By Yun-hua Chen.

Showcasing restored films that are over 20 years old, the festival embraces the entire arc of cinematic history….”

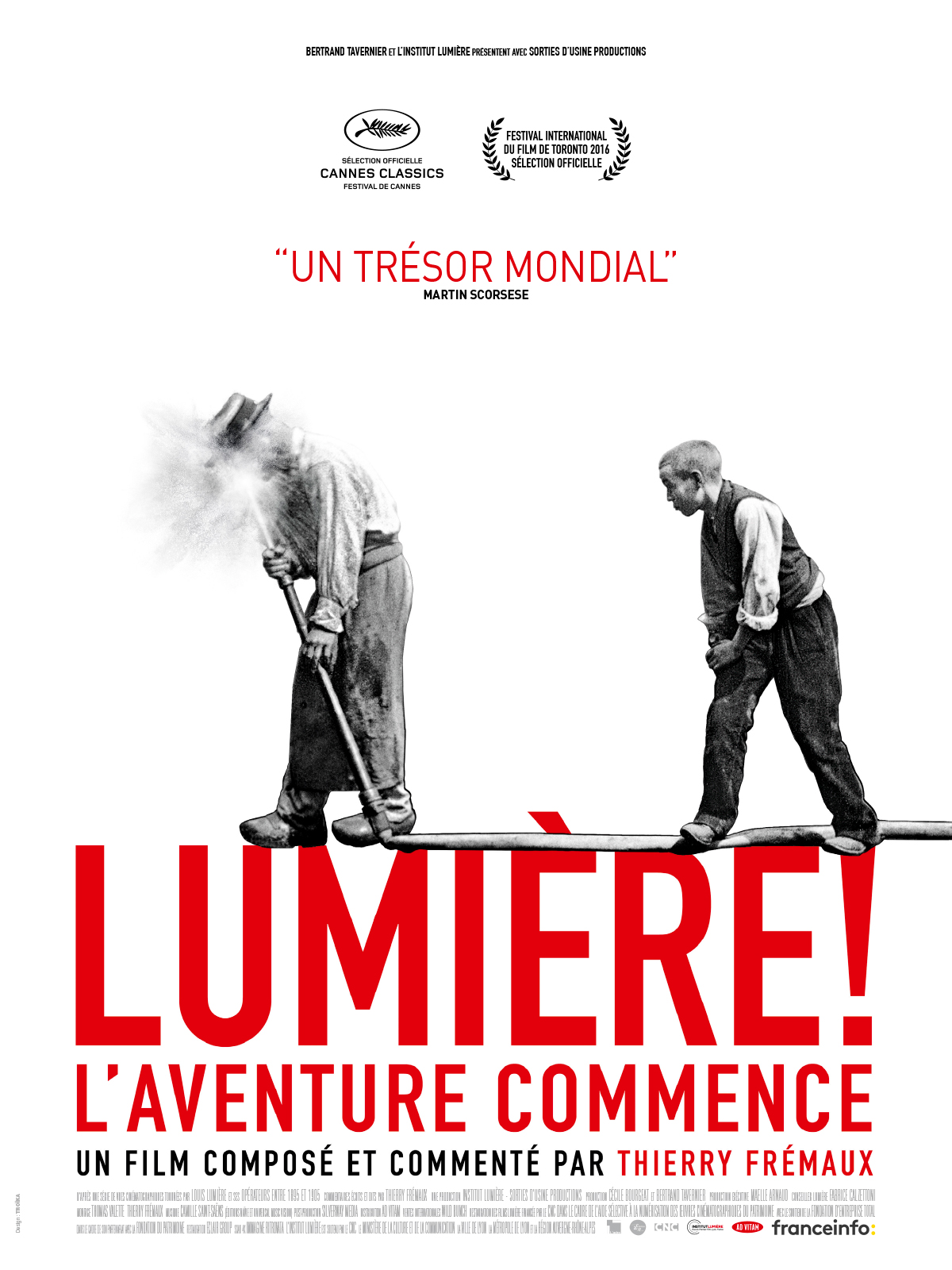

Now in its eighth year, the Budapest Classics Film Marathon showcases restored films that are over 20 years old. The festival embraces the entire arc of cinematic history—from the earliest moving images, such as those in Thierry Frémaux’s latest documentary Lumière, The Adventure Continues (2024), about the Lumière brothers who began making the first films in human history 130 years ago, to more recent classics like the opening film, István Szabó’s Being Julia (2004).

