By Roger Nygard.

We yearn to know the secrets of our mind, whether its power can lead to telekinesis or precognition. We yearn to know what lies beyond, from the world of ghosts to the world of alien life forms….”

–Gary D. Rhodes

I remember how Hammer Film’s Five Million Years to Earth (1967) and Gerry Anderson’s TV series UFO (1970) were must-watch events for me as a child, feeding my obsession with aliens and the unexplained. When a documentary called Chariots of the Gods came to movie theaters in 1970, I had to make a choice between seeing that or Beneath the Planet of the Apes. Not an easy decision! Later, when In Search of Noah’s Ark was released in 1976, it also competed for my movie-theater dollar with a larger-than-life remake of King Kong. I remember seeing wall-to-wall commercials promoting both these strange documentaries, making me think I absolutely must see them to learn their massive hidden “truths.” As a documentarian, I’m still completely obsessed with sci-fi (Trekkies), aliens (Six Days in Roswell), and the beyond (The Nature of Existence).

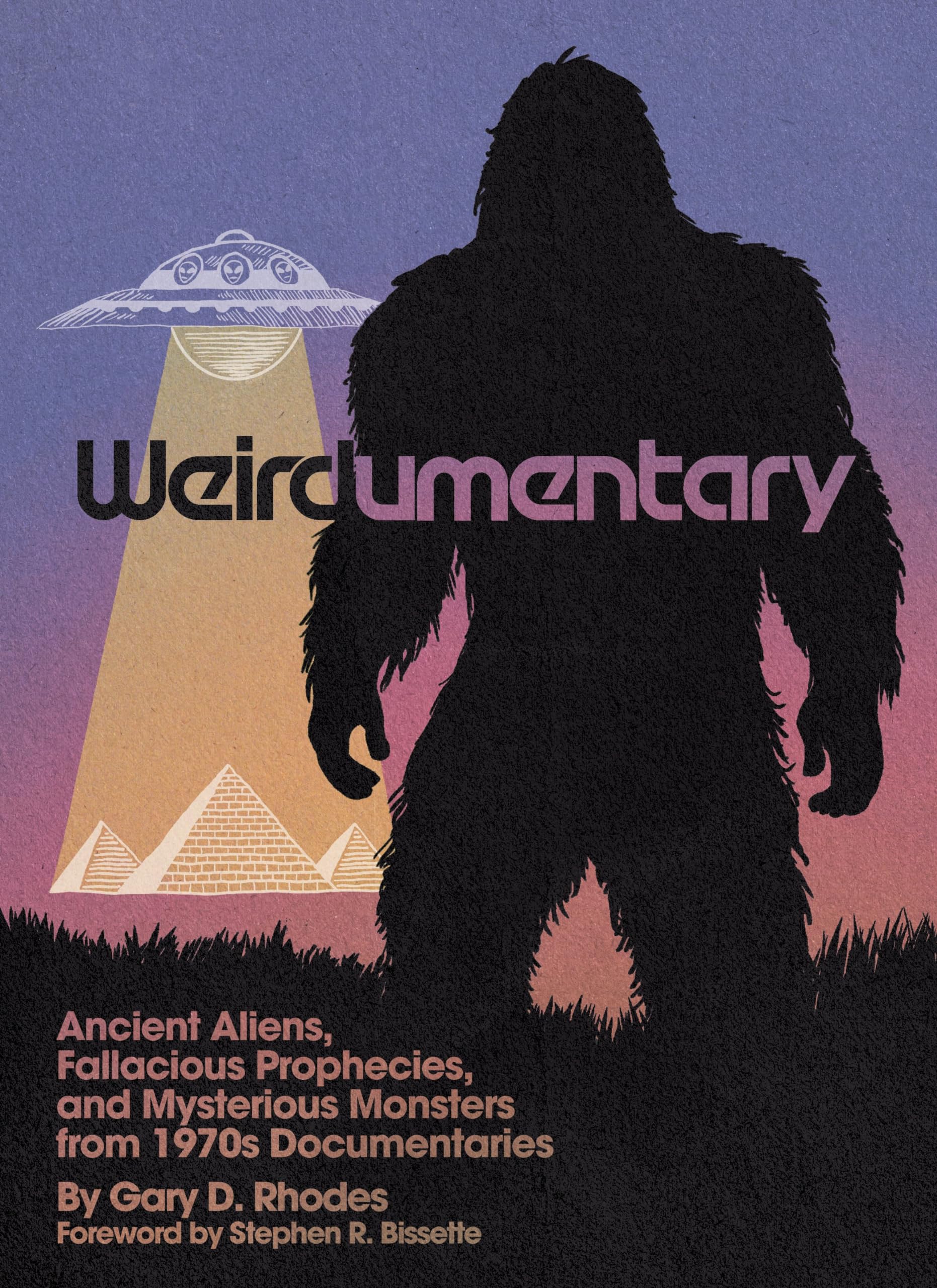

Now Gary D. Rhodes has written a meticulously-researched book called Weirdumentary (Feral House, 2025; Foreword By Stephen R. Bissette), which chronicles a history of the strangest offerings that ever came to local movie theaters. His book is as fun to read as these movies were to watch as a wide-eyed youngster seeking all things paranormal. But today I still have a few unanswered questions, so I put the screws to Dr. Rhodes.

Your book is fantastic. It brought back so many memories. Can you explain why you, and people generally, have always showed up for films like these odd documentaries?

I’m deeply grateful for your reaction to the book. I really wanted this to be a fun, nostalgic project, while also informative and lavishly illustrated, while also maintaining a scholarly foundation.

For me, I love these weird documentaries – which I have dubbed “Weirdumentaries” – largely because of the topics they cover. Most of us probably yearn to know secrets of our planet, what remains hidden, perhaps, deep in the ocean or in the forest or atop snow-capped mountains. We yearn to know the secrets of our mind, whether its power can lead to telekinesis or precognition. We yearn to know what lies beyond, from the world of ghosts to the world of alien life forms.

I fell in love with Weirdumentaries as a little kid during the seventies, seeing many of them at the movie theater and many on television. I was innocent and naïve at the time, but I think pop culture and American society was a bit naïve, at least to the degree that people, including many adults and even some scientists, were willing to probe for what might be. The questions – in our minds, and in these particular films – were in some respects more important than any answers that could be given to them. “What If?” … that’s powerful food for thought.

