it requires tremendous travel, hundreds of interviews, and weeks – sometimes months – in dark, damp or humid archives, which I can no longer endure. Anyway I was driven to write Leaving Home as a memoir for the above reasons and because I believed I had a strong personal story that would connect with readers today.

Research, well… I have always kept a yearly journal or diary – many lost in transit – but I still have a shelf-full. I started doing this in my teens. I still make a special trip to the stationers in December to buy my journal for the coming years. Then – during the years in which Leaving Home, is set – people wrote letters – many letters! I saved an amazing number, which are quoted in the book. Best of all, my two children – who so closely shared those years with me – were there to consult whenever I was in doubt of when a particular event occurred, etc.

Yes, it is a very intimate book. Because it is my life and that did not give me leave to recuse myself from writing of incidents, emotions, affairs that I would uncover if I was writing a biography. Otherwise, how could the true person ever be understood?

How far should I go was always an important concern. I picked carefully through the experiences of my life – which ones to relate – which had any true bearing on the thrust of my life – at least these chronicled years as a single woman raising two children under difficult circumstances in countries not of our birth. We were the reverse of the immigrant family who comes to America. I kept to the main influences, the people who I knew had the strongest impact on my life. I don’t respect memoirs that drop names and ooze gossip that have no relevance to the personal story being told. Nor do I care to read about their sexual behavior behind their bedroom doors. I applied this same criteria to myself. I included who and what I felt (still feel) deeply about.

Nowadays you are living back in Hollywood, close to where you lived your formative years. Is there still a blacklisted community of any number that you stay in touch with? What message do you have for young people today who see the blacklist as ancient history? Why is it still relevant? What are its lingering effects on American film?

There are no longer enough victims of the blacklist alive to form a community in Los Angeles or anywhere else. I do occasionally hear from their children or grandchildren. I feel somehow like that old aged Indian in a long ago Western who, with much relish, tells stories of the days when the Indians (Native Americans) had to be cleansed from the land and how tough it had been for him to survive – but, here he was at 101 recounting his tale.

The thing that has settled deep in me is the lack of attention that has been paid to the McCarthy years in school history books, that America’s youth are mostly ignorant of those darkest of years. Relevant? Darn tootin! That was a time in America when freedom of speech, of the right to the pursuit of happiness, of justice under the law was almost lost. We need to be reminded that if power does get into the hands of those who live for power alone and can see no viewpoint other than their own, it could well happen again and perhaps be even more devastating.

Patrick McGilligan is a biographer, film historian and writer.

This is a great interview — I have always admired Patrick McGilligan’s work in film, particularly his excellent biography of Fritz Lang, The Nature of the Beast. As usual for Mr. McGilligan, this interview is detailed, perceptive, and beautifully framed — thanks for a fascinating peek into Ms. Edward’s life and work. More!