By Gary M. Kramer and Michael Miller.

This year’s Tribeca Film Fest featured a handful of intriguing titles. Here is a rundown on a quartet of films that unspooled.

Handsome Harry (directed by Bette Gordon, 2009) is a terrific character study/road movie that never exceeds its modest expectations. Harry (Jamey Sheridan, who also produced) plays an ex-Navy man who gets a call from his dying buddy Thomas (Steve Buscemi). With one foot in the grave, Thomas claims he doesn’t want to go to hell. He asks Harry to help him seek absolution from David (Campbell Scott) for a  hazily remembered violent incident back in their Navy days. To fulfill his dying friend’s wish, Harry goes on the road and meets a handful of his ex-navy buddies – each with a different memory of the fateful events, and each with a different tragedy in their lives. Peter (John Savage) has wealth, but no love. His wife Judy (Mariann Mayberry, who gives a fantastic, scene stealing performance here) makes a pass at Harry, and eventually, she escape from her wretched life with Peter with him. Other episodes, involving Porter (Aidan Quinn) and Gebhardt (Titus Welliver) follow their own narrative arcs, with some minor surprises. What is a given, however, is who committed the crime against David – and why. Handsome Harry delays the obvious with a romantic subplot involving Muriel (Karen Young) a waitress smitten with Harry. Yet such moments are less a digression, than an opportunity for the talented ensemble cast to sink their teeth into their nicely etched characters. This film is an actor’s showcase first and foremost, and director Bette Gordon gives all the performers a chance to be tremendously expressive. She composes her shots well, too, providing visual cues about the characters and the emotions they feel. A final shot is particularly powerful. So, too is the film.

hazily remembered violent incident back in their Navy days. To fulfill his dying friend’s wish, Harry goes on the road and meets a handful of his ex-navy buddies – each with a different memory of the fateful events, and each with a different tragedy in their lives. Peter (John Savage) has wealth, but no love. His wife Judy (Mariann Mayberry, who gives a fantastic, scene stealing performance here) makes a pass at Harry, and eventually, she escape from her wretched life with Peter with him. Other episodes, involving Porter (Aidan Quinn) and Gebhardt (Titus Welliver) follow their own narrative arcs, with some minor surprises. What is a given, however, is who committed the crime against David – and why. Handsome Harry delays the obvious with a romantic subplot involving Muriel (Karen Young) a waitress smitten with Harry. Yet such moments are less a digression, than an opportunity for the talented ensemble cast to sink their teeth into their nicely etched characters. This film is an actor’s showcase first and foremost, and director Bette Gordon gives all the performers a chance to be tremendously expressive. She composes her shots well, too, providing visual cues about the characters and the emotions they feel. A final shot is particularly powerful. So, too is the film.

Lucía Puenzo, follows up her transgender teenager film XXY (2007) with Fish Child (El Niño Pez, 2009), a curious lesbian crime drama based on the director’s own novel. XXY’s phenomenal star, Inés Efron is Lala, the wealthy daughter of a judge whose life is threatened. Father and daughter have an uneasy relationship, but they do share one thing – Ailin (Mariela Vitale), the Paraguayan maid. Lala is in love with Ailin and they plan to run away together. This plan may also involve killing Lala’s father, but whether that happens or not is gradually teased out. Puenzo slowly has this soapy plot come into focus as the first part of Fish Child flashes back and forth in time, before the story is fully revealed. Such a deliberate narrative technique is good for establishing an intimacy among the characters – there is a great speech by Lala’s addict brother about how their father taught him not to trust anyone – but the dramatic payoff seems dissociated. The film’s tensest moment may be a scene in which Lala urges her father with a just a look to keep his hands off her girlfriend. The only sounds here are the crickets chirping, and it’s a chilling moment. When the story takes an interesting turn, it becomes full-fledged crime drama – complete with a gun in the glove compartment. Lala rescues Ailin in an act of love, but a previous scene has the lovers fighting. Will their romance survive? It almost doesn’t matter. Fish Child distinguishes itself by presenting the gritty underground networks of Argentine society. Even if the story is dumb or cliché, the atmosphere Puenzo creates keeps it interesting. A dream-like sequence in which Lala swims in the river and meets the “fish child” of the title is a hypnotic magical realist sequence, even if it borders on being silly. Alas, when the truth about the fish child is revealed, it’s gilding the lily. Puenzo still coaxes another fantastic performance from Efron. A scene of her distraught, cutting her hair is tremendous. Too bad Fish Child didn’t have more of these great moments.