And I think these questions pervaded American culture of the twentieth century, from the works of Charles Fort to widespread interest in subjects like Spiritualism.

But for me, the Weirdumentary era really got going in 1968, on the heels of so much that was being discussed in America: UFO sightings, New Age religions, anti-materialism, reincarnation, holistic medicine, etc.

I specifically cite 1968 because that was the year that Erich von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods was published in English for the first time. And that year also meant the release of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). I don’t at all believe one influenced the other, but they feature similar stories, alien life forms visiting earth in earlier periods to help humankind.

Some people, ranging from the folks at the Catholic Legion of Decency to the individual viewer at the Cinerama theater on Sunset Blvd who ran screaming from what he saw, believed that God was at the end of the Stargate. Arthur C. Clarke’s novelization of the film made clear it was aliens.

And Kubrick, being as wonderfully opaque as he was insightful, suggested in an interview that aliens with such awesome powers might as well be gods to us, here on planet earth.

Watching a syndicated rerun of “The Zanti Misfits” episode of The Outer Limits scared the crap out of me when I was eight years old, and I was forever fascinated by aliens and monsters. What was a pivotal moment for you that captivated (or traumatized!) you with the subjects in the films you profile?

Seeing the Nazca Lines in Peru or mummies in Egypt, those kinds of images thrilled and captivated and scared me as a kid, because they were real. Whatever they signified, they are real artifacts and places. I suppose that was at lot like the old “based on a true story” tagline that horror films have used since the nickelodeon era.

But I was also scared by the power and watery depths of the Bermuda Triangle, and all the various pseudo-science explanations for it. And I loved the notion of visitors from other planets, because I was part of the original Star Wars (1977) crowd, seeing that flick at the age of five years old.

Of course I should add, importantly, that I really don’t believe in most of these subjects anymore. Now I love the Weirdumentaries from the standpoint of film history, and from cinema itself. Some of these films feature fascinating aesthetics … and extremely great soundtracks.

As a youngster, the latest editions of Ripley’s Believe It or Not! and Guinness World Records were always on my bookshelf next to Hardy Boys mysteries and Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine. How early did you immerse yourself in what later became research for the topics in Weirdumentary?

Certainly by the time of my earliest memories, meaning age three and four, I was deeply into horror and ghosts and paranormal subjects. By five, I was also in the thrall of science fiction.