The very first public screening of a film—held in the Indian Salon of the Grand Café in Paris on 28 December 1895—included ten short films, among them the iconic Workers Leaving the Factory (1895), which marked the birth of cinema. As the medium enters its 130th year since the Lumière brothers’ first film, it is also 130 years since the founding of the French film company Gaumont and the birth of Oscar-winning Hungarian artist Marcel Vertès—both of whom are honoured in this year’s programme. The festival thus offers a sweeping historical reflection on cinema’s origins and evolution. As part of the Gaumont 130 programme, Subway (1985) was screened in one of the festival’s open-air showings, accompanied by The Samurai (1967), The Clever Girl (1956), and Flashdance (1983).

Being Julia (2004), partially filmed in Hungary, was a fitting choice for the festival’s opening gala. István Szabó, one of Hungary’s most celebrated directors, won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and the Best Screenplay Award at Cannes for his earlier film Mephisto (1981). His career spans six decades, and he is known for his interest in portraying the tension between individual choices and the currents of history—as we can see in his 20th-century European trilogy and, in this case, an actress’s inner struggle in the London theatre world of the 1930s. While the script may occasionally struggle to stand the test of time, Annette Bening’s performance is a breathtaking tour de force that makes the film convincing and enjoyable even from today’s perspective. She brings light, depth and empathy to a character who might otherwise be difficult to like, and every second of her presence is the heart and soul of the film. When rewatching it in the framework of the Budapest Classics Film Marathon, it was especially moving to hear a live orchestra perform the score—nowadays a rare experience—particularly in Budapest’s Urania cinema, a stunning Art Nouveau theatre from the 1890s, where early cinema was once enjoyed in the early 20th century.

Another jewel of the festival is Thierry Frémaux’s documentary essay Lumière! The Adventure Continues (2024; see top image), which presents a curated selection of films by the Lumière brothers. At the opening gala, he showed a series of Lumière shorts previously unseen and accompanied the screening with his live narration, translated on stage by the festival’s director Ráduly György. The Lumières are revealed to be far more than just Arrival of a Train (1896) or The Waterer Watered (1895); they created many more films featuring staged pranks, observational slices of life, and experiments with the camera as a new invention. This performative element of live narration also revives the spirit of early cinema. In Frémaux’s documentary, 120 short films—some rarely seen—are edited together and narrated by Frémaux himself; the film brings early cinema to life and serves as a well-curated overview of the Lumières’ work. Their unscripted documentaries, slapstick moments, and formal experiments in framing and editing all reveal the inventiveness and charm of these cinematic pioneers.

The festival also focused on several prominent individuals, including screenwriter Joe Eszterhas, directors David Cronenberg, Szabó István, and Atom Egoyan, as well as producer Robert Lantos, through masterclasses and roundtables. For Egoyan, three films were featured: his iconic Ararat (2002), The Sweet Hereafter (1997), and the more recent Remember (2015). Cronenberg’s Eastern Promises (2007), eXistenZ (1999), and Crash (1996) were shown, each accompanied by masterclasses.

In the programme “Ingrid and Roberto – Journey to Italy,” three collaborations between Ingrid Bergman and Roberto Rossellini were screened: Fear (1954), Journey to Italy (1954), and Stromboli (1950). Stromboli proved especially compelling when viewed with the distance of time. Bergman’s character, Karin—a tall, blonde Lithuanian woman—marries a local fisherman, Antonio, in order to escape from a prison camp after the war. The fishing community on the island of Stromboli is conservative, patriarchal, and closely tied to nature, while Karin is bourgeois and urban. The island’s volcanic eruptions bring with them heat, smoke and ash; the tuna hunt plays a vital role in the community’s survival. These natural and cultural tensions provide a dramatic backdrop for Rossellini’s neorealist exploration of alienation and resilience, which still feels poignant today.

Yun-hua Chen is an independent film scholar and critic and associate editor of Film International Online. Currently, she serves on the board of the German Film Critics Association.