Lucía Puenzo, follows up her transgender teenager film XXY (2007) with Fish Child (El Niño Pez, 2009), a curious lesbian crime drama based on the director’s own novel. XXY’s phenomenal star, Inés Efron is Lala, the wealthy daughter of a judge whose life is threatened. Father and daughter have an uneasy relationship, but they do share one thing – Ailin (Mariela Vitale), the Paraguayan maid. Lala is in love with Ailin and they plan to run away together. This plan may also involve killing Lala’s father, but whether that happens or not is gradually teased out. Puenzo slowly has this soapy plot come into focus as the first part of Fish Child flashes back and forth in time, before the story is fully revealed. Such a deliberate narrative technique is good for establishing an intimacy among the characters – there is a great speech by Lala’s addict brother about how their father taught him not to trust anyone – but the dramatic payoff seems dissociated. The film’s tensest moment may be a scene in which Lala urges her father with a just a look to keep his hands off her girlfriend. The only sounds here are the crickets chirping, and it’s a chilling moment. When the story takes an interesting turn, it becomes full-fledged crime drama – complete with a gun in the glove compartment. Lala rescues Ailin in an act of love, but a previous scene has the lovers fighting. Will their romance survive? It almost doesn’t matter. Fish Child distinguishes itself by presenting the gritty underground networks of Argentine society. Even if the story is dumb or cliché, the atmosphere Puenzo creates keeps it interesting. A dream-like sequence in which Lala swims in the river and meets the “fish child” of the title is a hypnotic magical realist sequence, even if it borders on being silly. Alas, when the truth about the fish child is revealed, it’s gilding the lily. Puenzo still coaxes another fantastic performance from Efron. A scene of her distraught, cutting her hair is tremendous. Too bad Fish Child didn’t have more of these great moments.

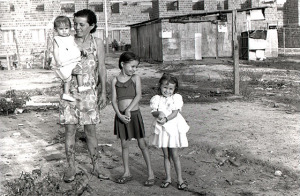

In Garapa (2009), Jose Padilha’s achingly sad documentary, gritty handheld black and white photography is used to tell the story of three poor families in Brazil. Garapa addresses how these people – all suffering from hunger and malnutrition – can’t survive on the government payoff of 50 Real a month. Their subsidies last for about 12 days if they use it for food. Many folks describe eating lunch or dinner in a given day, never both. (One 28 year-old father claims to never have had three meals in a day in his life). Entitled to milk deliveries, they can’t get milk during Carnival. And while some take advantage of the health care system, their lack of knowledge about condoms and sex education is about as effective – and as frustrating – as the belief one man repeats that “God will provide.” Garapa certainly rubs the viewer’s nose in the desperation of each family’s situation. Lengthy sequences show the children eating a mush of rice and beans, made with beans so hard “you can load a gun with them,” one mother says. The children, naked, or almost so, run around the bleak landscape, or roll around the floor that also functions as the family toilet. Flies cover children’s faces and bodies. Beds are wet mattresses and full of ants. The door to one woman’s apartment is “locked” by being tied up with a bra (her husband sold the door). Padilha studies his subjects carefully, unflinchingly, recounting these horrors in as much as disbelief while he urges people to pay attention. A question can be asked if he is exploiting his subjects, but one could also suggest he is making a call to action. Regardless, the film has an overwhelming effect. The title, Garapa, comes from the name of the sugar/water mixture that kids are fed to sustain them. But it also undernourishes, and even harms them. When a child gets a toothache (probably from being fed so much sugar water), it goes untreated. Padilha gives the kid an aspirin offscreen, which temporarily resolves the problem, but the boy’s father denies the toothache will recur. Such moments are heartbreaking, and even numbing. Likewise, the sound of children crying from hunger is constant, and unsettling. Nevertheless, the pride of these people – they will gladly accept alms, but won’t go begging – comes through. These families are practically determined to eke out a life. And viewers who see this remarkable film and feel paralyzed to do anything about the situation, can only hope that these families and the many others like them will somehow manage to survive.

In Garapa (2009), Jose Padilha’s achingly sad documentary, gritty handheld black and white photography is used to tell the story of three poor families in Brazil. Garapa addresses how these people – all suffering from hunger and malnutrition – can’t survive on the government payoff of 50 Real a month. Their subsidies last for about 12 days if they use it for food. Many folks describe eating lunch or dinner in a given day, never both. (One 28 year-old father claims to never have had three meals in a day in his life). Entitled to milk deliveries, they can’t get milk during Carnival. And while some take advantage of the health care system, their lack of knowledge about condoms and sex education is about as effective – and as frustrating – as the belief one man repeats that “God will provide.” Garapa certainly rubs the viewer’s nose in the desperation of each family’s situation. Lengthy sequences show the children eating a mush of rice and beans, made with beans so hard “you can load a gun with them,” one mother says. The children, naked, or almost so, run around the bleak landscape, or roll around the floor that also functions as the family toilet. Flies cover children’s faces and bodies. Beds are wet mattresses and full of ants. The door to one woman’s apartment is “locked” by being tied up with a bra (her husband sold the door). Padilha studies his subjects carefully, unflinchingly, recounting these horrors in as much as disbelief while he urges people to pay attention. A question can be asked if he is exploiting his subjects, but one could also suggest he is making a call to action. Regardless, the film has an overwhelming effect. The title, Garapa, comes from the name of the sugar/water mixture that kids are fed to sustain them. But it also undernourishes, and even harms them. When a child gets a toothache (probably from being fed so much sugar water), it goes untreated. Padilha gives the kid an aspirin offscreen, which temporarily resolves the problem, but the boy’s father denies the toothache will recur. Such moments are heartbreaking, and even numbing. Likewise, the sound of children crying from hunger is constant, and unsettling. Nevertheless, the pride of these people – they will gladly accept alms, but won’t go begging – comes through. These families are practically determined to eke out a life. And viewers who see this remarkable film and feel paralyzed to do anything about the situation, can only hope that these families and the many others like them will somehow manage to survive.