I was a fan of Hardy Boy books and Scooby Doo cartoons. Ian Thorne’s books on classic horror cinema made an enormous impact on me as a kid. I remember vividly First Grade, when a classmate of mine held up Thorne’s book on Mad Scientists. And I couldn’t wait until he returned it to the school library so that I could check it out. (“Thorne” was of course a pseudonym, but none of us knew that till much later).

From there, well, it was so much. Movies on television, Famous Monsters of Filmland, etc. I became friends with Forry Ackerman as soon as I could, by the age of thirteen. Forry became my first literary agent. He was a gem. A major impact on my life in lots of ways. He and Bill Everson and Carroll Borland and, later, Robert Wise and Howard W. Koch. Robert Clarke and Joseph Turkel, too.

I always gravitated towards these people because of the films they made. I just got married in August, and guests included Donald F. Glut, Candace Hilligoss, and Bela Lugosi’s heirs.

If I am weird, I want to stay weird, always….

How were film producers able to turn audience interest in fantastic stories, oddities, and mysteries into these money-making enterprises? (Such as documentaries Mondo Cane, or Death: The Ultimate Mystery, etc.)

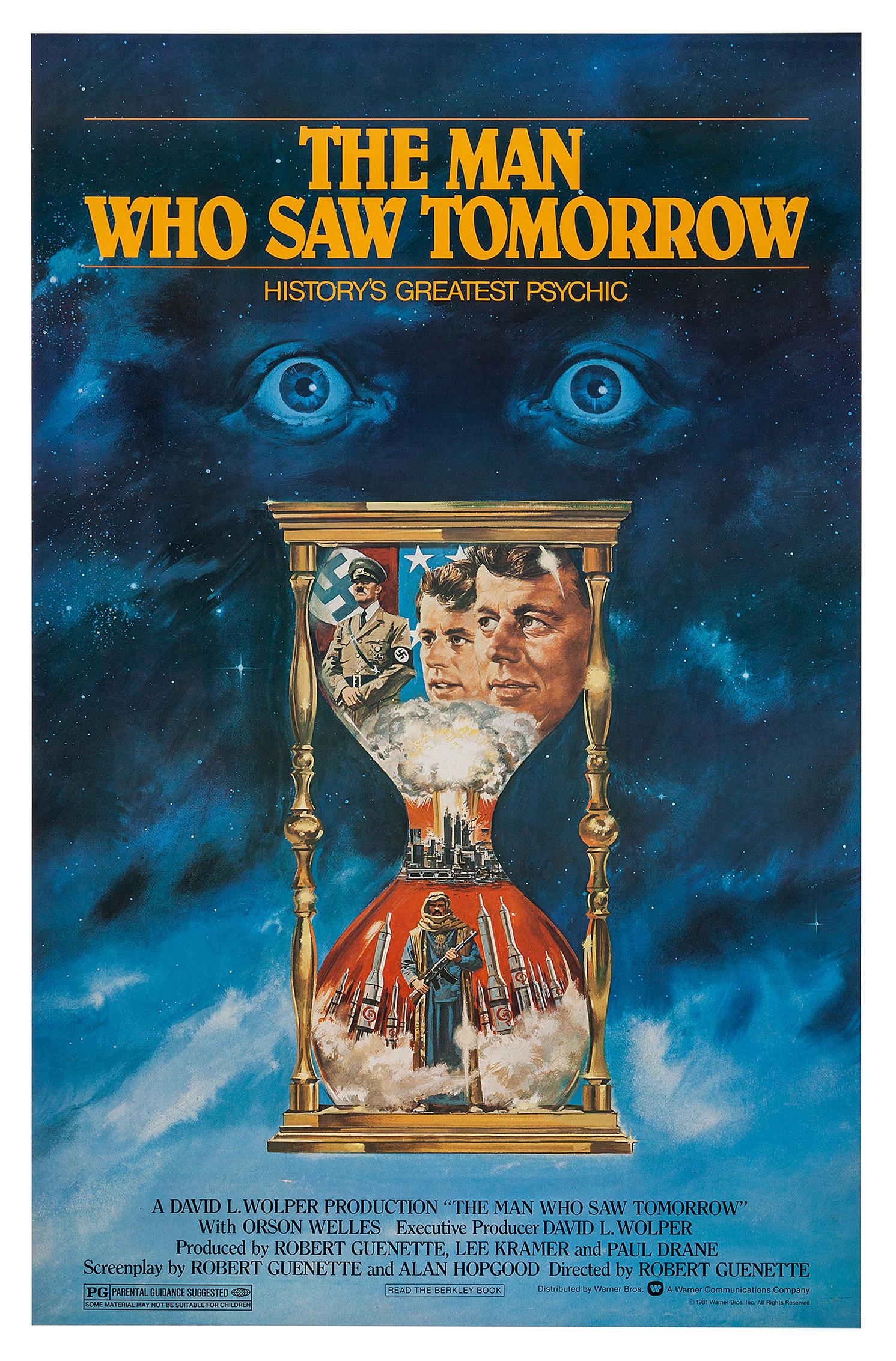

The Weirdumentaries that I cover were generally released between 1970 (with Chariots of the Gods) and continue through 1982 (with The Man Who Saw Tomorrow). Many of them had theatrical releases, something rare for feature-length documentaries at any point in American history.

Most Weirdumentaries featured three commonalities, which I attribute to their unique formula and its financial success.

The first was, no doubt, the film topics, for reasons we’ve chatted about. My book breaks them down into six categories: Ancient Aliens, UFOs, the Bermuda Triangle, Mysterious Monsters, Prophecies, and Speculative History.

The second Weirdumentary ingredient was the narrator, often an onscreen host, who was already famous for the weird, the strange, horror, science fiction, and so forth. Here I’m talking about Rod Serling, William Shatner, Leonard Nimoy, John Carradine, and of course Orson Welles, who became infamous after his 1938 War of the Worlds broadcast. Not all Weirdumentaries could afford that kind of talent, of course. Sunn Classic, my favorite film company behind these flicks, frequently used the great but lesser known Brad Crandall, for example.

The third common trait of Weirdumentaries became low-budget dramatizations of the events being described. We really saw that come to fruition in The Legend of Boggy Creek (1972). From there, recreations became a staple. Low-budget, yes, but still spooky when I was a kid.

You quote Leonard Nimoy in In Search of… asking in 1977, “Is there life after death?” How is fear of death a prime motivator behind many (or most?) of these weird documentaries?

Fascinating question! Death might be the prime motivator for all of these Weirdumentaries, either in the larger aspect of what our place in the universe is, whether our bodies can survive (as mummies), whether our creations can survive (as ancient texts and sculptures and architectural sites), whether someone out there cares about us (like ancient aliens or recent visitors), all of that, to whether we might possess dormant supernatural powers (like spoon-bending) or might exist after death. Here I’d invoke Stanley Kubrick again. He once suggested that even the scariest ghosts are a sign for us to be happy and optimistic, because if they’re real, they prove there is life after death.

I think these films remind me, and perhaps most of us, that the world of matter isn’t the only world that matters. Just because we can’t see something with our eyes, just because it can’t be proven scientifically, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have importance or, for that matter, that it doesn’t exist….”

You cover so many fascinating topics. Which one wears the crown—i.e., which topic are people most obsessed with: aliens, UFOs, the Bermuda Triangle, paranormal, monsters, speculative history, or prophecies?

Another great, but tough, question. Monsters scared me the most as a kid, probably. UFOs continue to fascinate me, especially given recent disclosures from the United States government etc. But life-after-death, selfishly, takes the number one spot. Ghosts, demons, near-death experiences: I’ve spent a fair bit of time thinking about those.

At the end of the day, I think these films remind me, and perhaps most of us, that the world of matter isn’t the only world that matters. Just because we can’t see something with our eyes, just because it can’t be proven scientifically, that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have importance or, for that matter, that it doesn’t exist.

Death is key to these films thematically. So too is faith. That’s a word that I believe scares many modern scholars, especially those working in the hard sciences. But that word is core to humankind, really, on a daily basis. And it certainly is important to Weirdumentaries.

Fortune tellers have always been able to pull money from the pockets of insecure folks wanting help making decisions. Was Nostradamus (or any of the psychics presented in these documentaries) ever right more often than a monkey throwing darts? (By the way, where is Nostradamus’s skull currently located? I too would like to drink from it so I too will inherit his prophetic powers.)

The prophecies of Nostradamus did spook me as a kid. But that was when I was a very, little kid. Of all the subjects covered in Weirdumentaries, I’d dismiss him the quickest. His extremely vague quatrains have no meaning of value, I believe. They are cryptic as to make them applicable to many situations. I don’t believe in them at all, but even if they were accurate (and they aren’t), but even if they were, what good would they do if they can only be attached to actual events after those events happen?