One of the hotter tickets at this year’s Tribeca Film Festival was American Casino (directed by Leslie Cockburn, 2009). This incisive documentary unwinds the sub-prime mortgage fiasco, its genesis and the affects it has on a number of families profiled in the film.

One of the hotter tickets at this year’s Tribeca Film Festival was American Casino (directed by Leslie Cockburn, 2009). This incisive documentary unwinds the sub-prime mortgage fiasco, its genesis and the affects it has on a number of families profiled in the film.

American Casino begins by making the point that the securitization of mortgage debt – the bundling of mortgages into bonds and selling them to investors – essentially off-loaded the risk that mortgage lenders had traditionally carried themselves. In some respects this was a good thing; more money became available for borrowers. However, lenders would take their profit off the top in the form of fees for placing the mortgage and bundling the debt. The film clearly shows how this fee income was very lucrative and had little risk. The unintended consequence of this model is that it created an ever-increasing demand for more mortgages from which the lenders would extract these fees. This ravenous appetite for more and more mortgage loans is a primary source of the troubles facing the industry and their customers today.

American Casino adroitly looks at the current crisis from a number of vantage points. All along the transaction chain are individuals – some identified, others not, (such as an anonymous Bear-Stearns executive) – who had the sense that these deals were trouble. The film also humanizes the issue by presenting three families in Baltimore – all at some stage of losing their homes to foreclosure. Cockburn not only explores the impact on the economy as a whole, but also the impact on people and neighborhoods. For example, abandoned homes attract squatters and crime, while derelict properties attract mosquitoes and vermin; the mortgage crisis has become a public safety and public health issue. Cockburn makes these seemingly unrelated circumstance resonate. Furthermore, she drives home the point that a disproportionate percentage of these sub-prime loans were issued to African American households.

Cockburn’s purpose in making American Casino is to show how folks like Denzel Mitchell, one of the African Americas interviewed, is a “chip” in a giant game of chance. She reveals that lax procedures, poor documentation and underwriting and outright fraud on the part of some mortgage brokers resulted in people being saddled with loans that were extremely difficult to pay. Individuals like Mitchell were enticed into loans that their incomes could not support. As people fell behind on their loans, the foreclosure process begins and losses on the bonds mounted. Furthermore, as the film shows, these events reflected the true level of risk, and investors started cashing out.

Cockburn’s purpose in making American Casino is to show how folks like Denzel Mitchell, one of the African Americas interviewed, is a “chip” in a giant game of chance. She reveals that lax procedures, poor documentation and underwriting and outright fraud on the part of some mortgage brokers resulted in people being saddled with loans that were extremely difficult to pay. Individuals like Mitchell were enticed into loans that their incomes could not support. As people fell behind on their loans, the foreclosure process begins and losses on the bonds mounted. Furthermore, as the film shows, these events reflected the true level of risk, and investors started cashing out.

Cockburn makes this complex set of facts extremely compelling. Looking at the motivations that drove this economic fiasco helps identify the issues regulators should study most closely. While many of the details in this film have been reported in the mainstream media, American Casino does the best job thus far of connecting the disparate data points into a cohesive narrative.

Following the screening, there was a stimulating panel discussion conducted by Alex Blumberg from National Public Radio that included director Cockburn, her husband Andrew Cockburn who co-wrote and co-produced the documentary, Mark Pittman a reporter from Bloomberg News who is featured in the film, and noted NYU economist Nouriel Roubini. The audience included New York State Superintendent of Insurance Eric Dinallo, and Superintendent of Banking Richard Neiman, both of whom participated in the discussion.

Gary M. Kramer is the author of Independent Queer Cinema: Reviews and Interviews, and co-editor of the forthcoming Directory of World Cinema: Argentina.

Michael Miller is an independent scholar who frequently reviews documentaries for Film International’s “Around the Circuit” column.