The same is true of some of the other Weirdumentary subjects. If someone could bend a spoon with their mind, I don’t know what that would mean other than unnecessarily ruined cutlery, certainly if all they can do is bend spoons, rather than anything more substantive.

How and why does human interest in sexual behavior, and weird examples of sex, thread throughout these films?

Sex is a part of these Weirdumentaries, but far less so than, say, to the Mondo movies of the sixties, which were aimed at adults. For the Weirdumentaries of the seventies, sex was at most implied. After all, a key aspect of those films was that they were G-rated, so that they could be viewed by the whole of the ticket-buying public, from as young as four to as old as 94.

What would you say is the craziest idea that any of these documentary producers ever presented?

I love it! There’s so much crazy it’s hard to choose. But one springs to my mind. Please allow me quote from my book, when I discuss the film World of Mystery (1979):

My own personal favorite … is a question about another faraway world: ‘What sort of life might exist here, in the volcanic sea-washed bosom of an emerging planet?’ The answer is obvious, of course. Rock people. And no, you aren’t stoned. [Narrator] Sidney Paul really does suggest there could be ‘Rock People.'”

What is the absolute most weird documentary you unearthed and why the hell was it ever made?

I’d have to go back to Harald Reinl’s Chariots of the Gods. Easy to forget now, but it was nominated for Best Documentary at the Academy Awards. It had an amazing soundtrack. It had everything to suggest it that was real, except for authentic proof, evidence, in the way that educated, mature adults can accept. Instead, it featured a wild and fast array of possibilities that, by the end of the film, were meant to lead us to a singular conclusion.

I think it was made to entertain, and that’s a beautiful thing. The Weirdumentaries were entertaining, that was their goal, and many of them are still fun.

In 1980 I watched William Shatner explore Hypnosis and Beyond on TV. I was inspired to buy an incredible 99-cent whirling hypno-coin from a Johnson Smith catalog to hypnotize my friends. Sadly, I was unable to get anybody to obey my devious commands. Which of these mysterious, bizarre documentaries gives all the answers I’ve searched for, with the certainty I have craved, since I was a movie-matinee-going child?

Mesmerism and hypnotism have such a longstanding grip on our collective imagination, including in the nineteenth century, as we see in Charcot, as we see in authors ranging from Edgar Allan Poe to Mark Twain. The sheer volume of early cinema films about hypnosis, and villains using it to their horrible advantage, in the wake of Svengali, was something I wrote about quite a bit in my book The Birth of the American Horror Film [Edinburgh UP, 2018].

It was so easy for Bugs Bunny to hypnotize Elmer Fudd. Not so easy for the rest of us. Which is why there isn’t really a single Weirdumentary that answers all our questions.

But this is why I cover also Alan Landsburg’s wonderful TV series In Search of… The ellipsis in its title, those enigmatic three dots, meant that the show chronicled all that is weird, sooner or later, over its six seasons.

The 1960s and 1970s were certainly a unique period for sci-fi and horror. My favorite three TV shows from that era were Time Tunnel, UFO, and Night Gallery. (And a special mention for Star Trek, discovered later in syndication.) What are your personal top three favorites from that era? Why did they affect you so much?

I loved the action of Star Trek (1966-69), which I saw in reruns in the seventies. I loved Battlestar Galactica (1978-79), which seemed attuned to the Weirdumentary culture, especially in its pseudo-science and pseudo-religious qualities. For the third, I’ve have to say the largely-forgotten series Cliffhangers (1979), which featured an episodic, vampire story called The Curse of Dracula. It is still worth viewing.

That’s all in addition to reruns of Bakshi’s Spider-Man cartoons (1967-1970), the spooky sleestaks of Land of the Lost (1974-76), and my beloved Web Woman (1977-1980).

That was an amazing era for television, new broadcasts and reruns.

Anything else you’d like to add about this exhaustive, engrossing, and megaweird book?

Thanks so kindly for your interest. It was a joy to write this book, as much as it was watching the films way back when. I really hope other readers discover or rediscover the same enjoyment.

Documentarian Roger Nygard is the author of Cut to the Monkey: A Hollywood Editor’s Behind-the-Scenes Secrets to Making Hit Comedies and The Documentarian: The Way to a Successful and Creative Professional Life in the Documentary Business.